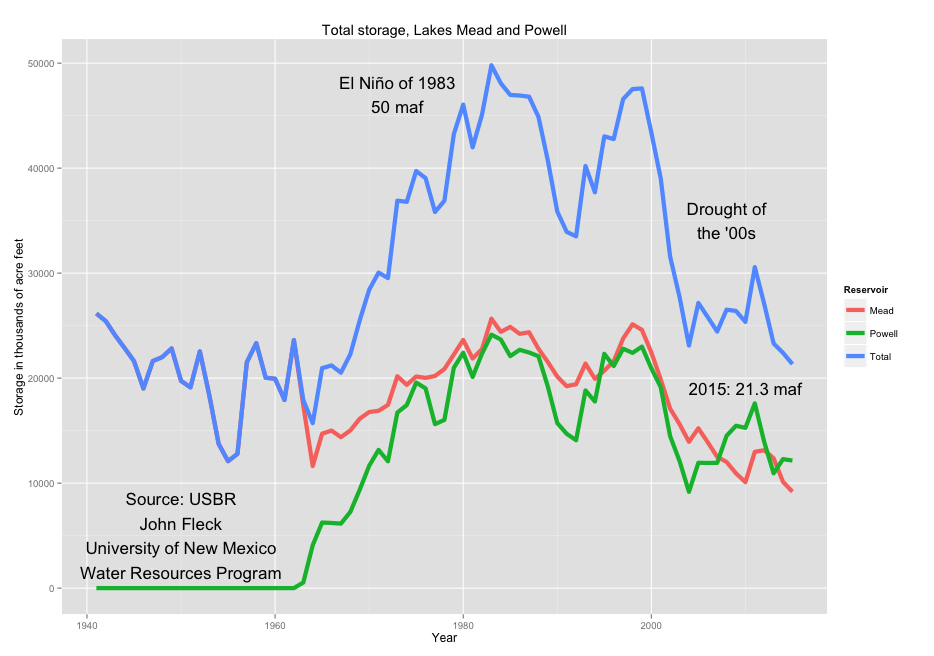

Updating my Colorado River reservoir storage spreadsheet today to make a graph for a friend was a pretty discouraging exercise. Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the system’s two massive reservoirs on which 9 states and a gazillion people and farm acres depend, are at their lowest combined level since 1967, when they were filling Powell for the first time:

I style myself as the optimist in the room. Staring dimly into the future, I think I can see what solutions to the West’s water problems might look like. My optimism comes from things like this, which appears on the agenda of tomorrow’s meeting of the Imperial Irrigation District board of directors. It’s an information item about an Arizona plan to conserve close to 100,000 acre feet of water this year, primarily by fallowing agricultural land in central Arizona:

This is water that will sit in Lake Mead, unused. It’s the kind of step that encourages me, but the details of what’s needed to carry it out help explain why Lake Mead is dropping faster than my optimism can keep it propped up.

It’s encouraging because it shows flexibility in the water use system. To slow or stop Lake Mead’s fall, we need to use less water by doing things like this. Central Arizona’s got an agricultural buffer to work with, imported Colorado River water pumped uphill via the Central Arizona Project. This agreement calls on some of that buffer.

But the friction here is discouraging. This is not as simple as just saving water. Dustin Garrick’s fascinating new book, Water Allocation in Rivers Under Pressure, goes a long way toward articulating what I’ve only been seeing dimly as I watch this process. Garrick’s work takes a deep look at the “transaction costs” of moving water around and, more importantly, in making the institutional changes (the changes in governance structures and rules) needed to change the way we move water around. (The “Coase” of the headline is economist Ronald Coase, whose work on transaction costs is incredibly important here if you wanna go full wonk on this stuff.) One of the key takeaways from Garrick’s book is that it’s not enough to point to how the rules are all messed up and Lake Mead is dropping as a result. We’ve got to really understand why the rules are hard to change. Those are transaction costs.

We’ve got a mechanism here that’s relatively straightforward on the water conservation side – fallow land in Arizona, leave water in Lake Mead. But the bureaucratic side is a nightmare of transaction costs. Load up the full document linked above and scroll down, and you’ll see that in order for Arizona to get credit for this arrangement under the Colorado River’s formal water accounting system, the agreement needs 16 signatures.

Sixteen signatures is a lot of transaction costs.

Nicely presented.

Not sure it’s covered in the book and is germaine to the subject you discuss regarding conservation efforts is that any water saved and stored is subject to storage and transport losses. Warmer temperatures, lower reservoir elevations, etc. add up. Evaporation from Lake Mead, how much will that dip in to AZ’s conservation of 100KAF? What would John Wesley Powell say now?

yes, Jim, i agree. much of what is conserved and stored above ground is subject to evaporative losses. then again, if the alternative is to use it to recharge aquifers i sure hope it would go to aquifers that are not already polluted.

more than anything i wish some percentage would be going towards wetlands and the Colorado River Delta restoragion efforts. at least you know those have benefits to wildlife and to recharging depleted aquifers….

When the rhetorical dust clears and the ink dries from all the explanations… we are still left with 1. Dwindling water 2. Increasing demand. It’s time to mandate strict safeguards now in the 7 states affected—before the inevitable happens: No pool permits….no housing starts….mandatory watersaving appliances & fixtures…..rationing to households. All this should have been done 40-50 years ago. And even with everything we do…there’s still too many people (and more on the way) living in all these service areas of the Colorado Rv. Unfortunately nobody listened to Charles Bowdens’ wakeup call in Killing the Hidden Waters.