It's a little emotional scar, of self-doubt. When I was a teenager at summer scout camp in the Sierra Nevada, I failed at the Mile Swim. They had a swimming area at the lake, and you could get your Mile Swim badge by swimming laps back and forth. I couldn't do it. I got too tired.

I've been depressed about my knee, not really able to do much on the bike that is physically challenging, so I decided I would swim a mile this weekend. For a real swimmer, it's really not that far, but I'd never done it before, and a thing I've never done before was the sort of challenge I needed. The Y pool was closed today, but I Googled and found a city pool that has lap swimming and did it. It only took about 45 minutes, and I kept going until they pulled up the lane markers and the kids started jumping in for free swim. In fact, I kept going through the free swimming kids, so I could get in an hour, which seems the minimum these days for my body to feel like it's right.

2200 meters by the time I was done. Not fast. I'm a pretty pathetic swimmer. But by my tally (the exercise numbers junkie has a log of these things), it's the fastest and longest swim I've ever done. Enough to banish the demons for a day.

Patrick Michaels has outdone himself.

In a Tech Central Station piece earlier this week, he first completely misrepresents an AP story about a new piece of research into retreating glaciers on the Antarctic peninsula. Then, with the straw man in place, he cherry picks the science to knock it down.

(click through for more)

First, the straw man. Here's Michaels' explanation of the press coverage that so concerns him:

Last week on Earth Day, AP newswire led with a real scare story: "Study Shows Antarctic Glaciers Shrinking." In doing so, the press, yet again, predictably distorted a global warming story.By "Antarctica" they actually meant the Antarctic Peninsula, which comprises about 2% of the continent. It's warming there and has been for decades. But every scientist (or for that matter, everyone who has read Michael Crichton's "State of Fear") knows that the temperature averaged over the entire continent has been declining for decades.

So did the AP story, as Michaels implies, suggest that all of Antarctica was warming? Let's check the actual story, by Emma Ross of the AP:

The first comprehensive survey of glaciers on the Antarctic peninsula has shown that the rivers of ice are shrinking, mostly because of warming of the local climate (emphasis added)....The Antarctic peninsula is a small segment of the Antarctic continent, located at the South Pole, and the behavior of the ice on the peninsula is not necessarily a reflection of what's going on elsewhere in Antarctica, said another investigator, David Vaughan of the British Antarctic Survey.

Temperatures seem to be much warmer on the Antarctic peninsula than on the rest of the continent.

OK, so Michaels has clearly misrepresented the AP story. How's he do on the science? Let's reload the key quote: "But every scientist (or for that matter, everyone who has read Michael Crichton's 'State of Fear') knows that the temperature averaged over the entire continent has been declining for decades."

"Every scientist knows" sounds an awful lot like Michaels is trying to argue that there's a scientific consensus on the question of continental-scale Antarctic temperature trends. The literature suggests anything but.

Michaels' brief for the prosecution comes from Doran et al. in Nature in 2002, which reported "a net cooling on the Antarctic continent between 1966 and 2000." But in citing only Doran, Michaels is engaging in a classic cherry-pick.

In a new review of Antarctic temperature data published this year in the International Journal of Climatology as part of the Reference Antarctic Data for Environmental Research project, John Turner of the British Antarctic Survey and his colleagues note other studies that have found trends opposite those published by Doran (for example Jones and Reid).

The bottom line message from Turner's paper is that data is too sparse and uneven to get meaningful continental-scale trends. That would explain why some researchers see a warming trend in their data while others see the opposite.

Does this sound like "every scientist knows" that Antarctica is cooling?

For the story of the extraordinary discovery of the Ivory-billed woodpecker, I'll leave you in the capable hands of Carl Zimmer.

My bird is a little less rare but I hope none the less delightful in a modest sort of way:

(Image courtesy USGS)

That's the killdeer, which tends to show up about this time every year in the urban wetland created in a big bend of the concrete flood control channel near my house.

Via the Arms Control Wonk we learn that NASA has chartered a new Exploration Systems Advisory Committee whose members include "Jeff 'Skunk' Baxter, Missile Defense Analyst, Beverly Hills, Calif." As Jeffrey puts it:

Yes, that is "Skunk" Baxter of the Doobie Brothers. How the hell does a guy in a band called the Doobie Brothers keep a security clearance? .... Perhaps our missile defense policy makes more sense if you're high.

