It rained kind of a lot in the intermountain west this month, which raises a fascinating question about the tools we use for Colorado River management, and the tendency of water managers and management institutions to base significant actions on median flow forecasts rather than managing with a flexibility that considers the probabilistic nature of the information forecasters are giving us.

In August, the Bureau of Reclamation announced that, for the first time ever it would curtail releases from Lake Powell on the Colorado River, reducing flows downstream through the Grand Canyon to Lake Mead and thence to the fountains of Las Vegas and Phoenix and the alfalfa fields of the Imperial Valley. Now it’s rained a whole bunch, and Lake Powell has a lot more water in it than we expected – enough, under a more flexible policy, to erase the need for curtailment. But it appears there’s no going back. In water supply terms, the Upper Basin appears to be the winner in the execution of this forecast-policy-weather edge case.

In water volume, the difference between a full release and a curtailed release was marginal, but the symbolic and therefore political implications are huge.

The decision was based on a rigid, cookbook-like formula contained in the 2007 interim guidelines for operating Mead and Powell. Once a month, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation takes the information giving to the agency by NOAA’s Colorado Basin River Forecast Center and updates its “24-Month Study“, which is basically a bunch of tables estimating inflows and reservoir levels for 12 Colorado River Basin reservoirs. Four times a year, in addition to the 24-Month Study, Reclamation also produces two additional reports, parallel “what if” sets of tables showing what would happen under the “wet” and “dry” ends of the probabilistic forecast issued by the CBRFC. But it’s important to note that, for purposes of the legally mandated interim guidelines, those wet and dry scenarios are not incorporated into the decision-making. The decisions are, by law, made based on the median forecast, without any flexibility to respond to what the forecasters might say about wet and dry.

These guidelines set decisions related to interstate water allocation and reservoir operations to the median forecasted inflow volumes. Unfortunately this approach does not consider the range represented by the forecast distribution, which leads to large uncertainties when a forecast distribution straddles important threshold values.

That’s from “River Forecast Application for Water Management: Oil and Water?“, an interesting new paper by the CBRFC’s Kevin Werner and colleagues looking at how forecast information is used by the water management community.

The operating guidelines also lock in a decision in August, based on median forecasts of the system’s behavior at the end of December:

The August 24-Month Study projections of the January 1 system storage and reservoir water surface elevations, for the following Water Year, shall be used to determine the applicable operational tier for the coordinated operation of Lake Powell and Lake Mead as specified in the table below. (emphasis added)

This is one of those edge cases, ” “straddl(ing) important threshold values,” that Werner was talking about. In August, the median forecast’s projected level of Lake Powell was straddling the crucial elevation level of 3,575 feet come Jan. 1. If it’s above, that mark, the guidelines call for a full release from Powell in 2013-14. If it’s below, curtailment happens. The August 24-Month Study (pdf) found that, with a full release, Lake Powell would be 1′ 4″ below the crucial 3,575 foot elevation level. So curtailment it is.

As I read the Interim Guidelines (and please, Bureau people and others in the audience, correct me if I’m getting this wrong) the “shall” in the guidelines means that we’ve made our decision based on the August 24-Month Study, and there’s no going back now.

Even though, as a result of what one of my water management friends has dubbed “the September to Remember,” Lake Powell is now five feet higher than the median forecast on which the curtailment decision was based. That would seem to put us safely above 3,575, meaning a policy that didn’t lock us into a decision each August might mean a bigger release this year.

To be fair, even the forecast at the high end of the CBRFC’s probabilistic range (pdf) wouldn’t have put us above 3,575 come Jan. 1. This storm was an outlier. So maybe I’ve just wasted a lot of your time on an argument that’s too clever by half. But it’s an interesting exercise for looking at the gaps between forecast, weather and policy.

John – my two cents on the issue, for what it’s worth — Mead and Powell are such large reservoirs and therefore utilized to manage water in the basin over multi-year periods that to adjust that management strategy based on short-term “weather” trends rather than establishing a strategy that reflects longer-term “climate” trends and sticking with that strategy does not seem prudent for overall system management. I think the 2007 management guidelines reflect that and are a good strategy. Short-term management adjustments are probably more appropriate with smaller systems/reservoirs.

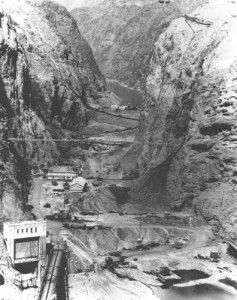

I like the new photo up top btw.

Pingback: Blog-ish round-up: Bloggers and others on the BDCP, the water bond, leveraging infrastructure investments, Lake Powell releases, Rim Fire, Cadiz, Morris Dam and more … ! » MAVEN'S NOTEBOOK | MAVEN'S NOTEBOOK