The triathlon kids call it a "brick."

It's a workout that assembles the pieces of a race, to get your body used to the muscle shifts involved in the transition from one sport to the next. I'm training for a duathlon in four weeks (my first), so this weekend I did my first brick, a Saturday morning run-bike-run.

Thing is, I can bike like a madman - not fast enough to keep up with real bike racers (as I learned later in the weekend - see below), but plenty fast enough to hold my own. But my running in the last five years has been limited as I switched to the bike, so I've been trying to get my running legs back.

On a snowy, windy Saturday morning I went to the gym and fired up the treadmill. Two miles on the treadmill, an hour on the stationary bike, then another two miles on the treadmill. And here's what was weird about it - the running went great - solid and reasonably fast for a slow old guy. But the bike in the middle was hell. After 20 minutes of running, it took half an hour to get comfortable on the bike, like I felt like I had some power in my legs. As soon as I hopped off the bike and got on the treadmill again, my running was blazing.

That's the point of the workout, at least in part, I suppose - to get used to what it feels like to make the transitions.

This morning my legs felt like lead - like lead bricks, come to think of it. I'd planned a 3 or 4 hour ride, but I kept finding excuses not to get out. Finally hit the road after 10 a.m., with a blustery cold wind and little whisps of snow showers all 'round. On the way out the bike trail, I hooked up with a go-fast racer boy, who explained he was on his way out to a race. Another excuse! I could go watch other people ride their bikes, rather than riding myself! We looped around to the business park up near my office where they'd closed off the roads and a bunch of college racers were hammering a criterium.

This was not the most pleasant weather to be sitting still watching a bike race, but it was fun, so I hung around for an hour or so watching the collegiate division, then the first part of the juniors. Once it got so cold that I really needed to get moving again, turning around and heading straight home seemed like a real tempting option. But I had bumped into a couple of guys who had been, like me, just sorta in the neighborhood in the course of their Sunday ride. They wanted to head up Tramway hill, a modest local climb. And the thing was, the wind was right for a great tailwind up Tramway, which is a treat of sorts. So why not?

This is where I get to the part of the story where I humbly explain that I can't keep up with real bike racers. It was one of those rides were I sat on their back wheels as long as I could, until that point (I know it well, been there a bunch of times before) where I see my heart rate creeping inexorably up to the red line. I was pretty pleased that I was able to hang wth them two thirds of the way up the climb, but that's where it hits a steeper pitch. And that's where I got dropped, never to see the two of them again.

The wind was at the right angle so that from the top of the hill I had a tailwind for a good part of the ride home. Snow was spitting from a sky that was more cloud than not, and the wind was gusting to 30 mph (50 kph). I made good time, but it was one of those rides where by the end it was just about getting my ass home.

I've been eating ever since. And my legs still feel like lead bricks. Tomorrow I rest.

Ah, the joys of free and energetic speech.

I try to explain some of the technical issues and political dynamic surrounding a proposal to build a uranium enrichment plant in New Mexico.

Nora was returning this evening from a three-day trip with her theater group. She called from the bus about 6:30 p.m., saying they'd be arriving at her school in 15 minutes. I timed it, drove over, and arrived at the appointed time at a dark and empty campus. Within five minutes, at least ten other cars had pulled up, followed shortly by the bus.

Another example of how cell phones change everything.

I had never heard of Alisa McCance, and I'm sure that McCance and Widdowson's The Composition of Foods Sixth Summary Edition is an exceptionally fine compilation of whatever it is that it's a compilation of. But no one carries the McCance name like Shaun McCance.

Just doing what I can.

Harvard law professor Randall Kennedy a few years back offered an interesting history lesson, the story of the intriguing case of Loving v. Virginia. Richard Loving (great name, huh?) had married Mildred Jeter in the District of Columbia, but when they moved to Virginia, they were charged with a crime.

Why?

Richard was white. Mildred was black.

God, the judge lectured them, had most surely intended the races remain separate, as evidence by the fact that He had plopped them down to begin with on separate continents.

One is tempted to laugh at the judge. The sentiments he voiced, however, decisively shaped peoples lives and were by no means idiosyncratic. A Gallup Poll indicated in 1965 that 42 percent of Northern whites supported bans on inter-racial marriage, as did 72 percent of southern whites.

This happened in 1967. At the time, 16 states had laws prohibiting inter-racial marriage.

