When we talk about water scarcity in the western United States, it’s usually a conversation couched in acre feet of water and groundwater regulation and the Lake Mead bathtub ring and gallons per capita per day. But a dive into the data as I was cleaning up one of the chapters in my book-to-be reminded me that any conversation about water scarcity needs to start with whether we’ve got plumbing at all.

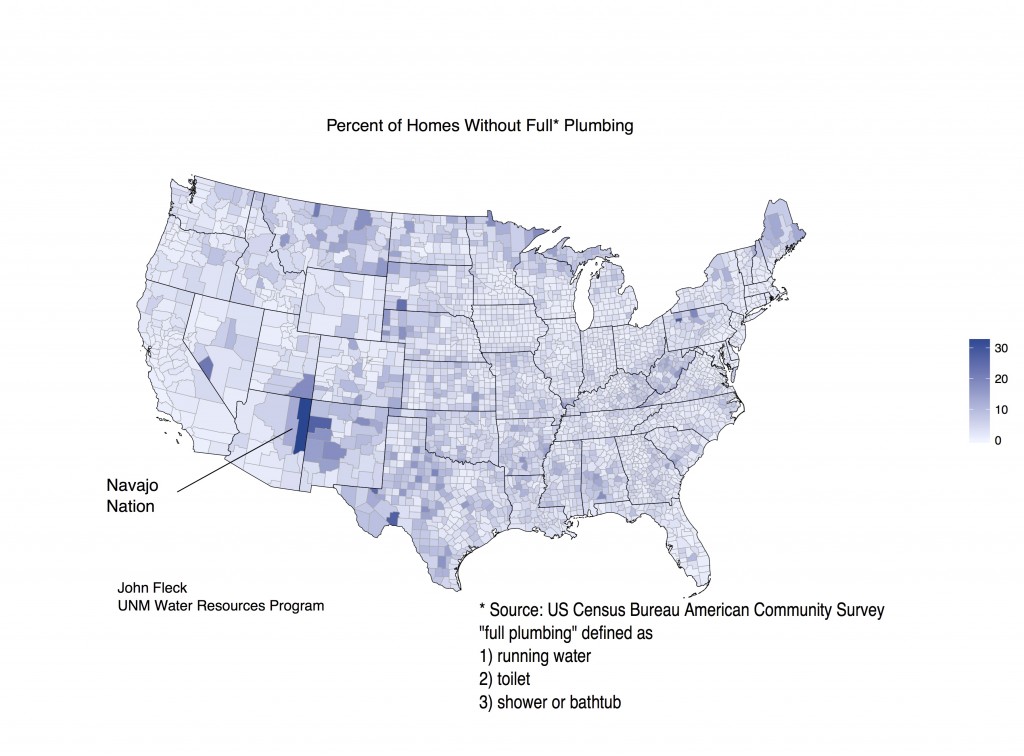

I’d been writing about water in Native American communities in the Colorado River Basin, and looking at Census Bureau data tables on who does and does not have indoor plumbing. But it didn’t really pop out until I plotted it up in a map:

Apache County in Arizona and McKinley County in New Mexico are, by far, the most water-scarce communities (by this measure) among populous areas in the Lower 48 states. This is the heart of the Navajo Nation, a native community that has struggled for years to win rights to the water implied by the promise of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1908 Winters decision. One in three homes in Apache County, nearly 11,000 of them, don’t have the full suite of toilet, hot and cold running water, and a shower or bathtub. Another 7,000 homes in McKinley County (27 percent) are lacking. I’ve written about this before, in stories about efforts to leverage the right to water under the U.S. legal system to an opportunity to actually bring plumbing to these distressed communities:

The public health implications for the communities that lack running water are enormous, Robertson pointed out. A 2007 federal study, noting that a wide variety of diseases are common without access to clean water, put the health care savings of the Navajo Gallup Water Supply Project at $435 million over 20 years. “There is a clear connection between sanitation facilities (water and sewerage) and Indian health,” the study concluded.

Some caveats about the data: I’ve left Alaska off (most of the highest rates of homes without plumbing are rural Alaska counties, but I don’t know enough about rural Alaska and native issues there to sort them out). My cutoff for “most populous” is arbitrary, but McKinley and Apache counties have far more homes without plumbing than those Alaska counties, or anywhere else in the nation for that matter. Shannon County in South Dakota, the Oglala Lakota reservation, has a 24 percent lack-of-plumbing rate. The county on the Texas-New Mexico border that looks dark on the map is Loving County. Almost no one lives there. Terrell County on the U.S.-Mexico border, west of Big Bend, has a 27 percent lack-of-plumbing rate, but hardly anyone lives there either.

There are only a couple of counties in the eastern U.S., all in western Pennsylvania, that have low rates of indoor plumbing, especially Forest and Potter counties. I think that’s Amish country?

There’s also a lengthy and fascinating discussion here about the methodological sensitivity involved when Census Bureau surveyors come calling to ask people about their plumbing: “Asking explicitly about flush toilets has resulted in negative attention from the public.”

Other than in towns, which are far and few, and the occasional housing project, most homes are scattered widely about the landscape at far remove from their neighbors or any infrastructure, such as paved roads. I was reminded of this earlier this month as I traveled though NW New Mexico, SE Utah, and NW Arizona.

Getting water, and even electricity, to many of the homes in the Navajo Nation and surrounding areas would be extremely difficult (and costly), to say nothing of the required maintenance over the years. It is probably not practical in many cases. I have paid only peripheral attention to this issue, so am not that familiar with the subject.

Navajo Gallup Water Supply Project will not bring running water to homes, but is intended to bring a reliable water supply to Gallup, Window Rock, and those communities lucky enough to be along the pipeline alignment (mostly US-491). I don’t know if any similar project is planned for Arizona.

Bill –

You are correct that the low population density and rural nature of the Navajo Nation makes this a difficult problem, but in conjunction with the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority, the Navajo Gallup project actually has the potential, if built out, to serve a substantial proportion of the underwatered Navajo Nation population – see the map (pdf: http://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/navajo/nav-gallup/pdfs/ProjAlignment-map.pdf ). The pipelines (there are two major ones, one along 491 and the second the Cutter Lateral through the Huerfano-Lybrook stretch) reach the most populated but underserved areas on the Navajo Nation. NTUA and the Indian Health Service (which funds a lot of the “last mile” infrastructure”) have had little incentive to build out the end user distribution system in these areas because there was no water to put in it. This will change that.

In the Navajo Nation’s Winters settlement agreement, the nation essentially traded water (its potential claims were far larger) for the financial help from the federal government to build out this infrastructure.

John,

I’d call http://sacredpower.com/about/ Sacred Power in Albuquerque. They have some history in the area of interest and may provide some insights.

dg

Pingback: Water insecurity: think poverty, not climate - jfleck at inkstain