In addition to the Doobie Brothers, Baxter also did a stint with Steely Dan, where on Countdown to Ecstacy he "sheds his outer skin and stands revealed as a Wild Boy."

Lonnie swept the playroom, and he swallowed up all he found.

It was forty-eight hours 'til Lonnie came around.

I think there's little doubt that this is the only album I own by a bona fide Missile Defense Analyst.

It says something - I'm not sure what - that Thomas Friedman has a higher Google ranking than Kinky Friedman.

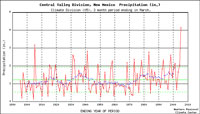

For my one reader who lives in the neighborhood, a weather update: 0.41 inches of rain overnight. That brings us to 1.63 inches for the month - the fourth straight month in which we've received more than double our normal rainfall here in Albuquerque.

That's precipitation for the first three months of the year for New Mexico's central valley climate division. You can see rather a spike for 2005. April will certainly push the spike up farther once that data is added in. (Data courtesy Western Regional Climate Center.)

As a regular visitor to a minor league baseball stadium, I have always been curious about the difference between those who will make the big leagues and those who will not. In rare cases it is obvious. I was in awe the day I say Pedro Martinez make his AAA debut in Albuquerque. I had never seen a change-up like that here. But usually, to my not-very-cultivated baseball eye, it is not at all obvious.

In today's New York Times magazine, Michael Lewis has a piece that wanders in quietly - almost like a baseball game, I suppose - through the question:

As Paul DePodesta, general manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers, puts it: ''A very small percentage of the players in the big leagues actually are much better than everyone else, and deserve to be paid the millions. A slightly larger percentage of players are actually worse than players who are stuck in the minors, but those guys usually aren't the ones getting the big money. It's the vast middle where the bulk of the inefficiency lies -- the player who is a 'known' player due to his major-league service time making millions of dollars who can be replaced at little to no cost in terms of production with a player making close to the league minimum.'' Just beneath a thin tier of truly great big-league ballplayers is a roiling inferno of essentially arbitrary promotions and demotions, in which the outcomes are determined by politics, fashion, misunderstanding and luck. Put another way: the market for most baseball players is hugely speculative, more like the market for, say, new Internet stocks than the market for stocks in companies with healthy earnings. The investors don't know how to value the assets.

Kids with the moral fire and mischief of youth. Nothin' like it.

The angel on the left is my daughter, Nora. The angel on the right is her friend Kelsey. The people behind them are - well, I'll let you judge for yourself. I think not angels.

The backstory dates to October 1998, when Matthew Shepard was beaten to death in Laramie, Wyoming. When Fred Phelps, the notoriously hateful homophobic preacher, brought his bile to Laramie to protest at Matthew's funeral, people were dumbfounded. When he returned to protest again at the trial of one of Matthew's assailants, Romaine Patterson was ready:

(click through for more)

I decided someone needed to stand toe to toe with this guy and show the differences. And I think that at times like this when the world is talking about hatred as much as it is right now, that someone really needs to show the difference. So our idea is to dress up as angels. And so we've designed an angel outfit. Our wings are huge. They're like big ass wings. And there's gonna be like ten to twenty of us that are angels. And because of our big ass wings we're gonna COM-PLETE-LY block him. So this big ass band of angels comes in. And we don't say a fucking word. We are a group of people bringing forth a message of peace and love and hope. And we're calling it Angel Action. Yeah, this twenty-one-year-old little lesbian's ready to walk the line with him.

When Fred Phelps' motley entourage came to Albuquerque, Nora and her friend made wings - big-ass wings.

The Phelpsites set up on one corner at the entrance to the University of New Mexico, and the counter-protesters set up on the other. And out of that crowd of counter-protesters emerged three angels, with these really big-ass wings.

They turned their back on the Phelpsies, and they raised their wings, and they just stood there.

After a few minutes, the cops, who were being pretty diligent about trying to keep the Phelpsoids and the counter-demonstrators apart, politely asked Angel Nora and her friends to take their big-ass wings back across the street. Which they did. They're good kids. They made their point.

Justin, who played Matthew Shepard when the kids did The Laramie Project last fall, held one pair of wings for a while.

I found the sight incredibly moving.

The Fred Phelps road show is coming to Albuquerque today. Daughter Nora and her friends are making angel wings.

Much duct tape and PVC pipe are involved. I am very proud.