Picked up Spencer Weart's history of climate science at the library over the weekend. It's a fine read. Like a good and serious historian of science, he makes clear that there are no "aha" moments, just a lot of stumbling around, with progress only possible once the ground has been prepared.

The issue of Lisp is, I think, an empirical one.

Back when GNOME made the move away from Sawfish for Metacity, at about the same time Sun came aboard, one of the wingnuts on Slashdot made a pejorative comment about the Sun programmers, questioning their abilities if they couldn't handle the Lisp required to maintain Sawfish.

The thing is, most everyone learned Lisp in school, right? And pretty much no one uses it now, right? I was reminded of this by a comment today from Joel Spolsky:

I think that if you try to ignore the fact that millions of programmers around the world have learned lisp and don't prefer to use it, you're in the land of morbid cognitive dissonance. And this attitude that "lisp is only for leet programmers so it's good because only l33t programmers will work on our code so our code will be extra good" is just bullshit, I'm sorry. Plenty of brilliant programmers know lisp just fine and still choose other languages. Most of them, in fact.

I've always had a soft spot for Lisp since I wrote a piece years ago about Greg Chaitin, the mathematician. Or is he a computer scientist?

I was sort of star struck, and we had coffee at a place across the street from the university, and he tried to explain to me randomness and halting and incompletness. And he told me that there was nothing quite so elegant as a Lisp. In retrospect, trying to write about mathematics was a fool's errand, and I don't try it much any more. Words can never do justice to the scribbles Chaitin sketched out for me as he explained to me the incompleteness of the real numbers - proved it for me, right there on a coffee-stained table. (I still love that juxtaposition, the purity of the ideal of the incompleteness of the real numbers on a coffee-stained table. The place is a pawn shop now.)

I didn't really know anything about computer languages then, and I imagined a Lisp as a shining city on a hill, a place where the purity of the ideal was made tangible, incarnate in code. And I suppose that's still what Lisp is, but down here by the docks where the work gets done, people seem to have set aside the beauty of Lisp for what must apparently have been more practical concerns.

So the bike's sitting in the garage with a flat. The front yard's torn up from the plumber's backhoe. And Lissa's lying in the bedroom with a face full of stitches from dental surgery.

But the toilet now flushes, and I just heard Lissa in the kitchen, rooting around for something to eat. I just need to pick up some tubes and a new back tire and I'll be set. Mmmm. Kevlar.

So in honor of Luis' birthday, yesterday I closed a bug.

And we're not talking about something cheap and easy, like using the dupfinder to zap one away. No, this bug required me to actually apply a patch. (OK, it was a patch submitted by a user, but still....)

Happy birthday, Luis.

update 2/29: In which I update based on Malcolm's helpful proofreading

As pointed out elsewhere here in the comments, Mark Boslough written an excellent summary of RS 2477 on the Enter Stage Right web site. It explains how this antiquated federal law is being used by the off-road big-tire people to try to enforce their "right" to tear up other people's land:

Use of RS 2477 is not just a theoretical threat. My family found out first-hand that the threat is very real. Off-road organizations are actively promoting it as a means of creating recreation areas on private land.

In my other blog I linked yesterday to an account written by Nat Cobb of his cross country Tour of Hope adventure. I promised Dano I'd run down the story I wrote last fall about Nat. Here it is.

"This thing is freakin' sick!" Seems like there's only one way to stop that boy:

So the inevitable plumbing adventure we've dreaded is now under way here at Casa Heineman-Fleck. It started late last week, and finally came to a head Saturday. Water currently arrives fine, but is not really capable of leaving. This means trips to our neighbor Alison's, or to the YMCA for a shower, or to Mom and Dad's. For our plumber, Mike, this is fabulous - not so much because of the financial benefit, but because it means he gets to rent a backhoe.

I've been following lately my friend Mark Boslough's battles over RS 2477, an old federal law that is at the center of some pretty important land fights in the western United States.

In Mark's case, off-roaders with giant-tired four-wheel drive vehicles have claimed RS 2477 rights to drive their vehicles up a creek bed on a ranch Mark's family owns in the mountains of Colorado. They claim it's a road. Mark's got some great pictures of the RS 2477 "road" here.

How cool is that, when you've got a five-time Tour winner working for you as a domestique:

"I think Floyd is probably the leader for tomorrow because he's in much better condition for the climbs. I don't know the climb, but he's climbing much better than I am and I suspect we'll work for him."

