Some evenings I curl up with a laptop and cruise Calisphere’s orange create label collection. Absent some years away for college, I spent the first three decades of my life in Southern California’s “citrus belt”, that source of the region’s wealth and culture reaching east from Pasadena across the foothills of the San Gabriels to Riverside, Redlands, and most importantly San Bernardino, the city of my mother’s birth. I’ve now lived in Albuquerque more years than I lived in Southern California, but the place made me, though I’m only now, distanced by the second half of my life, coming to understand it.

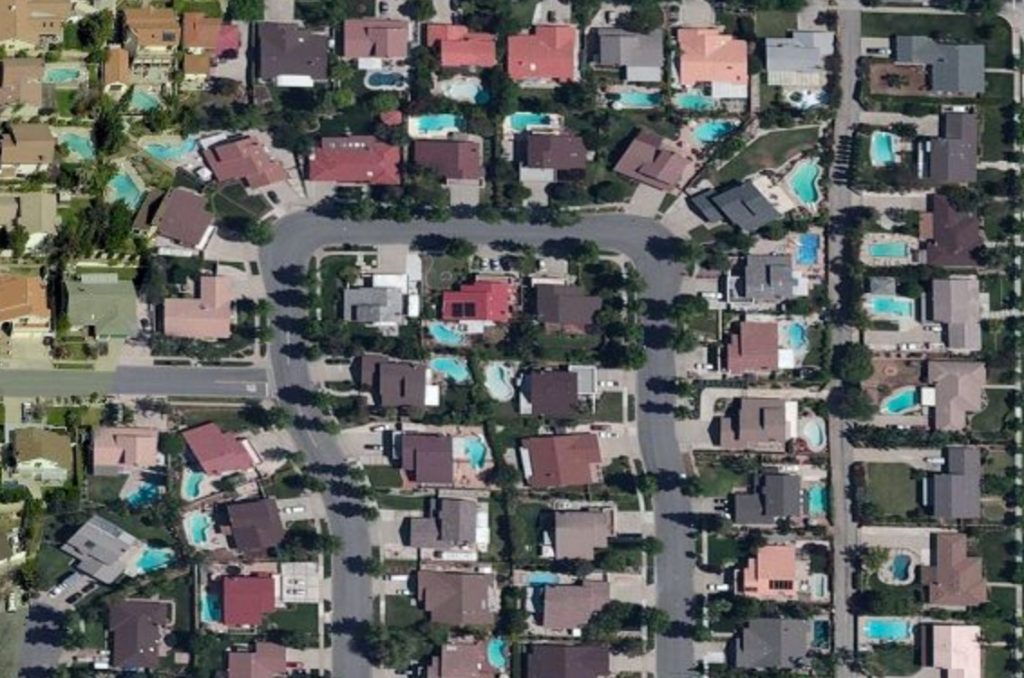

When you’re a kid you don’t think about this stuff, you just hang out at the pool and cut through the groves on romps around the neighborhood.

So now, I stare at orange crate labels.

I grew up in Upland, one of the early irrigation colonies that transformed climate, mountain-front runoff (ground and surface) and eastern capital into citrus wealth in a tidy, organized community I never fully understood while I was in it.

In the backyard of my childhood home was a small concrete pipe, emerging vertically from the ground, capped, with simple metal valves.

By the time we lived there the pipe was dry. Once, it brought water to the citrus grove that was the ancestor of our neighborhood in the Upland foothills – “San Antonio Heights”. Concrete feeder pipe beneath the groves held water under modest pressure. Larger standpipes known as “gate stands” spaced along the line held valves that, when turned, would release the water to the outlets like the one in my backyard. My sister, Lisa, remembers the gate stands in the groves still operating down the hill from our house, remembers wanting to turn them, but they were always locked.

Water leaves traces in this way, on our landscape and in our lives. Many of these traces are obvious – the alluvial fan on which our home and the groves before it were built, sands and gravels and cobbles eroded by Southern California’s big winter storms, splaying out from the San Gabriel Mountains. Some are less so – the hidden pipe beneath our backyard and the landscape it helped create.

Our backyard still had a few of the old citrus trees. Our next-door neighbor repurposed the water supply to a suburban pool. My dad was an artist, drawn to Southern California in the years after the Second World War, part of a wave of creative energy drawn by a culture of art and freedom that the newcomers then remade. Our neighbor, with the pool, was a union steelworker. His adult stepson was a member of the Klu Klux Klan. Southern California defies easy explanation.

Dad and our neighbor built steps over the low back wall, and summers were spent either in that pool or the others maintained by the families of my childhood chums. This must surely have been paradise, that “reasonable facsimile of Eden”, to quote Reyner Banham, that comes with pouring water on desert land.

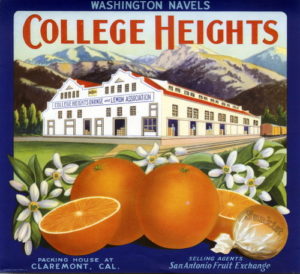

After returning from the diaspora of college, I began my career as a professional writer at a small newspaper in the town of Claremont, next to Upland. The College Heights packing house, seen in the orange crate label above, was a few blocks from the newspaper where I worked, a vacant relic of the community’s citrus past. Today it “is the largest historic building in the Claremont Village and one of its hottest attractions. A century of architecture comes alive with fine dining, jazz concerts, stand up comedy, hip boutiques, wine tastings, art classes, art walks and festivals.”

The web page is decorated with pictures of lemons.

When I was beginning my writing career in Claremont, I bought a nice typewriter and rented an upstairs room in the Arbol Verde neighborhood on the east edge of town, the old “barrio” that was at the heart of the area’s segregated and deeply racist agricultural labor structure. It was my Eden’s original sin, its purpose lost with the decline of citrus, turned into a neighborhood where a self-consciously poor young writer could afford a room.

Climate, soil, and water defined the geography of the citrus belt – climate because it had to be above the valley freezes that were death to the fruit, soil and water because the well-drained alluvium was perfect for irrigation with the water from the mountains above, either surface or groundwater. I had no idea then it was such a special place, it simply was, but I know now that it combined eastern capital and racist labor with the geography’s bounty to create the solid American affluence into which I was born.

Carey McWilliams (a radical to whom I was not exposed in the sanitized history of my childhood) wrote in 1946 of his “apprehension that all is not well, that some vital quality of the land has been subverted”:

The incessant pumping of underground waters, and the ever-expanding demand for water in large urban centers, makes one wonder just how real and enduring are these beautiful groves.

McWilliams’, in his Southern California Country: An Island on the Land, offers up a grim conclusion about the sustainability of the enterprise:

Puzzling over the same question, a character in Howard Baker’s novel concluded that “the people were powerless to change the desert very much,” over the long reach of the years.

I’m more optimistic than McWilliams about our post-desert trajectories, but the groves that spread south in the 1970s from my childhood home are gone. Note the pools.

A really fine personal essay!

I live in southern Cochise County, AZ, just a few miles from Sonora, and thus I’m not in the Colorado River drainage — all of our valley’s excess water flows into the Yaqui River. Nevertheless, I enjoy your water writings!

Dear John,

I enjoyed this post! I was also raised in Southern California… You probably knew, engineer George Chaffey founded Ontario and Ediwanda as irrigation colonies, which he followed with the irrigaition system in Imp Valley.

I really liked your book Water’s For Fighting Over, and perhaps these posts inspired by Banham et c. may lead to another project?

Saludos!