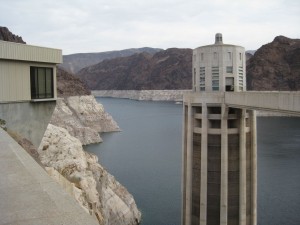

If you blow this picture up enough, you can probably see pixels of rock that have not been exposed since the 1930s. Or maybe not.

The surface elevation of Lake Mead hit 1083.18 feet above sea level today between 11 a.m. and noon Pacific time today, when this picture was taken. That is below the previous low – 1083.19 – on April 26, 1956. We can now unequivocally say that the drought of the ’00s and continued water consumption by downstream users has lowered the mighty reservoir to the lowest level it has seen since it was filled in the 1930s.

I tried this morning to explain to one of the tourists visiting Lake Mead the historic significance of the bathtub ring. He had jumped out of his car on an overlook on the Arizona side of Hoover Dam, and he was doing that thing where you hold your digital camera out at arms length to get yourself in the picture.

I told him it was a historic picture – that today Lake Mead had dropped to its lowest level since they built Hoover Dam in the 1930s. He looked puzzled.

Him: “Why’s it so low?”

Me: “Drought upstream. Water use downstream.”

Him: “It’ll fill up some day.”

And he jumped back in his car, headed for Vegas. This is how we do drought, American style.

I tried various explanations of what was going on this morning, from the quick to the complex, sort of testing my message as I wandered among the tourists visiting the dam, oblivious to the history I was trying to document.

It was hard to get across the drama. So far, the people suffering the most from Lake Mead’s decline seem to be the recreational boaters, who keep having to move their floating docks to chase the dropping water. I guess we can count that as a good thing. I mean, no one dies here in a drought, right?

We are sufficiently buffered by affluence that almost no one I talked to today had any inkling of what was going on. Just another tourist Sunday on Hoover Dam. The best I got was from one the folks in this picture, who were on a Sunday drive at one of the Lake Mead overlooks. One of them, a Las Vegas resident, knew the lake was way low, and said the solution was simple – somebody needs to have the political courage to make them release more water from Lake Powell, upstream.

I decided against explaining the Colorado River Compact, and the complex reservoir equalization rules in the 2007 shortage sharing agreement, that upper basin states are using less than their share of the river anyway, that Powell is low too, that it’s not that easy. But ultimately, I guess that’s what I have to figure out how to explain.

It’s OK, they’ll understand someday. 🙁

But see, John, you were trying to educate them with facts, IIRC the efficacy of which approach you seem to view differently when it comes to climate change. In this case we have a much more literal stock-and-flow problem, but why should people be more able to understand it?

An additional thought that just occurred to me (not novel, I’m sure, and Jared Diamond probably covered it) is that people really dislike considering the failure of large things that they’re involved in, to the point that they’ll stick with it even after the process of failure has become obvious. Just don’t look (or think about it) and it might fix itself, right? /rant

It’s really not all that hard. The political impetus for change will exist not when the CAP runs dry, not when the Colorado River Aqueduct is empty, not even when IID faces a 100+KAFY cutback. It will come when urban water agencies in LA and Phoenix tell their customers that all water is for basic consumption only and anyone caught irrigating their lawns will be fined.

By then, of course, we will be f*cked. I’m 47 now and childless. I don’t expect to live to see the American Southwest depopulate. But I expect my nieces will.

Most people ignore problems and are indifferent until the problem confronts them directly. The tourists you encountered were either there to see the new bridge or the dam.

Of the people you queried, the local guy stated, “Release more water from upstream.” Use political pressure.

The only thing he correctly touched on was the political end of things. Interesting thing, you can begin to get a feel for the political pressures by reading newspaper articles from different locations within the basin. What one reads in the Pueblo Chieftain will have a different slant as something that was reported in the Arizona Republic, the Review Journal, Salt Lake Tribune or LA Times. Politics plays a large role here.

Stakeholders are the other issue. As you have reported earlier, the stakeholders have worked collectively in trying to manage things through a series of agreements. Considering the situation, they have to.

The federal government is in the position of being the cop. Enforce the regulations or make any changes to the status quo and someone becomes unhappy with the results. Look at the situation in the Kalamath river several years ago. Water deliveries were cut, farmers were hurt financially. All that bad press and potential lawsuits.

Most people that have strong opinions on the subject tend to think that there is some mismanagement or complicity in the process. My own slant is that there are many dynamics in the equation. Like the water – most see things only on the surface. After closer attention you can see the details better.

There are times that I still feel like a tourist.

dg

“Release more water from Lake Powell.”

That’s a good one.

It may be impolitic for me to say so, but even though I live at the end of the pipeline in San Diego and we’re utterly dependent on the Colorado River, it still seems clear to me that California’s 4.4 MAF allocation is too much, having been based on a miscalculation of the river’s output. If we don’t reduce our take from the river, Lake Mead is likely to continue shrinking.

Pingback: Speaking of Water « Gambler's House

Most people don’t care because they don’t know. Unfortunately we’re rapdily becoming a nation of scientific illiterates and most people don’t care that they don’t know.

Things will change when we as a culture stop this “I’ve got mine” mentality and actually understand that all systems are connected and our actions have consequences. That may not happen in my lifetime.

Thats a weird picture. I had to look at the full-size to see it. Smaller, and the walkway to the tower blends into the rock wall in the background, and my eye couldn’t make sense of it.

I liked the stilling well, too.

William –

Looking at the picture, I totally see your point. This is why I am not a photographer.

Pingback: River Beat: The Investment Perspective : jfleck at inkstain

For the average Joe/Mary, drought will only matter when they turn on their bathroom faucet and no water comes out, or when the water bill quadruples (or increases ten fold). Everyone else who now “gets it” is a either a water manager, environmentally enlightened, or a climate wonk. That’s where we are and always will be.

Pingback: Who Needs to Understand Drought? : jfleck at inkstain

Pingback: Four Stone Hearth #104 « Sorting Out Science

Pingback: Four Stone Hearth #104

Pingback: The View of Mead From Upstream : jfleck at inkstain

Robin –

I would put your sentence the other way around. People don’t know because they don’t care. They might be disappointed that the lake is not as spectacular as it used to be, but as someone already said, watch them holler when they’re told they can’t saturate their lawns with potable water…

Pingback: It’s not as simple as just releasing more water from Lake Powell : jfleck at inkstain

Pingback: Four Stone Hearth #104 | Sorting out Science