It apparently worked as Floyd Landis won Algarve.

Kevin Drum pointed his browser yesterday evening at this article in the Observer and then helpfully shared the results with us:

Climate change over the next 20 years could result in a global catastrophe costing millions of lives in wars and natural disasters..

A secret report, suppressed by US defence chiefs and obtained by The Observer, warns that major European cities will be sunk beneath rising seas as Britain is plunged into a 'Siberian' climate by 2020. Nuclear conflict, mega-droughts, famine and widespread rioting will erupt across the world.

This is the same report that good a good ride last month from Fortune, sending out some ripples not so much because of the science - this abrupt climate change stuff is old news but the source. When the Pentagon notices global climate change....

A narcissus in the front garden:

Our first flower of spring.

The new head of the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation makes an increasingly familiar argument - that nuclear power is a viable option for generating energy in the face of greenhouse-induced climate change: "If one believes the European Union projections . . . nuclear power will come back as the world starts moving towards carbon taxes. In Europe the feeling against burning coal is pretty strong." You don't hear that much here in the U.S., but it obviously resonates in places where attitudes toward greenhouse stuff are more solidified.

DCM and I followed the same path from Aaron's blog to Malcolm Gladwell's January New Yorker piece on the safety of SUV's. I couldn't possibly afford the time commitment of a New Yorker subscription, but Gladwell is quite literally my favorite journalist writing today, so I've been feeling a llittle bit parched by his recent hiatus. But his take on SUV safety doesn't disappoint, a classic Gladwell disquisition that gets once again at the intersection between culture and psychology's quiet truths.

According to Bradsher, internal industry market research concluded that S.U.V.s tend to be bought by people who are insecure, vain, self-centered, and self-absorbed, who are frequently nervous about their marriages, and who lack confidence in their driving skills.

OK, that's easy, picking on poor SUV owners. But the real revelation is the safety data: SUV's are demonstrably more dangerous than smaller cars - certainly for other drivers, but also for the people riding in them. Yeah, they have all that metal to protect you when you get in an accident. But they are far worse at avoiding accidents.

And then (I hate to belabor a point. No, that's wrong, I think we must belabor this point.) there is this, from no less than Andrew Sullivan:

The pictures of all those regular and not-so-regular couples waiting patiently in line for hours and hours and even days to get a piece of paper which probably won't give them any rights at all - that's revolutionary in the public consciousness. Suddenly, it's not the gay pride parades and mardi gras festivals that illustrate gay lives. Suddenly, it's love and patience and kids and umbrellas and bouquets and tuxedoes and all the other bric-a-brac of living.

On my earlier squib pointing readers to the Albuquerque Journal's gay marriage poll, I drew several unexpected responses from readers who think same-sex unions are "abnormal". Josh Marshall last night published an amazingly touching letter from a reader about another time and place in our society in which the same argument was made:

I'm 62 years old and grew up in Missouri. When I married my first wife, who was Japanese American, we had to do so in another state. At that time it was against Missouri state law for interracial marriages to take place. Times change.40 years later the pain of that state-sanctioned inequality, which made some couples second-class citizens, still stirs an old, deep-felt resentment. While I'm not gay, I certainly have sympathy for the state-sanctioned unfairness that gay couples endure and believe that in another 40 years (probably much sooner) gay marriages will be a simple, accepted fact of life.

Just a note to point out that I prize thoughtfulness and civility in discourse, and I feel completely comfortable deleting that which is within my power to delete when it doesn't meet that test. For example:

It's sick, disgusting and immoral and all the liberal freaks around the FOSS community will scream, but it's true.

It had much worse than that to offer, but you get the idea.

I also delete all the human growth hormone comment spam.

Should two people of the same gender be allowed to marry in New Mexico?

(Update: I might not have made this clear. You're supposed to click on the link above and vote. Not that I mind having votes left in the comments, but that wasn't really the purpose.))

Talking to a friend earlier this week whose wife is a dancer. I was pointing out that I get a bit crazy if I don't exercise, and he said the same thing happens to her - that he has to make her get some exercise sometimes just so she's not unpleasant to be around.

It's common to hear that from people who exercise a lot. I know it from my own experience: if I go more than a couple of days without cranking up my heart rate, get kinda anxious and depressed, lacking mental focus, that sort of thing. I know enough about how science works not to trust anecdotes, but this is me, so I take it seriously.

