When I was a young reporter covering Pasadena City Hall, I wrote a lot about the municipal budget, reasoning that budgets are where governments most explicitly establish and act on their priorities. But it was frustrating, because I just had one budget – no real points of comparison. So I set out one year to find comparable cities and compare – how much Pasadena spent per capita on cops, streets, etc., compared to other cities. This being pre-Internet, my little exercise involved picking out a handful of comparable cities around the LA area and driving to their city halls to sit down with their budget people and collect and compare the numbers.

What I found was head-smackingly obvious in retrospect. There was some fiddliness about how the governments allocated their money, and fiddliness with bonding, but basically cities that had greater revenue (mostly sales tax) spent more money. On cops. On streets. On whatever. The revenue stream presented a simple boundary condition.

I point to this analogy because available water can provide a simple boundary condition.

In a story last month, Matt Weiser of the Sacramento Bee introduced us to a farmer who behaved thus in the face of such a constraint:

Shawn Coburn, a farmer near Firebaugh, planted processing tomatoes this year on 500 acres that had been fallowed the last two years due to water shortages.

Pretty straightforward. Mr. Coburn didn’t have enough water in 2009 and 2010, so he didn’t plant those 500 acres.

Santa Fe, New Mexico, is another great example. The community faces real water supply constraints. It’s one of the only New Mexico cities that uses substantial supplies of surface water (from watersheds in the Sangre de Cristos), which are not super reliable. It has groundwater fields, but they’re not renewable, and the state’s regulatory structure places an additional constraint on them. It has a modest amount of imported Colorado River water, which it is using to the maximum extent it can. But it’s basically hit the limit.

As a result, a series of aggressive measures have pushed per capita water consumption down from 168 gallons per person per day in the mid 1990s to something around 100 gppd today. The details of how it did this are almost irrelevant. The key here is that, in the case of an imposed constraint, its residents reduced their water usage substantially. And it’s still a terrific little city. Cities do this sort of thing when they have to.

The fact is that we’re enormously profligate with water in the 21st-century United States, whether it’s irrigating marginal farmland or watering lush lawns and outdoor gardens and taking long showers. Faced with genuine constraints, we’ve shown, over and over, our ability to get by quite nicely using less water.

The real question is how we, as a society, go about imposing constraints and managing the transition.

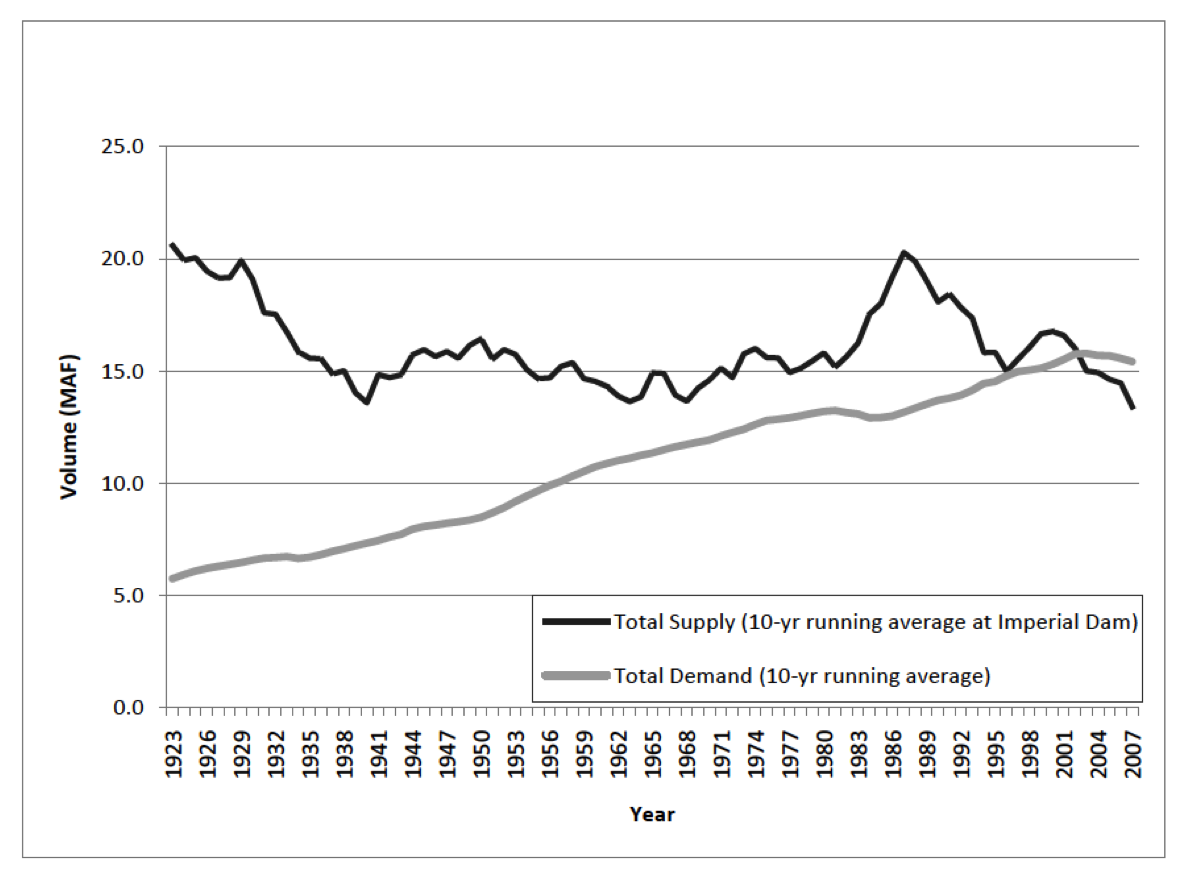

As regular readers may have noticed, I am much enamored with the Law of the River, the body of legal stuff that governs allocation of Colorado River water. As the graph shows, we have some real problems in the Colorado River Basin, with demand exceeding supply in the last decade. But we also have mechanisms for dealing with it in a relatively orderly fashion.

The Law of the River provides a framework for imposing constraints on each of the seven basin states and Mexico that will determine how much of the dwindling river each political subdivision gets. It is then left to those subdivisions to determine how to allocate the available water – or how to share the resulting shortages. So Santa Fe, for example, did not have an option of just going and grabbing more Colorado River water. The Law of the River, cascading down through state laws and regulations, imposed a constraint, and Santa Fe just figured out how to use less.

There are lots of other examples on the Colorado, including Southern California’s response to the Law of the River’s edict that it reduce its Colorado River use a decade ago. There is messiness within the states (witness Nevada’s struggle over whether Vegas can tap into rural groundwater to meet future needs). There is some real messiness with respect to groundwater mining. At the state and local community levels there will be winners and losers and some ugliness in the struggles to decide who fits in which category. I don’t mean to suggest this is an easy process. There’s a lot of heavy lifting to be done in communities across the West. But there’s a track record of responding to constraints successfully.

Ah, but the parts of California that don’t have a Law of the River to fall back on?

Yikes. Y’all don’t have your act together in terms of a framework for deciding where the limits are, for imposing constraints. One need look no further than Devin Nunes HR 1837 to see that California’s political system has not yet come to terms with the notion of constraints and the decisions that must follow.

Good luck, my Golden State friends.