LAS VEGAS, NV – “Dry for Decades,” the tourist placard at Hoover Dam’s Nevada spillway says. “The last time the waters of the Colorado River flowed through this spillway was in 1983.”

LAS VEGAS, NV – “Dry for Decades,” the tourist placard at Hoover Dam’s Nevada spillway says. “The last time the waters of the Colorado River flowed through this spillway was in 1983.”

On my way to this year’s annual meeting of the Colorado River Water Users Association, I spent some time yesterday at Hoover Dam and Lake Mead, the great reservoir that stores water for Las Vegas, central Arizona, Southern California, and Mexico.

The reservoir was at elevation 1,081.5 feet above sea level, which in another time would have set off alarm bells in the water management community. But in the years since 2010, when Mead first dropped into alarm bell territory, the sound of the warnings has become muted. In 2010, Mead in the low 1,080’s felt dire. But in the years since, for better or worse, the river management community has become accustomed to operating under the constraints of low reservoirs.

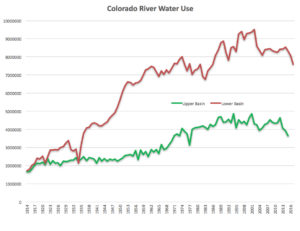

Colorado River water use, data USBR, graph by John Fleck, University of New Mexico Water Resources Program

The “for better” part of this is the increasingly sophisticated operations skill set, the juggling of levels between the various reservoirs on the Colorado River to keep the system operating, and the remarkable conservation success, especially in the Lower Basin, that has stabilized Mead’s levels in the 1,070’s to 1,080’s, at least for now. The latter is remarkable. Lower Basin use of Colorado River water – in Arizona, Nevada, and California – is on track to end the calendar year at 6.7 million acre feet, its lowest since 1986.

The “for worse” part of becoming accustomed to Lake Mead’s bathtub ring and the math that goes with it is the waning sense of urgency.

Policy happens in the hallways at CRWUA, which in this case was a striking conversation outside the elevators last night at Caesar’s Palace as a clog of basin water managers formed on their way to dinner, blocking the hallway so that every new water manager who walked past had no choice but to stop and join the conversation. I’m not a journalist any more, so I’ll happily leave the details unsaid – folks need space to work this stuff out, and I’m confident that they’re trying. But in general, the conversation included two key elements. The first was an enumeration of the various stumbling blocks in the way of a new Drought Contingency Plan, the almost-but-not-quite-done scheme to rejigger Colorado River water allocation and management in times of shortage. The basic terms of the deal have been set for two years, but there are a lot of niggling details.

Folks were very close a year ago at CRWUA to signing the deal. But then we had a reasonably wet winter, the big reservoirs rose a bit, and the pressure was off.

In the classic Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, the political scientist John Kingdon describes how policy entrepreneurs work and refine their ideas, awaiting the convergence of problems and politics to open a window of opportunity. One example of how that might happen is when the problem gets bad enough – say, for example, a plummeting reservoir – that the issue rises onto the action agenda.

So it is not surprising that one of the questions that came up in the Caesar’s Palace hallway, outside the Palace Tower elevators, was the question of what would happen if we had a bad snowpack this winter. At that point, a Kingdon-style “policy window” will likely open. You could think of CRWUA as a gathering of the policy entrepreneurs, preparing for that moment.

Lake Mead is currently 39 percent full (or 61 percent empty, as one wag said in reply when I tweeted about this yesterday). Interesting to ponder what the trigger point is for action.

What if there were a biolgical agent that could rapidly construct and maintain 10,0000s of micro-reservoirs and maintain each dam for no cost, be enviromentally compatible with the intermountain ecosystem and mitigate the effects of flash flooding? Oh, wait, there is…….Castor canadensis, the North American beaver.