Typical flow on the Rio Grande this time of year is about 1,000 cubic feet per second (cvs), but our gangbuster spring has the river flowing about five times average right now. That's nothing compared to a real river. The Mississippi River at Thebes, Illinois, is flowing at 247,000 cfs right now, and that's low for late April. But in the desert, we take what we can get, so Lissa and I went up to the Alameda river crossing at sunset this evening to take a look.

Thanks to Google Maps, that's the Alameda bridges across the Rio. The bottom one, the one that curves, is the new road bridge. They one above it in the picture is the old bridge, which they closed to cars but kept for walkers and bikers and such. It's the best spot to look at the river, because of the way it hovers over that island in the middle. Only this evening, it wasn't an island. It's mostly entirely under water, and the sand bar that you see in the top right of the picture is gone. It's lovely.

For folks in Albuquerque, a groovy new local metablog: Duke City Fix. As a bonus, the launch party yesterday gave me the opportunity to meet Jim "Black Helicopters" Scarantino.

Your Linguistic Profile: |

50% General American English |

20% Yankee |

15% Dixie |

5% Upper Midwestern |

0% Midwestern |

The thing is, I picked up "y'all" when I was in my 20s from a friend from Texas. It's just useful. The language needs a plural of "you." (From MJH.)

After ignoring pain in my right knee for a couple of weeks, I finally stayed off the bike this weekend. In the last two years, the only weekends I've gone without riding came when I was traveling and had no bike. Or when I was in bed with the flu.

This is not necessarily a bad thing. There are far fewer weeds in the garden, and a bunch of other necessary chores have been completed. And my knee feels a lot better. But I'm still jonesing for a ride. I'm going to the doctor tomorrow.

New Scientist has a story about some research by Vaseekaran Sivarajasingam at Cardiff University into violence on game days at the local pitch.

Sivarajasingam looked at emergency room admissions for assault from 1995 to 2002:

On non-match days, the number of assault victims averaged 21 per day, and on match days when Wales lost this rose to 25. But the situation was worse after a win, with 33 admissions per day on average.

Suggested avenues for further study: drunken revelry. From the paper: "Winning prompts celebration, a key component of which is alcohol consumption, and prompts the formation of crowds of intoxicated individuals, making interpersonal physical assertiveness more likely."

It's an old chestnut of those who would argue against relying on computer models to try to understand the trajectory of climate over the next century. " We can’t predict the weather a week in advance. How can we do it 100 years in advance?"

William Connolley has an excellent explanation of the way in which the argument glibly misunderstands the issue:

A better analogy is with throwing a (fair) die: you can't predict whether the next throw will be 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 or 6; yet you can be fairly sure that if you throw it 1000 times you'll get very bored. Sorry: If you throw it 1000 times, the average throw will be close to 3.5. And to pursue this a bit more, if you make the die a bit unfair (by, say, making the 6 twice as likely to come up) then you still can't predict what the next throw will be. But you can be sure that the long-term average will go up to... thinks... about 4 1/3.

But I wondered: is this just a straw man? Does anyone really make this argument? Not to worry. Tech Central Station (in the person of none other an eminence than James Glassman himself) comes through again:

We know how difficult it is to predict the weather for tomorrow; so, how are we going to predict the climate 100 years from now?

Thanks, Jim.

update: In rereading this, I realize another point that needs to be made. I'm not trying to use this as a defense of climate models. There are plenty of good reasons to think carefully about the use of climate models in formulating public policy. You've got to be careful in understanding both their strengths and limitations. This is merely meant to point out the vacuousness of one particular rhetorical trick used in an attempt to knock them down.

Let the record reflect the first Heineman-Fleck hummingbird sighting of the season: 10:43 a.m., April 16, 2005.

Lissa and I were sitting on the front porch snacking. The little guy zoomed up to the hummingbird feeder hanger. No feeder yet, but he was makin' the rounds. Think about it. This guy has been to Central America for the winter, all the way back, no Mapquest, no Google Maps, and a very small brain as well. But there he is.

Lissa immediately went in and filled the feeder, then began calling friends and family to report.

Patrick Michaels had a piece this week on Tech Central Station that made a good point about global warming and drought in western North America. His point is that we should be cautious in asserting a connection. But the math he uses to get there is, umm, unusual.