Turns out, according too a piece this week in Velonews about exercise and depression, mine and my dancer friend's anecdotes are commonly reported, but apparently no one has ever studied the issue:

Many people describe feeling worse, cranky, irritable, and moody if they don't get their exercise - a phenomenon that, to the best of our knowledge, has not been formally examined.

There's good data suggesting a link between exercise and a reduction in stress, and between a reduction in stress and a reduction in depression - a place I'll gladly go. But, as scientists like to say, clearly more research is needed.

Those of you who depend on western snowpacks for skiing or, perhaps more iimportantly, drinking water, might be interested in Ruby Leung's new global climate models simulating snowpack in the western U.S. in a greenhouse climate. I write about this at ABQJournal.com.

I don't wanna belabor this Pantani thing, because there's something a little bit unseemly about a 45-year-old man even having sports heroes, let alone one as questionable as Pantani became. But back in 1998, when I was first learning seriously about cycling, it was Pantani I admired.

And in particular, it was this day, the 16th stage of the 1998 Tour, over the Col de la Madeleine.

This was before OLN, so I followed the day-to-day stuff with Steve Wood's daily dispatches for Velonews.

Jan Ullrich was the defending champion, and was riding well until the 15th stage, a mountain stage, when he cracked and Pantani put big time on him. Unwilling to cede anything to the Italian, Ullrich came out hard the next day, the 16th stage, attacking at the bottom of the day's final climb. It was futile but noble - there was no way Ullrich could make up the time he'd lost.

Pantani went with him, just marking his wheel. No one else could follow. And they rode together, old champion and new, banging away for nearly two hours, by themselves.

That fall, when I inherited my "new" bike, I had it painted celeste. And as soon as I could, I started riding it in the mountains.

Seth Nickell's point about the distinction between what people will do with a computer, versus what they could do is the perfect antidote to the endless "they crippled my window manager" arguments. The arguments seem to have lessened thanks to stern management of GNOME's goals, but Seth's thermostat example is a classic if needed for future use.

When I first came over to the GNOME world four years ago, one of the first bits of documentation I wrote was for the old desk-guide applet. I was fascinated by the fact that you could have a bunch of different desktops that you could click back and forth among, but the terminology and strange behaviors left me a bit confused. I ended up writing this:

NoteDifferent window managers use different jargon to describe virtual desktops and the subdivided workspaces within them. Enlightenment divides your working area into "desktops," and then subdivides those into "screens." Sawfish, formerly known as Sawmill divides your working area into "workspaces" and then subdivides those into columns and rows. Desk Guide applet calls the workspaces "desktops" and the areas within them "viewports". See your window manager's documentation for more informaton on setting up and managing your virtual workspaces.

Yikes! That's way worse than Seth's thermostat. And now I can't remember. Was it viewports the evil Havoc Pennington took away? Or was it workspaces?

We may be allies on some really big things, but the British government's top science advisor isn't so keen on U.S. policy with respect to climate change, accordng to the Independent:

Britain has attacked President George Bush's administration for failing to take action on global warming, as part of an intensifying drive to get the United States to treat the issue seriously.Professor Sir David King, Tony Blair's chief scientific adviser, took the opportunity of a speech on Friday at the American Association for the Advancement of Science to brand the President's position as indefensible.

Arriving straight from talks with senior officials in Washington, he pointedly reminded the US that it has signed up for the Kyoto protocol on combating global warming, which the President has been trying to kill.

And he added: "Climate change is real. Millions will increasingly be exposed to hunger, drought, flooding and debilitating diseases such as malaria. Inaction due to questions over the science is no longer defensible."

King, you may remember is the one who, in an article in Science last month, said climate change was more dangerous than terrorism.

Jaime and I went up a new road (new for me, anyway) yesterday, out into the piñon-juniper woodlands north of town.

If there is a quintessential landscape of my home, it is the PJ, vast low-slung forests sweeping north from where I live. The trees, gnarly and stunted, have no majesty whatsoever, but a sort of approachable modesty, hardscrabble survivors that I have always adored, since I remember camping among them at Navajo National Monument in northern Arizona as a kid.

