As the new “water year” begins, we’ve got some challenges in the Colorado River Basin.

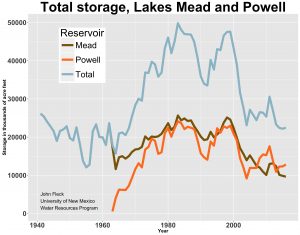

It is worth noting some good news – despite a mediocre runoff year at 88 percent of average, storage in the basin’s two huge reservoirs, Mead and Powell, is almost exactly the same as it was last year at this time. (source pdf)

total storage, Mead and Powell

Lake Powell ended September with a surface elevation of 3,611 feet above sea level, five feet above last year. Lake Mead ended at 1,075, three feet below last year.

But it’s taken a lot of institutional duct tape to hold things together at those levels, and duct tape is not sustainable.

The current rules for allocating Colorado River water aren’t working. They allow farms and cities in Arizona, Nevada, California, Baja, and Sonora to take out more water than flows into the reservoir each year. Over short time scales in a variable system, that might make sense. The point of a big reservoir is to store water in wet years for use in dry years. But if there’s an imbalance in the long run, if we keep taking out more year after year, eventually we’re screwed unless the rules adjust as the reservoir drops.

Our current rules don’t.

I had a great pair of conversations over the last week with Ian James at the Desert Sun, who’s been doing some really thoughtful work about water use in the West (and around the world). He was kind enough to transcribe them to share with his readers some of my take on the Colorado River and why, despite its troubles, I am optimistic. This bit stuck out, when Ian asked about my assertion that “we need new rules” to govern the allocation of Colorado River water:

Clearly the rules are going to be that everybody, all of the three states in the Lower Basin, are going to be taking less water out of Lake Mead as Lake Mead drops. But how much less and how you allocate the details of those shortages, those have to emerge from the negotiations among California and Arizona and Nevada and the federal government and Mexico, and that’s the really important thing that I learned about how these negotiating processes work.

This seems like a no brainer – take less water out of Lake Mead! – but the details are hard. As I’ve been arguing over and over again in the interviews I’ve been doing to accompany the release of my book, communities in the West have shown repeated success in using less water when they have to. But no one wants to volunteer to be the one to use less, let those other people over there do it.

The “drought contingency plan” now under negotiation appears to have a good shot at fixing this problem. It’s a new set of rules to take less water out of Lake Mead, and by construction it would stabilize Mead’s levels as users agree to deeper and deeper cuts as needed until, at low lake levels, inflow and outflow would equalize. This is in everybody’s interest, but it is a classic collective action problem which is running headlong into what I view as the essential hurdle. State-to-state negotiators have developed a workable plan, but the no-one’s-in-chargeness problem of “polycentric governance” (eek! jargon! read Ostrom! take my class!) means one step remains. From my conversation with Ian:

The biggest pitfall, the biggest danger is that the people who are working at the basin scale, the people who are in this network of people working together across state boundaries, understand that we have to take less water from the system. They have to go home and sell that to a political environment that’s really locally focused. There’s this political pushback back home, and all these deals ultimately have to be approved back home.

We’re in the pushback phase. As we enter a new water year – most water accounting systems begin Oct. 1 – there’s a hurdle there in front of you, people, now’s the time you’re supposed to jump.

“It’s not all that high,” Fleck said with his characteristic naive yet generous optimism. “You can do it.”

i would love to be a fly on the wall for

all of these and also to know for each system

what the actual “breaking” number is for each

aka at what point of flow for each system does

it break if it goes below that amount?

that’s the limit.

for people it is clear, we need so much water per

day to drink, go below that amount for a while and

we die.