(climate wonks, click through for more)

The backstory: last fall, Ed Cook and his colleagues published a a paper in Science (paid sub. req. - more here) quantifying the extent of drought in Western North America over the last 1,200 years. The time of most widespread drought, they concluded, was "in AD 900 to 1300, an interval broadly consistent with the Medieval Warm Period."

If elevated aridity in the western United States is a natural response to climate warming, then any trend toward warmer temperatures in the future could lead to a serious long-term increase in aridity over western North America.

Michaels doesn't cite Cook et al., so maybe it's improper for me to infer that's who he's talking about when he refers to "some talking head (who) glibly associates western drought with global warming." But whether it's Cook and company he's referring to, he's clearly trying to knock the legs out from underneath the argument.

He does it by returning to a climate reconstruction published earlier this year in Nature by Moberg et al.. In his TCS piece, Michaels suggests that periods that in Moberg's data were "cool," such as the interval from 800 to 1000 AD, were also dry. He finds several centennial-scale periods when it was, by his definition, "cool" but also dry.

It's not clear how Michaels defines "cool" and "warm," but it seems to me a reasonable definition might involved temperatures higher and lower than the long-term mean. By that measure (Moberg's data is on line), the period from 800 to 1000 was about a tenth of a degree warmer than the mean of Moberg's data set. Similarly, 1200-1400, which Michaels calls "cool," was just a hair above average. In fact, if you look at the periods Michaels has chosen and actually calculate average temperature and area of drought (Cook's Drought Area Index data is also on the web) you'll find that in every case Michaels chose in his example, above average temperature coincides with above average drought, and below average temperature coincides with below average drought.

I don't know whether Michaels simply eyeballed Moberg's graph, or what. But the numbers don't support what he himself acknowledges are "rough comparisons."

I'm not saying this proves a global warming-drought link. Quite the contrary. I agree with Michaels' underlying point: caution is in order in drawing a connection between greenhouse warming and western drought. Drought is a complicated phenomenon. There is, however, some interesting evidence worth examining, including the Cook et al. paper and another recent effort by Mann, Cane, Zebiak and Clement that looks at an underlying mechanism that could explain a warm climate-western drought link.

Folks who live out west need to be paying attention to this. The variability of the drought cycle is going to be there, global warming link or not, and it deserves westerners' attention regardless. Population growth is likely to continue to be the dominant variable in the drought equation, swamping any trend toward increased drought that might come from global warming. In practical terms, after all, drought is best defined as happening at the intersection of two curves - water supply vs. demand. The demand side is exploding far faster than any supply side deviation that might be caused by global warming. And given our apparent commitment to global warming whatever we might do about greenhouse gas emissions now, we here in the west are sorta stuck with whatever might happen for the foreseeable future.

But folks shouldn't just accept Michaels' suggestion that this particular variable, marginal though it may be, can be safely ignored.

Cycling: Played hooky from work, allowing a leisurely ride in the bosque. My right knee's a bit tender, so "leisurely" was a must.

Baseball: There was a moment during the sixth inning this afternoon at the ballpark when Paul leaned over to ask if I'd ever seen a shutout here. I'm pretty sure the answer is no. The score at the time was Omaha 9, Albuquerque 0. Not to worry. It's AAA ball at 5,000 feet elevation. The pitching's, uh, uneven, and the ball flies outta there. Final: Omaha 10, Albuquerque 6.

Reading: I've been fascinated by the back-and-forth between Roger Pielke Jr. and the RealClimate guys over at Prometheus about the role the RealClimatists are playing. See especially this discussion. I've been thinking about what it might mean for my role as a journalist. More to come.

Garden: Weeds much the fewer out by the driveway.

Erik Stokstad has a story in Friday's Science (paid sub. req.) about a research team creating artificial droughts in the Amazon to try to understand the implications of climate change on the rain forest:

What's worrisome is that when drought lasts more than a year or two, the all-important canopy trees are decimated. Everyone knows that a lack of water eventually kills plants. But by pushing the tropical forest to its breaking point, researchers now have a better idea of exactly how much punishment these forests can withstand.These kinds of data will be indispensable for predicting how future droughts might change the ecological structure of the forest, the risk of fire, and how the forest functions as a carbon sink, experts say. Given that droughts in the Amazon are projected to increase in several climate models, the implications for these rich ecosystems is grim, says ecologist Deborah Clark of the University of Missouri, St. Louis, who works at La Selva Biological Station in Costa Rica. The forests are "headed in a terrible direction," she says. What's more, the picture includes a loss of carbon storage that might exacerbate global warming.