Albuquerque, at around 5,000 feet, sits near the lower elevation margin of good PJ habitat. You can find piñon-juniper woodlands south of us, but not much. As the elevation drops from here, you get creosote bush deserts - beautiful in their own right, but not the classic high desert look that for me defines this landscape. But a drive north and west, into the higher country of the Colorado Plateau, gets you into PJ quick.

And, given the time, a bike will get you there too. We rode up the river, through the cottonwoods, then up onto the west mesa through the ugly suburban sprawl of Rio Rancho (trust me, not as scenic as the name might suggest).

The northern-most town of the Albuquerque metropolitan area is called Bernalillo, a little village straddling the Rio Grande that seems to make its living off of roadside fast food and gas, along with a wallboard plant and what I believe to be the region's largest Tuff Shed dealership. Beyond Bernalillo to the north is Santa Ana Pueblo. The Santa Anas, who have lived here since the 1500s, have most recently hitched their economic fortunes to a quirk of U.S. law that allows native tribes to establish casinos on their land. On the map at the link above, you can see the golf courses and hotels that have been built as part of the Santa Anas' gambling resort ambitions.

The happy side benefit, for us, is the nicely paved Tamaya Boulevard, which leads up through rolling hills of piñon and juniper. When you pass the turnoff to the Twin Warriors Golf Club, the road drops from expansive to two-lane and rough. It leads to Jemez Dam, and pretty much no one goes to Jemez Dam except the bike crazies, so we could just spill out into the roadway, taking as much space as we needed.

To those of you who don't ride, trust me - "rollers", as we call undulating terrain, are the best. You can bang on the uphills, catch your breath on the downhills, then bang up again.

Jaime and I took the rollers as far as our predetermined turnaround time would allow, then kept going a little farther to a spot with a view.

To the north, you could see the lip of the great volcanic mesas of the Jemez Caldera. To the south, from where we had come, our city was laid out along the Rio Grand Rift's gentle valley as far as we could see, flanked to the east by the Sandia's, still white on their north-facing slopes from last week's storm.

Around us, in the gullies where the sun wasn't quite hitting, we could see bits of snow still in the shade. I imagined the piñon were happy.

On my previous discussion of Google and first names, an anonymous commenter asks: "Guess who owns Miguel?"

From today's Journal:

The mystery is this: Somehow a little more than 200 million years ago, hundreds of dinosaurs— possibly thousands— died together, at one place, at one time.Entombed together in stone, they were left for Rinehart and his colleagues to dig up, to try to figure out what was responsible for this prehistoric slaughter.

The death of Marco Pantani is a sad day for my sport. Seeing his decline these last few years was sad. Knowing of his drug use was unfuriating.

Seeing him dance up mountains will always remain special.

I know I have defended the robotic missions to Mars against charges that they cost too much, but Robert B. Gagosian, in today's Washington Post, gives voice to an alternative perspective based on questions about parts of the Earth that we have not yet studied well.

Gagosian, head of Woods Hole, loves the Mars stuff, but offers a strong, apples-to-apples argument about the exploratory science that could be done here on Earth for a comparable cost:

Miniaturization of sensors and telemetry technology has created a new generation of ocean observatories that enable us to learn more at less cost. We needn't rely only on ships for exploration. Flotillas of battery- and solar-powered observatories, some as small as a soccer ball, can report back measurements 24 hours a day from anywhere on Earth, regardless of weather. Some are anchored in place or flow with ocean currents; some are autonomous robots that swim on a programmed path for months at a time; some are installed on the sea floor, some on the coast, some at the sea surface and some part way down in "mid water."We are in a new age of oceanography, one in which giving the ocean its own instrumentation has become an economic and technical possibility.

The cost of building a network of hundreds of sensors to wire the oceans: about $1 billion over 10 years, a little more than the cost of the two Mars rovers.

What's the payback?

The oceans affect climate and weather, and thus the human condition, around the world. Ocean observatories can reveal conditions that affect fisheries, shifts in weather and long-term climate change. They can illuminate the migratory patterns of marine mammals, the reasons for drought or floods, and the fate and long-term effects of pollutants. They can detect in real time tsunamis, undersea earthquakes, volcanoes and extreme weather at sea, improving prediction of their devastating effects at sea and ashore. Figures we have come up with show that better predictions of ocean conditions could produce $1 billion in annual savings from better mitigation or prevention of damages.

This is clearly not an either-or thing, but when we're talking about spending a billion dollars for this or that, it's a useful point of comparison.

