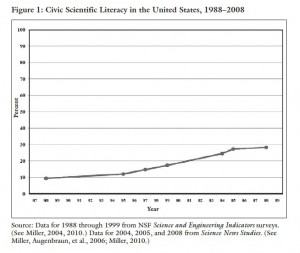

It’s hard to know whether this glass is half full or half empty:

It’s from “The Conceptualization and Measurement of Civic Scientific Literacy for the Twenty-First Century,” Jon Miller’s chapter in the new American Academy of Arts and Science report, “Science and the Educated American: A Core Component of Liberal Education.” (pdf here)

Miller has been trying to get empirical about the question of what Americans know and don’t know about science. As a science journalist trying to communicate with a broad lay audience, it is, for example, useful for me to remember that just 54 percent of Americans know that electrons are smaller than atoms. (Hey, that’s good news! It’s up from 46 percent a decade ago!) Having some feel for audience pre-knowledge is a critical piece of negotiating the space between science and the lay public, and between me and my audience.

The most recent data is important for a couple of reasons.

First, it suggests that the widespread belief that America is “dumbing down” is wrong. Miller’s repeat surveys, going back to the late 1980s in work done for the National Science Foundation, show a steady increase in public scientific literacy. But despite the steady improvement, most people just don’t know much about science.

It is common to hear the argument that, if only our educational system did a better job (or if only the media did a better job of teaching science), then outcomes of science-based political and public policy debates would improve. This data, which I’ve been using to help guide and inform my data since I discovered in the early 1990s, has always suggested to me that we’re never going to get far enough up that curve to make a big difference in those political and policy debates, and that we rather need processes that are robust to the reality that most folks just won’t ever know much science.

Eli thinks that the hardest part about writing science for papers is the lack of immediate feedback (e.g. the look on the audiences face) to judge if the level you are at is the right one. That and the diversity of the audience.

Pingback: Tweets that mention Scientific Literacy : jfleck at inkstain -- Topsy.com

What an interesting article. Thanks for pointing it out. Interesting to see the huge increase in understanding of DNA and it seems that something like the misunderstanding about genes in non-genetically modified tomatoes (49% think they don’t have genes) could be cured with a slight change in standard article intros.

By the way, that same report contains a chapter by Richard Muller with what seems to be an extract from his “Physics for Future Presidents” book. Don’t know if you’ve had a chance to read the full book yet, but I’ve enjoyed re-reading it a couple of times over the past years. He’s a good presenter.

The glass is half full.

Of groundwater tainted by big ag, but still.

Best,

D

John,

Thanks for bringing this up and referencing the report. Soon I will make time to read it.

I am a former university professor and am currently teaching a course on the intersection of modern genetic and biochemical breakthroughs with various ethical systems.

One thing that this course has reinforced is how quickly biochemistry and genetics is accumulating new knowledge. Many of my examples of how organisms work come from last week. The old examples come from 3 years ago. The really, really old examples come from a decade ago. When I taught a university graduate course in molecular biology, I had to change the course content by 50% a year in a vain attempt to keep up.

So, the base line of scientific knowledge that a literate person could know is increasing exponentially, at least in biology. If the measure of literacy is not increasing as quickly, it is not clear what the listed graph might mean.

An example, of which I have many, is that mice fetuses were injected with stem cells to fix a genetic anomaly. The stem cells were all killed in the fetus. Since the fetus does not have an immune system, it was unclear how the stem cells were killed. It turns out that the mothers immune cells flow through the fetus’s blood and kill invaders. Once the stem cells were matched to the mother (or surrogate mother!) the stem cells grew fine and were not killed. This research was published 3 weeks ago. Should a scientifically literate person keep up with such events?

John,

This is an important issue that American people should be trying to solve.

With increased access to information outlets such as the internet, usage in the US (77% of the population) as well as cable television in the last 10 years, many adults continue to be exposed to the basic concepts associated with various scientific fields. Perhaps, continued exposure to Science through these types of media, may help increase the percentage of adults with basic scientific knowledge. Furthermore, because of the amount of information that children and young adults are exposed to, the next generation should be more knowledgeable than older generations.

In general, Science is complicated and everyday something new is discovered. However, there is a basic knowledge that everyone should know. Example, DNA contains the genetic instructions, except for RNA viruses, needed to construct RNA molecules, proteins and other components of cells in living organisms. Moreover, this study recognized that some individuals finished their formal schooling 20 or 30 years ago, and we should not expect them to know a lot about stem cells, nanotechnology, etc.

Independent of the increase seen in the last 10 years, this is a problem because some of the reason that Miller pointed out. You may think that individuals representing a group or state in political debates over scientific issues such as the use of embryonic stem cells in biomedicine, novel energy sources and other issues have at least a basic scientific knowledge of these issues. Furthermore, of the groups, less than 28% of individuals that are represented may have sufficient understanding of the basic scientific issues discussed in these political agendas.

In the future, there will be a number of new scientific issues that will include not only biomedical issues but new high-tech equipment needed for the current military operations that will be part of the public policy agendas. U.S. investment in research and development enabled the U.S. to stay ahead of most of the countries in the world. However, because of the National Deficit those representing the American public will need to make tough decisions. How will the American public determine which research and development projects they should push for, if they do not even have the basic scientific knowledge that they should have? Better yet, how can we fix the problem of Science illiteracy in the United States?

Jose M. Pizarro