Charlie Liles, the head of the local National Weather Service Office, has done a good job of tracking freeze dates in and around Albuquerque. It's one of his most visible functions, keeping the gardeners informed.

His data pretty clearly tracks the trend: what the climate wonks call the "shrinking diurnal temperature range," which translates as "it doesn't get quite so cold at night any more," which is one of the hallmarks of greenhouse-driven climate change. Here in Albuquerque, the average last frost date over the long term is April 15, but for the 1991-2004 period it's April 1. A little bit of consistent change in the overnight temperatures can push those last freeze of spring and first freeze of fall dates around quite a bit.

I guess global warming's good for the garden.

This year we got down to 32 degrees April 10. My money's on that being our last freeze, and with the rainfall we've had this spring (more than four inches since Jan. 1, by far a record since 1890-something and more than three times average), the garden's all of a sudden busting out.

Lissa was exhausted this evening, but I pried her off of the couch for a quick wander through the garden to see what's growng. Out front, she spotted the lovely little iris you see above. It's at the front of our big iris bed, which is looking like it's about ready to pop, but not quite. So for now, it's the little early ones poking out here and there.

Out back, the apple trees are in blossom, and the wisteria is starting to leaf out. We've got this lovely miniature oak (we didn't mean it to be miniature, but one must adapt to one's garden ecosystem - it doesn't work the other way 'round) is covered with these cute little oakleaf clusters.

Our Harrison's rose (the yellow rose of Texas) has sent out runners, competing for space with the mums with which it shares a bed. My money's on the Harrison's, which has the advantage of being from hardy pioneer stock and being much preferred by the gardeners. (The ecosystem's not entirely on its own.)

Today's high was 76, and tomorrow's forecast to be much the same. I'm playing hooky from work, with a morning on the bike and tickets to an afternoon baseball game.

I love spring.

Ever since I met Michael Martin Nieto nearly a decade ago, I've been fascinated by his work on the Pioneer Anomaly. It's partly because the anomaly is so intriguing: the spacecraft, as they headed out of the solar system, behaved as though there's a little more gravity tugging on them than their ought to be. But part of the fascination is Nieto himself. He's a funny guy, who loves the mystery, and has a very careful attitude toward the whole thing. The hook here is that there are a couple of proposals for new space missions to test the thing. But that's just an excuse. I really just wanted to write about it again. From this morning's Journal:

When a scientist finds new data that conflicts with a well-established theory like Newton's or Einstein's, the first reaction is not likely to be to book tickets to Stockholm for their Nobel Prize ceremony. The more plausible explanation is that they've missed something.So for the last decade, Nieto, Anderson and others have banged away at the data, trying to make the "Pioneer anomaly" go away.

A software error was one of the first things they tested. They analyzed the data using software developed by two completely different groups, and got the same answer.

With that ruled out, they figured the most likely explanation was what they call a "systematic error"— something about the spacecraft that they've missed, perhaps a gas leak that's sending it off course, or some sort of uneven heating of the craft, or something of that sort.

When people offer Nieto that explanation he's likely to agree. "I say, 'Hell, you're probably right, but I don't do faith-based science.' ''

In other words, it's not enough to say it's probably a systematic error. You have to find it. But try as they might, the Pioneer anomaly team has been unable to do so.

(Note to the Planet GNOME and climate wonk audience: this is local Albuquerque politics. You can skip it. I have a fragmented audience problem. Whatever. It's my blog.)

There's so many intentional misstatements of fact in Pinhead Pika Brittlebrush's commentary on Quirky Burque, that (honest to God!) I really don't know where to begin. While I don't want to call fellow Albuquerque blogger Pika "Orange Helicopters" Brittlebrush a fool, she clearly doesn't have our best interests at heart.

Before addressing Brittlebrush's bizarre assertion that the cat fight should stop and be replaced by a more civilized discourse, I'll offer a disclosure Pika "Yellow Minibikes" Brittlebrush won't: she once had lunch with Greg Payne's gardener's second cousin, who also once had coffee with the guy who does James Scarantino's taxes.

Next thing you know, Scarantino and Payne are at each others' throats with a series of retaliatory smear jobs, and now Pika "Red Hovercrafts" Brittlebrush is trying to shut things down. Coincidence? Folks, c'mon... not in this business!

