I first noticed it while I was out in the mountains of northern New Mexico back in the mid-1990s with Karl Karlstrom, a University of New Mexico geologist. I had tagged along on a summer field camp mapping exercise for a feature I was doing, and spent a good part of the day shadowing Karl and some of his students as they mapped a tangled section of old basement rock.

This will be familiar to earth scientists, but was a revelation to me – the way Karl with his little pouch of colored pencils sketched in the rock units as he walked. He was not simply recording data. The act of drawing was part of his construction of a mental model.

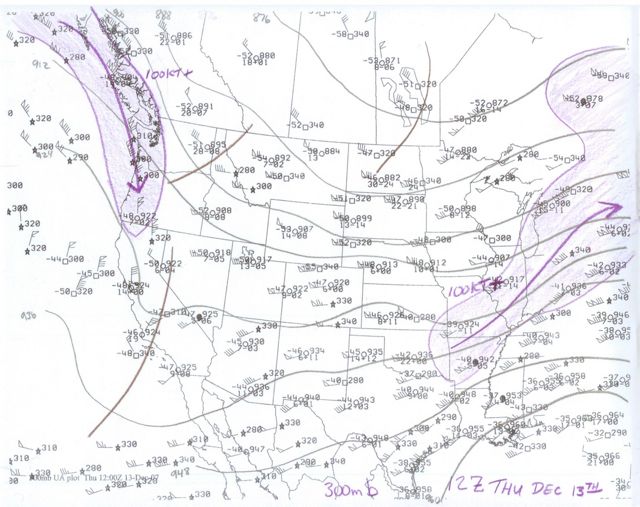

I’ve seen it again many times, most notably among meteorologists. In my book*, there’s a scene with forecaster Ken Drozd sketching out the movement of a storm across his daily weather map. Charlie Liles, the retired head of the Albuquerque Weather Service office, used to make these wonderful colored drought maps by hand.

Tom Pagano, the roving river forecaster, has a thoughtful explanation today on his blog about why it’s done this way:

Even though they have access to some of the largest supercomputers in the world, somewhere right now a meteorologist is sitting down with a set of colored pencils to hand-draw air pressure levels on a blank map. This is a generational thing, for sure, younger forecasters (myself included) often preferred to automate things and spend more time, for example, actually getting to eat lunch.

However, it is a meditation on the data. They spend time with their problem, giving it attention and thinking about its parts. As they draw, they consider each individual curve and line, while also subconsciously (or even consciously) marinating in the meaning of the broader pattern of the data. They are developing and exercising their intuition.

I’ve wondered too about whether it’s a generational thing. For the meteorologists, geologists and anyone else in the audience, do you sketch out your work by hand?

* Ideal for that bright youngster on your holiday shopping list!

Not only do I sketch out my field maps by hand, I force students to do so (especially in my sophomore field methods class). I want them to think about their observations while the rocks are in front of them – to think about what the hillside above them would look like from the air. Once they are comfortable thinking spatially (which is challenging to do), the process of making a map can reveal hypotheses that they might not be aware of, and can show them where to go to test their hypotheses. The map makes them think about how the types of data fit together, even in physically challenging conditions (heat, snow, mosquitoes).

Field-tough computers exist, and I need to learn how to use them. I can imagine a tablet or iPad that makes it possible to see the model emerge in the field, but I haven’t seen the perfect model yet. (I have also seen students record data electronically without making a paper map, and then not consider how the parts relate to one another, and miss opportunities to make observations when they’re outside on the rocks.)

There’s a structure/tectonics mailing list that has long, impassioned arguments about technology in the field, but they all seem to come down to the value of drawing a map by hand. And, yes, it’s the thinking in the field that’s important for a geologist.

(As an aside: I mostly use a chalkboard in class, rather than powerpoint, because I want the students to see how drawing is part of the way that I think.)

There are lots of automated methods for delineating watersheds, but I still prefer to do it on a topographic map with a pencil. Not only do I think it’s more accurate, but the end result is usually more aesthetically pleasing.

I’m not that old (36), and this is something I learned in school. I think it’s an essential skill for hydrologists and environmental engineers. However, I’ve noticed that younger colleagues don’t really know how to read topo maps.

I’ll agree with Kim. For my research I do less true mapping and more very high-resolution stratigraphic architecture (tracing and correlating every bed). Having students sit down and sketch the patterns they see on a nearby cliff-face outcrop forces them to really look at it. They might grumble and say ‘Well, I can take a high-res photograph and then analyze more efficiently’ … to which I respond, ‘We will ALSO do that, but it doesn’t REPLACE the act of observing-through-drawing while you’re here in front of it’.

So, for me, I’m open to new technology when it comes to documenting/capturing patterns but view it as supplemental not as a replacement. It seems too often the conversation naturally divides into an either/or dichotomy.

Brian – Excellent point about “not either/or”. The weather people I work with invariably use both. They have a lot of very sophisticated computer visualization tools, which they’re very good at using. When I was watching Ken do his forecast that day for my book, he spent most of his time on the computer, and the map-drawing was the final step, a sort of act of synthesis.

I’m in full agreement on the value of hand drawing. Like Matt, I’m not that old (45) and know of many hydrologists older than me who do all their head maps (water table elevation) using computer programs. I started my career working for an older geologist who considered computers to be nothing more than glorified typewriters and we used nothing but hand-drafted figures in our reports. To this day I’m automatically mistrustful of computer-generated contour maps. I think the intuition of the scientist is a critical part of the process of delineating something that is naturally part science, part conjecture. I also detest straight lines in something that represents a natural condition.

I think everyone has alluded to the idea that the two schools of thought here are largely dictated by generation/age. The newbies and younger generation such as myself are typically prone to lean on objective or computer-generated analyses (meteorological in my case), while the older generations generally prefer a subjective or “hand analysis”. There are always exceptions to this. A couple of our younger forecasters ritually perform mean sea level pressure analyses by hand every shift. For me, the benefits of an “aesthetically perfect” subjective analysis do not outweigh the cost (time). I usually only partake in subjective analysis in certain scenarios, such as when a fast-moving cold front is outrunning all computer model prognoses. This grants me more time to pour over diifferent model parameters, in hopes of completing a four dimensional conceptual image of what the atmosphere is doing. Although…errors in initial analyses are often the starting point for larger, amplified errors in computer model forecasts :-/

Traveling, and we had this very conversation this week. I used to draw my weather maps by hand back in the day before The Interwebs, and the old way was good at getting you to think about what was happening at the time.

Best,

D