I'm sure opposing counsel would be willing to stipulate that Don Knuth is cool, but for the record, I'd like to submit the following evidence: Don Knuth is the first result when you search for "Don" on Google.

I found that yesterday via a typo accident, which got me to Googlewandering looking to see who owns other first names.

- Bob Dylan owns "Bob", though "Bob The Builder", Bob Marley and the Church of the Subgenius score well.

- The British National AIDS Trust owns "Nat", though our Nat Friedman is now up to third, ahead of Nat Hentoff.

- If you're looking for "Fred", you'll have to fight your way past the Federal Reserve Economic Data web site.

- It's heartening to see that our most holy Mother of Jesus comes in ahead of cosmetics giant Mary Kay. Whatever one's religious beliefs, that's a sign of properly ordered priorities.

- My name seems to be owned by John Bartlett's Quotations: I have gathered a posie of other men's flowers, and nothing but the thread that binds them is mine own.

Driving home from work the other night on the freeway, I was passed by one of those fast red sports/muscle cars Detroit is making today - a Dodge Viper or some such.

Albuquerque's "rush hour" is not much to speak of, not really a traffic jam, just enough congestion to keep you from going any faster than anyone else, which is always a little bit slower than some people seem to want to go. Such was the case with Viper Man, as he changed back and forth from lane to lane, looking for an opening that would allow him to go slightly faster, saving no more than a second or two with each move.

He seemed so muscularly, testosteronely out of place, all dressed up in that silly red Viper, that he reminded me of Disco Stu, desperately making move after move and going nowhere.

That's one of the intriguing corollaries of a hypothesis being put forward by William Ruddiman, an emeritus climate researcher at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. Ruddiman argues that, through deforestation and rice farming, humans have been having a significant effect on greenhouse warming for as much as 8,000 years - not just that last century or so that is the more common view today.

Ruddiman lays out the thesis in a piece in the December Climatic Change, and there are good news stories about his thinking by Richard Kerr in the Jan. 16 Science and by Betsy Mason in yesterday's Nature. (I won't bother linking directly to the articles because of paid subscription juju - if you've got that, you'll know how to find 'em.) New Scientist also ran an article in December, when Ruddiman spoke about this at AGU.

The nut of Ruddiman's argument is that carbon dioxide and methane levels over the last 10,000 years, as seen in ice core records, do not correspond with trends one would expect based on natural solar-induced cycles. The anomalies, he argues, corrolate well with a number of basic innovations in human culture, including the spread of farming across Eurasia, and the rise of rice paddy agriculture.

The plague argument, which is really just a teaser for the much more complex story, goes like this: massive deforestation from the beginning of the age of farming 8,000 years ago across Eurasia is responsible for measured increases in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which lead to much more significant and early warming than is currently widely recognized. But plague, by killing a huge portion of the European population, changed that, as large swaths of farmland reverted to forest. Less greenhouse muck in the atmosphere means less warming, and presto! You've got a Little Ice Age.

Ruddiman also pegs another big carbon dioxide decrease to an issue that's much in debate in American archaeology. When Europeans brought their diseases to the Americas in the 1500s, they killed off a more-than-plague-like proportion of the continent's native population, causing a reforestation here that corresponds to a measurable decline in atmospheric carbon dioxide, Mason explains. This goes to the heart of the debate about how truly "wild" the American wilderness was when the first European explorers got here, and how large the native population might have been. One faction among the archaeologists studying this argues that the Native American population was enormous, living, farming, etc., essentially everywhere. It took Europeans several centuries to "explore" the continental interior, according to this argument, and by that time their diseases had preceded them, wiping out the native population. By this argument, places that seemed "wild" - forested, unpopulated by humans - when the Europeans got there had only recently become so, on account of because our diseases had only recently killed all the people who had lived there.

Having lived essentially my entire life in arid climes, there are some things I take for granted that perhaps I shouldn't, as Nat helpfully points out:

There are, apparently, some advantages. Like you can leave crackers out on the table and they don't get stale overnight. Wow.

Well, no, he didn't.

A web page devoted to famous quotes attributed to Twain that he didn't really say.