From today's Albuquerque Journal:

Tired of nuclear weapons that behave like finicky Ferraris, a small group of nuclear weapons designers is beginning to think about an alternative. Think Volkswagen Bug— nothing flashy, just cheap and reliable.The program, created under prodding from Congress and the Pentagon, is modest in size, just small teams of designers at nuclear weapons labs in New Mexico and California. But if it succeeds, it could lead to a new generation of nuclear weapons fundamentally different from the finely tuned, lightweight killers designed for the Cold War.

Pika's Duke City Doorways is up, including a door and a gate by my talented wife.

Thanks to all who responded to my plea for help making my way through the Jackie Chan oeuvre.

Dave makes a good point: "I think you have stumbled on to one of those questions that Buddhists use to clear the mind of thought for meditation. How can you judge whether a Jackie Chan movie is bad?"

Chan's made 90 films. Therefore the fact that four of the six people who emailed me with their favorites mentioned Drunken Master and Police Story suggests we've moved beyond statistical fluke into the realm of consensus. They're going into the Netflix queue.

Amazon-style, we also got a note suggesteing Buster Keaton. Good call, DW.

We signed up for Netflix, and I'm now confronted with a dilemma: How do I tell which Jackie Chan movies suck?

I got hooked almost 10 years ago when my sister dragged me to see Rumble in the Bronx, which was hilarious. After that, we'd see each new one together. I've taken no great joy in his crossover into American cinema, but I loved the old Buster Keaton kung fu master stuff.

My first Netflix pick was Project A, which left something to be desired. I mean, the kung fu bicycle scene was genius, but the rest of the film rather flagged. And his body of work is so, um, voluminous. I must find a filter.

Clearly, the bicycle shed needs to go over by the building, in the shade of that big elm tree.

I've always thought that good art eventually will stand on its own, but that one of the important roles of the First Amendment is to protect bad art.

Food/family: Nora, for her birthday dinner, chose sushi. Excellent.

Reading: I'm still picking my way The Great Maya Droughts. It's an oddly structured tome, with the author spending a great deal of time laying down exceptionally thorough theoretical foundations, as if defending against imagined arguments against what he's trying to say. It seems odd to me that one would need to defend the assertion that climate influences the arc of human culture.

Free software: DV's burnout post troubled me. What little time I have to devote to free software work these days I've been spending on libxml. I've seen Daniel be extraordinarily responsive, over and over again, to users with well-articulated needs and - and this is critical - a willingness to listen to Daniel when he reframes the problem.

Climate: From the Journal of Climate comes a tidbit from Shaleen Jain and colleagues of some relevance, I think. Variability of flows in four major western North American rivers increased over the last half of the 20th century. That means wetter wet years and drier dry years. They draw a dotted line between the trend, warming sea surface temperatures and projected 21st-century warming. They draw a solid line between the trend and water supplies in the West.

A bunch of threads to connect here:

Thread one: My own bias - invasive species are bad. The woods along the Rio Grande, my beloved bosque, are rich with native cottonwoods, but the riches are being inexorably choked out by the non-native salt cedar (Tamarix ramossisima). I am reasonably certain this is bad.

Thread two: Rudy Carillo's battle with the London rocket (Sisymbrium irio), a Eurasian invader that is thriving on the back of our record-setting winter precipitation:

The plant is the winter home to a species of leafhopper that carries the dreaded curly top virus. When the weed dies out in mid-spring (it's a winter annual from northern Europe, as the common name implies) it's certain that those same insects will move on to a variety of garden favorites, including chile and tomato plants, transmitting the virus as they proceed. According to the big agricultural school down south, curly top virus is deadly to the state's chile production: the last infestation, in 2001, destroyed between 40-50% of the crop.

My across-the-street neighbor, not noted for tidy gardening, has a front yard thick with London rocket. A couple of weeks ago, he mowed them. They're already tall enough again for the neighborhood cats to hide in them. I am reasonably certain this is bad.

Thread three: The worldchanging Jennifer Forman Orth, author of the Invasive Species Weblog. ISW is one of those Internet treasures, the carefully assembled insights of a smart person with an odd but useful obsession. I am reasonably certain that Orth's ISW motto - "It's Time to Wipe Out Invasive Plants" - is good.

