KAWUNEECHE VALLEY – The Colorado River was flowing this morning at around 700 cubic feet per second at the USGS gauge near Baker Gulch. It felt like a lot of water – spilling the channel banks and out into the meadows, as is its way in a good spring runoff.

Rocky Mountain National Park near the headwaters of the Colorado River. The scar on the hillside is the Grand Ditch.

If you look downstream at the Colorad0 by the time the river passes Glenwood Springs, the contribution of the little tributary through the Kawuneeche Valley seems tiny – around 5 percent of the 14,000-plus cfs right now at the Glenwood gauge. But by virtue of geographical naming conventions, the “little tributary through the Kawuneeche Valley” is named “the Colorado River”, so that’s where I came to make a headwaters pilgrimage.

I’m between Colorado meetings. Thursday and Friday was the Martz Conference at the University of Colorado School of Law, a gathering of the Colorado River brain trust I try to attend every year. Next week the University Council on Water Resources is converging on Fort Collins. For the few days between, I’ve fled across the continental divide to Colorado’s West Slope to get some work done, and to do my favorite thing – wander around looking at water stuff.

One of the hardest things about mastering the nuances of Colorado River Basin water policy and politics is the nuance of intra-state conflict. I mostly work at the basin scale, where it’s easy to fall into the trap of viewing each state as a monolith, as a single blob of shared interest. At best they behave that way when it comes to working in the basin-scale governance process, but back home it’s always more complex.

Here in Colorado, the important nuance is the West Slope-Front Range tension over trans-mountain diversions – moving water from the west side of the continental divide to the east. The “Grand Ditch” (so named because the Colorado was then named the Grand River here) is one of the earliest large such diversions, built in the 1890s to take water from what is now the Never Summer Mountains and deliver it by gravity flow across La Poudre Pass for farmers on Colorado’s east side.

That gash across the mountainside in the picture above is the Grand Ditch.

With all due respect to my friends at Northern Water, the plumbing up here is absolutely crazy.

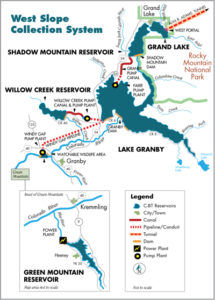

The Colorado here flows into Grand Lake, which they expanded with the construction of Shadow Mountain Dam. They drilled a tunnel out of the bottom of Grand Lake, under Rocky Mountain National Park and the continental divide, to deliver water to Northern’s system.

But wait. There’s more. Just downstream of Shadow Mountain is Lake Granby, created by the construction in the 1940s of Granby Dam. Grand/Shadow Mountain don’t have a lot of storage, so they built Granby to add to the system’s storage capacity. But Granby is downstream of Grand Lake and the tunnel. So water is pumped back upstream when it’s needed.

But wait. There’s more. Downstream from that is Windy Gap Reservoir. Which expands the storage a bit more. When it’s needed, Windy Gap’s water is pumped back uphill to Granby. But if Granby is full? See Windy Gap Firming Project.

But wait. There’s more. Green Mountain Reservoir is my favorite piece of this crazy system, because it illustrates the complex institutional tensions that arose when folks on the east side of continental divide began increasing their trans-mountain diversions. Green Mountain is a sort of compensation for lost water. It provides storage of early runoff to keep Colorado River flows above Kremmling higher during the summer months when the river would otherwise drop because of the diversions from all the plumbing upstream. Added storage for West Slope use was part of the grand compromise for the trans-mountain diversions folks east of the continental divide wanted.

Click on the embedded map for a link to a high-res pdf of the rest of the system, courtesy of Northern Water. Because yes, there’s more.

All of this storage and tunneling and pumping is based on the idea that during the peak of spring and summer runoff, there’s lots of water. Stored and then moved to other places, it provides benefits. But it also is worth noting that were it not stored, pumped, tunneled, diverted, it would flow downstream where both human users and natural systems (“rivers”) await. Hence the importance of understanding the nuances.

The argument in Colorado has always been between those who viewed the economic potential and therefore the value of the water as being far greater along the Fort Collins to Pueblo “Front Range” corridor, versus folks on the west side who so keeping that water as central to their communities’ future. On the West Slope water is, to borrow from the historian Steven Schulte, “as precious as blood“.

the Colorado River