Mancos Valley irrigation

CORTEZ, CO – The Spring Creek Extension Ditch Company got the OK this week from Colorado’s Southwest Basin Roundtable for a $29,000 grant to replace a 75-year-old siphon on the Spring Creek Ditch, where it crosses the Pine Valley Canal.

The ditch company has been delivering water to farmers southeast of Durango since 1901. There are currently 64 shareholders using its water, irrigating 5,435 acres. The siphon is at risk of failure, and the ditch company’s managers were asking the Roundtable for money to fund a share of the cost of replacement with a new pipe. The Roundtable, created to provide local input to and control over a portion of the state’s water spending, said yes. The ditch users themselves are covering part of the cost, and they’re asking the Colorado Water Conservation Board for the rest.

Upper Colorado River Basin agriculture, Montezuma County, Colorado

This is bottom up water management, governance at the retail level, and it says a lot about how the Colorado River Basin’s large scale issues cascade down to the local level – or perhaps how actions at the local level accumulate and filter up to the basin scale.

I was at the meeting for bigger picture stuff – a progress report on a study of Upper Basin risk as Lake Powell drops (I am working on this project with folks from the Colorado River District and Basin Roundtables from around the state). After our item, I stuck around to listen to the rest of the agenda, as one does. We New Mexicans are endlessly fascinated by the water management ways of our neighbors to the north. What is this wizardry you call “Roundtables” and “priority enforcement”?

In the Lower Colorado River Basin, where I’ve spent most of my time over the last few years working on a book, water management is a fundamentally distributive task. Water is released from Lake Mead in bulk and then distributed outward at a relatively small number of diversion points, tightly measured and well understood. You have a relatively small number of big water districts, allowing a relatively centralized decision structure. That doesn’t mean it’s easy, but at least the places where action is needed are relatively few.

The Upper Basin is completely different. Water starts in snowpack, trickling down a zillion creeks, gathering in streams and rivers with scads of much smaller diversions grabbing shares of water as it heads down toward the Green and the Colorado and the San Juan, the major tributary rivers that join to form what in the Upper Basin they call collectively the “Big River”. It is a fundamentally decentralized system.

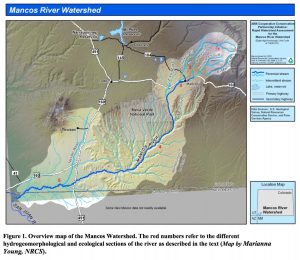

Mancos River watershed

Consider the Mancos River watershed, the next watershed to the east of Cortez. Lissa and I wandered its back roads today looking at farms (as one does) – five acres here, ten acres there, much of it hay and pasture. It’s lovely, green in July, the transitional geography between the Rockies and the deserts of the Colorado Plateau. If you’ve ever been to Mesa Verde, Mancos is the river valley that marks the eastern and southern edge of the park. In the 1990s (the most recent data I could easily find, an assessment done by Peter Stacey of the University of New Mexico), about 12,000 acres were being irrigated with water from some 46 separate diversions in the Mancos watershed, between its headwaters in the La Plata Mountains (a southern bit of the Rockies) and its junction with the San Juan just across the border in New Mexico. That’s 46 diversions in a tiny watershed, and pretty much every tributary in the Upper Colorado River Basin starts out this way – lots of diversion points each taking a relatively small share of the river. Compare that with Imperial County in California, where more than 450,000 acres are being irrigated with three diversions (maybe four if you count the two that serve Bard?).

As we enter into a basin wide discussion about the need to take less water from the Colorado River system – because there is less water in it than we planned for those many years ago – the nature of the conversation is very different if you have a relatively few large diversion points, or a staggering number of small ones.