Thread four: The cover story in the May 2005 Discover Magazine, in which Alan Burdick argues that my conventional wisdom, that invasive species are bad, may be simply wrong. While there are individual cases in which invasive species have caused very specific kinds of damage, the case is not generalizable, Burdick argues. In many cases, he writes, what I would call "invasive species" are more like benign immigrants, sliding into an ecosystem while causing little displacement.

I'm not saying I'm convinced that Burdick is right, but it's always fun to have one's preconceptions well challenged. I eagerly await Orth's review of Burdick's observations.

"Sundays, holidays, vacation time, we must be ready every day, all the time to do the right thing if the atomic bomb explodes: duck and cover!"

(Thanks to the Arms Control Wonk.)

Hadess: If you've not seen the original Manchurian Candidate, you should track it down. It's a terrific film for a number of reasons, not the least of which is Frank Sinatra's performance. More than just Vegas' best lounge singer, for sure.

Down in Albuquerque's far south valley, there's a lovely shady spot along the bike trail with a pasture, home to a single horse. Frequently the horse can be found over along the trail, poking his head through the fence to watch the cyclists.

This morning, as I passed I saw a guy who had pulled his bike over and stopped. He was feeding the horse.

I rode on, and a few minutes later the guy caught up with me. I asked him what he fed the horse - imagining Power Bars or something.

"Horse cookies," he said. Turns out he has horses of his own, and has these little baked horse treats that they love. So whenever he's headed on a ride down by the pasture, he sticks a couple of horse cookies in his pocket. He whistles as he rides by, then makes a quick turn around and by the time he gets back, the horse is over by the fence waiting for his cookies.

Friday, my yellow LiveStrong band broke. I'd been wondering how much longer I should wear it, and I figured that was an out. Then last night at dinner, Lissa asked me if I wanted to wear hers. Jeez. The cancer survivor gives you her LiveStrong band. You pretty much have to wear that.

Oh, yeah, one more unusual search string: global shit. Go figure.

It was with some pride this morning that I realized my blog is one of the top 10 hits on Google for dork freezer. But I am restive. I will not be satisfied until I'm number one.

Some other amusing search strings to come across the transom recently:

- lost carolina nuclear weapon

- death in virginia in 2004

- john fleck bug fixing

- guarrera pizza syracuse

That last one is a particular gem, something it seems could only possibly come together with sufficient monkeys and time, which is in essence how it happened.

There's a new paper in Science today by Arcturo Schmitnick of the Innsbruck Institute for Advance Studies suggestiing global warming may have a larger effect than previously understood on the world's population of Gnomes. Schmitnick used a coupled GCM/Forest-Elf simulation to try to determine the geographical distribution of climate change patterns against what elfologists know about current Gnome populations:

In the simulations, a disruption of the Atlantic hypertroidal circulation leads to a collapse of the Northern European Gnome stocks to less than half of their initial biomass, owing to rapid loss of nutrient reservoirs. Globally integrated export production declines by more than 20 per cent owing to reduced upwelling of nutrient-rich deep water in northern lakes and embayments and gradual depletion of upper water nutrient concentrations. These model results are consistent with the available high-resolution palaeorecord, and suggest that global Gnome populations are sensitive to changes in the Atlantic hypertroidal circulation. Globally integrated Gnome production declines by more than 20 per cent owing to reduced upwelling of nutrient-rich deep water and gradual depletion of upper ocean nutrient concentrations. These model results are consistent with the available high-resolution palaeorecord, and suggest that global Gnome productivity is sensitive to changes in the Atlantic hypertroidal circulation.

This could be good news for KDE, at least with respect to the Gnomes who depend on fisheries for their liveliihood, though it's less clear what will happen in the continental interiors, where Gnome forest patch agriculture dominates.

This, on the other hand, I find hilarious:

As a correspondent said, "I think it is homage."

Via Schweeb (hat tip arslinux) comes an interesting discussion of the Celt and the Romans and climate change:

The extent and duration of the Pax Romana in Europe was greatly facilitated by climatic conditions that favored Roman - as opposed to Celtic - economic, social, and political organization. Not only were Roman patterns of settlement and land use in marked dstinction to those of Celtic polities, the were especially suited to the mediterraneanized cliamte of Europe.

I'll definitely have to look into this some more, though I"m not sure I understands the connection between Boston basketball and global warming. My primary concern right now, though, is that it's too cold to go for a bike ride. I fear global cooling and a coming ice age. But the Celtics will no doubt prosper, as they did in the Bill Russell era - guess there's always winners and losers.