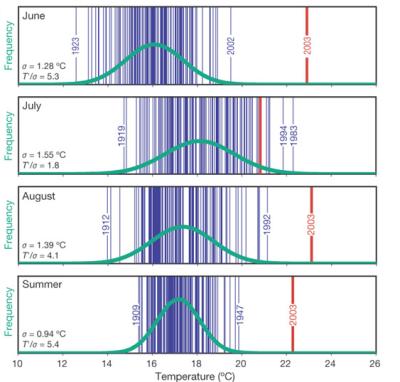

Those of you who lived through the summer of 2003 in Europe know it was what might be called, in statistical terms, "an outlier" - 20,000 dead'll do that. But it wasn't clear to me just how much of an outlier until I read this paper by Christoph Schär et al. in the Jan. 22 Nature.

The paper's a great example of the difference between the more conventional phrase, "global warming", and the more useful and accurate way of looking at things - "global climate change".

Schär and his colleagues looked at the statistics of how warm it had been, using a good long-term temperature time series from Switzerland – 12 sites with temperature records going back to 1864. In general, temperatures fall into what statisticians call a "normal distribution" - a lot of numbers on and around the average value with fewer and fewer cases the farther you get from the mean, an arrangement that creates the classic bell curve.

When the Swiss scientists plotted the summer of 2003 against the historical record, it showed up as being off-the-chart weird:

Those big bright lines on the right are most assuredly not "normal", in either the practical or the statistical definition of the word. Exactly how weird? Schär et al. estimate a return period, based on the old climatology, of 46,000 years, give or take a whole bunch. They're cautious about that statistic: "This large return period should not be overstated, and is here merely used to express the rareness of such an extreme summer with respect to the long-term instrumental series available."

So what's going on here? Well, clearly what happened last summer is more than just the whole graph getting pushed to the right because the whole place is getting a little bit warmer. What's really going on, they suggest, is an increase in variability. That means a wider dispersion from the mean of temperatures. That is exactly what the climate models predict, and that seems to be what happened in the summer of 2003.

Dontcha just love libraries? Nothing quite like the serendipity of finding something unexpected on the shelf next to the thing you were looking for.

On my mission to better understand statistics, I was at the downtown Albuquerque library Saturday going through all the stale, musty old stats textbooks when I stumbled up on Edward Tufte's Visual Display of Quantitative Information.

Tuft tells the story of John Snow, a London physician in the 1850s who removed the handle from the Broad Street pump and halted a cholera epidemic that had killed half a thousand.

He did it, Tufte argues, by making a map:

Deaths were marked by dots and, in addition, the area's elevent water pumps were located by crosses. Examining the scatter over the surface of the map, Snow observed that cholera occurred almost entirely among those who lived near (and drank from) the Broad Street pump.

Snow had the handle removed from the Broad Street pump, the cholera stopped, and epidemiological history was made.

I've heard the story before, and always loved it - the power of a simple idea, and a map. Only it turns out it's not true. Several years ago, a group of scholars went back through the record to figure out what Snow really had done and not done. The results of their work, published in The Lancet three years ago, show that Snow had been working for some time on the Cholera problem, and had suspected contaminated water as the cause based on a number of other outbreaks in London. In each case, they tended to be confined to users of a single water system, always one drawing from a part of the Thames contaminated with sewage. (This is one of those scientific ideas that seen like a "doh" today, but really required great insight at the time - remember they didn't really have a concept of "germs" yet.)

"The map" was one of a number he drew while working on the problem, and none grew out of a flash of inspiration, arising instead out of a lot of long hard work.

Snow's Broad Street cholera work is unquestionably a scientific tour-de-force, but it did not arise, as the myth would have it, out of sitting down in a single afternoon and drawing a map.

Doesn't change for a moment my thinking about Tufte's book, though. It's terrific.

From Geodog:

So I walked into the cafe tonight and looked around for the Joel group -- like any other geek, I was too shy to ask anyone, but when I spotted a big table lined entirely with males, mostly in their mid-twenties to early forties, not too well dressed, predominantly European-American, I knew that I had found the geek gathering.

(Link via Joel.)

I was talking to my daughter, Nora, and her friend, Andy, last night about snow days.

We all anecdotally remember the kids having a lot more snow days in the past, but it's been years - Andy said he's pretty sure at least four - since school here in Albuquerque's had to be cancelled because of a big storm. I need to track down the statistics to see if our memories are right.

