Tony Perry in the Los Angeles Times had a good story this weekend talking about the agreement between the Palo Verde Irrigation District and the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California to move ag water to city use in the cities’ time of need:

Next year the agreement between MWD and the Palo Verde Irrigation District will mean an additional 120,000 acre-feet of water for MWD to supply its customers in six counties — enough for 240,000 families. It may also allow MWD to leave water in Lake Mead, helping slow the lake’s decline.

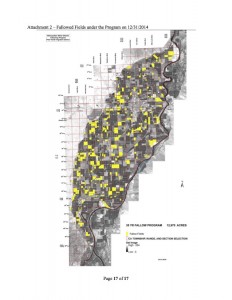

The city pays farmers for the right to fallow, guaranteeing steady cash flow, then more money in a year when the actually fallowing takes place, replacing lost farm income. The result is a patch of desert farm land that looks like this, to the left, where yellow parcels are fallowed land. You can see that it’s a checkerboard, with a lot of the land still in production.

I’ve been tempted to call this “sharing” of Colorado River water, but Brian Devine has pointed out the flaw in that language. This is a mutually beneficial business deal, not handing out cookies on the playground.

Palo Verde and Imperial: a comparison

Perry points in the piece to the contrast between Palo Verde and its neighbor to the south, the Imperial Irrigation District:

In the Imperial Valley, so-called fallowing agreements have caused political upheaval, recriminations and litigation. The federal government had to threaten to take the water without compensation to get the Imperial Irrigation District to agree in 2003 to sell water to San Diego.

But just to the north, in the smaller Palo Verde Valley, a 35-year agreement signed in 2005 with the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California has enjoyed public acceptance by farmers and local officials. More than 90% of landowners signed up for the voluntary program.

That’s right, but I’m not sure it matters. Despite the fussin’ and feudin’ in Imperial, the fact remains that we’re looking at more than 400,000 acre feet of conservation in Imperial this year through various means, including fallowing, a new (and very popular with the farmers, apparently) on-farm conservation program in which farmers get paid for conservation measures short of fallowing, system improvements like canal lining, and fallowing. A lot of that water is being sent on to metropolitan Southern California. Taken together, all of this ag conservation has become a critical piece of the adaptive capacity and resilience that Southern California is calling on to weather the current drought.