Yuma is the last thing the Colorado River sees as it leaves the United States and disappears into the agricultural diversion canals of the Mexicali Valley, there to grow cotton, alfalfa and wheat. I’m headed there to see some environmental work being done on the lower river on the U.S. side of the border, but mainly to learn more about how Yuma County farmers use Colorado River water to grow food.

In the story of the Colorado River, Yuma is often overshadowed by its more muscular neighbor to the west, California’s Imperial Valley. But I have a personal fondness for Yuma, maybe because it actually puts its feet in the river (see picture above from when I was there last year). There’s a lovely city park on the river beneath the old bridges, a very well used park. To the east, upstream from where the photo was taken, the community has built a wetland project that’s great for birding. I’m taking binoculars!

With good soil, abundant sunshine and a reliable source of Colorado River water, the Yuma area farmers are sitting on what seems to be, per acre, the most valuable farmland in the Colorado River Basin. By county, it’s the second largest lettuce producer in the country, behind the Salinas Valley of California (Monterey County). But because Yuma farmers can grow during winter months when Salinas farmers can’t, Yuma dominates the U.S. domestic winter lettuce market.

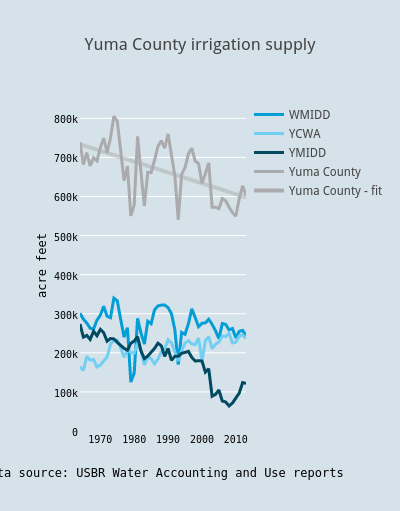

One of the most interesting features of farming in Yuma County (and this also applies to the other regions irrigated with water from the Lower Colorado River) is the relative reliability of supply. Sara Gerlitz and Chris Babis, in the University of New Mexico’s Water Resources program, are helping me look at water data over the last half century on that part of the river to try to better understand how the system can be brought into balance, and the graphs for Yuma County tell an interesting story (these are the area’s three large ag districts, so this doesn’t capture everything, but I think it’s getting the basic picture):

Two things have popped out of the data for me. One is the slow, long term decline. The second is the relative reliability of the supply over time.

One of the reasons I’m headed down is to meet with folks involved with the county’s big irrigation districts – Wellton-Mohawk (to the east of Yuma in the Gila River valley), Yuma Mesa (YMIDD in the graph) and the Yuma County Water Users Association. Each has a different geography and a unique story, but they share in common a reliability of supply that is unusual in arid climate surface water irrigation. Don’t get too caught up in the squiggles. A lot of arid climate farmers dependent on surface water would be seriously envious of squiggles that small.

As early users of Colorado River water, they have relatively senior water rights. With the multi-year storage behind Hoover Dam upstream, those senior rights mean that under the current water allocation rules, their supply remains reliable longer than a lot of other users in the basin who are more directly impacted by drought and climate change shortfalls. This is as close as you’ll get to a “drought proof” water supply in the arid southwest. Not surprisingly, people down there tend to look over their shoulders as a result, fearing that rich city folk will come after their water.

You also can see that, to the extent that the system is currently out of balance (hence the great emptying of Lake Mead), it’s not the fault of the Yuma County farmers. Their use is going down. (I think this is a land use shift story, primarily driven by YMIDD – that’s one of the things I’m hoping to better understand when I’m down there next week.)

The question of how Yuma got here is a fascinating one as we think about the future of water management in the Colorado River Basin. There’s a tendency to focus on the physical plumbing, which is pretty cool as water engineering goes – Laguna Dam, then Imperial, the amazing siphon under the river at Yuma, the saga of, and solutions to, Wellton-Mohawk’s groundwater pumping and salinity problems. But UC Santa Barbara anthropologist Casey Walsh argues that you can’t separate the physical from the institutional plumbing:

Water works possess the main characteristics of infrastructures: they are built into the landscape; they are shared by almost everyone; they serve both private and public ends, enabling the entire society to work more productively, ensuring better health, better standard of living, and so on. But this thumbnail definition allows us to think about social institutions and organizations as infrastructures as well. Social infrastructures of water include laws and the legal system, water user associations, and the bureaucracies and institutions of water management, whether private or public.

The need to understand this second piece, what Walsh calls “social infrastructures” and I’ve been calling “institutional plumbing” (I think I may like Walsh’s language better?) is what I love about Sauder’s book. It’s the story, told in careful detail, of the invention of a modern way of living in the desert – how settlers saw the land and the sun and the water and realized that if you could combine them, you’d have something. It describes how they elbowed aside native communities and then struggled to invent new ways of organizing themselves – private companies, public irrigation districts, U.S. federal government help. It is at times painful and at times comical – they had no idea how to build irrigation systems in a desert on the banks of a flooding river. The story of the Colorado River is often told in sweeping, basin-wide narratives (of either heroic irrigation pioneers or scoundrels fleecing the taxpayers). But it is in that process of organization irrigation district by irrigation district, mostly by people with good intentions and imperfect knowledge, that the story lies. That’s what I love about Sauder’s book, because as you get down to a more intimate scale, the story of the development of the Colorado River becomes more comprehensible.

While you’re down there John, take a side tour up to the North Gila Valley to view the Cesar Chavez childhood residence. http://reuther.wayne.edu/node/168

dg

DG – Any more details on where exactly this is? I’d love to go see it, my googling has come up short.

I’d contact the Yuma Sun newspaper or chamber of commerce for the exact place. Someone did a story a few years back on it for the Sun. Can’t remember exactly when.

While up in the North Gila Valley (drive up on 7E) is another “off the beaten track” place. http://smoter.com/flooddam/swastika.htm

Yes, Yuma has it’s oddities.

dg

Contact me if you need any Yuma background info, photos, etc. Yuma Visitors Bureau, 928-376-0100.

Our Yuma farmers use their water extremely efficiently.

Ann

We have been working on reconnecting Yuma with its riverfront for the past 15 years; two large riverfront parks, nine miles of waterside trails, and 400 acres of wetlands restoration. We have also formed an innovative partnership with the ag community…adopting their mass planting techniques for planting native trees. We are also keenly interested in protecting their water rights, and want to form a unique partnership of farmers and moderate environmental forces.

If you want a briefing and tour, please let me know

Thanks for the pointer to _The Yuma Project_ by Sauder, i just finished reading it last night and have put in requests for his other book (_Lost Frontier_) and a few other mentions (_Cadillac Desert_ and _The Big Thirst_).

One thing that struck me early in the book was how simple things like soil surveys and common sense were ignored. In the end it was all another continuation of the exploitation, to remove native lands and to destroy native cultures.