Investors need to take long term water supply risks into account as they think about municipal bonds, according to a new analysis by the environmental-investor group Ceres published this week:

The report shows that some of the nation’s largest public utilities may face moderate to severe water supply shortfalls in the coming years, yet these risks are not reflected in the pricing or disclosure of bonds that public utilities rely on to finance their infrastructure projects. There are about 50,000 public water utilities in this country serving an estimated 258 million Americans. The electric power sector is enormously water-intensive – it accounts for 41 percent of the nation’s freshwater withdrawals.

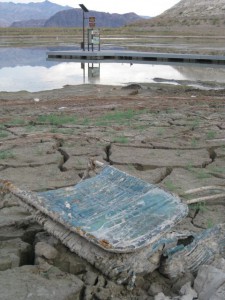

Lake Mead, October 2010

“Water scarcity is a growing risk to many public utilities across the country and investors owning utility bonds don’t even know it,” said Mindy Lubber, president of Ceres, which authored the report. “Utilities rely on water to repay their bond debts. If water supplies run short, utility revenues potentially fall, which means less money to pay off their bonds. Our report makes clear that this risk scenario is a distinct possibility for utilities in water-stressed regions and bond investors should be aware of it.”

The report comes as Lake Mead draws attention for dropping to historic low levels, and the first serious discussions are underway about a shortage declaration on the Colorado River. From the Ceres report, some examples of where the risk lies, including Los Angeles:

The Los Angeles Department of Water & Power’s water system bond received the highest risk score of all water utilities, based on tight restrictions on local water supplies due to environmental regulations and prolonged drought. The municipal system, the nation’s largest, is also highly reliant on vulnerable water imports, including the Colorado River. The utility’s water bond was rated “AA+” and “Aa2” by Fitch and Moody’s, respectively, earlier this year.

And the greater Phoenix area:

The Phoenix and Glendale, AZ utilities—systems with high reliance on increasingly expensive and potentially volatile out-of-state water imports from the Colorado River—also received high water risks scores.

The report also notes that the risk applies to the power sector, both because of dwindling hydro power from Hoover and other dams as water levels drop, and also because of the need for water to support new sources of power:

The Los Angeles electric power system‘s risks are driven in part by reductions in power generated at the Hoover Dam due to low water flows in the Colorado River Basin. The system may also see reduced power deliveries from one of its major coalfired power plants in Utah, due to heavy competition for dwindling cooling water flows.

(h/t Lisa Song)

I’m not sure Ceres is correct. Utilities rely on ratepayers to repay bonds, not what they deliver to ratepayers. If revenue streams have been designed correctly, a sharp reduction in consumption does not lead to a sharp reduction in the revenue stream allocated to pay bond debt. And if revenue streams haven’t been calculated correctly, the utility can change them.

At the end of the day, the utility really doesn’t want to go into default; ratepayers almost always end up paying more than they would have if they had adjusted revenue streams and/or renegotiated the debt.

(This is why consumption charges should only cover marginal costs plus conservation programs.)