Here's someone who has some related numbers:

Over the past decade, resorts across Europe have expressed increasing concern about the early melting of the snow cover. The Swiss Association of Winter Sports Resorts says that in the past 20 years the length of the season in the Swiss mountains has been shortened by 12 days due to the increase in temperature.In the French city of Grenoble, the Snow Research Centre said that a 1.8-degree increase in temperature in France would shorten the annual length of snow cover at above 1500 metres to 135 days from 170 (minus 20 percent) in the northern Alps, and to 90 days from 120 (minus 25 percent) in the southern Alps.

It's one of those fabulous examples of yet another huge world about which we know nothing: the realm of the symbiotic fungi living on the leaves of plants.

All plants seem to have 'em, but why are they there? They suck up a small amount of the plant's energy, and in the brutal economics of evolution, that which takes away resources must also contribute something, or it'll get whacked soon enough.

In last week's Nature, Keith Clay[1] explains a wonderful bit of experiment by Elizabeth Arnold of the University of Arizona and her colleagues on fungus living on the leaves of our beloved cacao, the plant that brings us chocolate.

What seems to be the best previous research into the issue (“the best-understood case”, Clay calls it) looked at tall fescue grass, which tends to be “infected”, as it were, with a fungus that starts in the seed but eventually infects the whole plant. The fungus produces a toxin that seems to tend to deter grazing animals. That's the benefit that provides the delicate balance need to keep the relationship teetering on the knife's edge of evolutionary survival. But the fescue is an odd case of what Clay calls “vertical transmission” - from seed to host plant. Most fungi seem to be transmitted “horizontally” - from full-grown plant to full-grown plant on the wind.

Arnold and her colleagues were trying to understand how the evolutionary relationship played out in such a horizontal transmission case.

Clay explains the problem thus:

Given that endophytes use their hosts' resources, they must entail some cost to the plant. If the costs outweigh the benefits, why don't plants defend themselves against infection? And if the benefits outweigh the costs, what are these fungi doing to help the plant?

Cacao's one of those plants that, in domestication, has been far removed from its natural setting. Today's agricultural use primarily happens in the Old World, despite the plant being a native of the Americas. That is because disease ravages the plant here.

Arnold et. al. played with Phytophthora, the organism responsible for an affliction in the cacao called “black pod disease”. They protected some cacao leaves from wind-borne “infection” with the symbiotic fungus, while some were allowed to grow normally. Turns out the cacao without the fungus were far more likely to die from black pod disease, suggesting the fungi are acting as a sort of bodyguard for their host.

Let's recall now my initial point about another huge world about which we know nothing. It seems as though essentially all plants have fungi growing on them. This is another enormous layer of complexity in the evolutionary/ecological story that has yet to be worked out.

We know so much, but we know so little.

[1] Clay, Keith, Fungi and the food of the gods, Nature, 427, 401 - 402 (29 Jan 2004)

From the "100 Years Ago" feature in today's Nature:

It may interest some to know that radium destroys vegetable matter. I happened to replace the usual mica plates, used to keep in the small quantity of radium in its ebonite box, with a piece of cambric, so as to permit the whole of the emanations to pass out, mica stopping the gamma rays. In four days the cambric was rotted away. I have replaced it now several times with the same result.

Hmmm. A clue.

I had occasion, in reading background material for a story on which I'm working, to make the acquaintance this week of J.C.R Licklider's remarkable 1960 essay Man-Computer Symbiosis. Given that he was peering out in our direction more than four decades ago, it is impressive to reflect today on how much he could see.

There is at once an embarrassing naiveté to Licklider's words, and a breathtaking sense of the possibility that he saw at a time when surely there was very little on which to base his vision:

The hope is that, in not too many years, human brains and computing machines will be coupled together very tightly, and that the resulting partnership will think as no human brain has ever thought and process data in a way not approached by the information-handling machines we know today.

One of Licklider's central insights comes from a little experiment he did on himself, measuring the time he spent on the various pieces of a "scientific and technical task". He found that he was spending 85 percent of what he called his "thinking" time spent in the drudgery of manipulating the representations of information on which he needed to act, rather than in the task of actually thinking about and acting on that information:

Much more time went into finding or obtaining information than into digesting it. Hours went into the plotting of graphs, and other hours into instructing an assistant how to plot. When the graphs were finished, the relations were obvious at once, but the plotting had to be done in order to make them so. At one point, it was necessary to compare six experimental determinations of a function relating speech-intelligibility to speech-to-noise ratio. No two experimenters had used the same definition or measure of speech-to-noise ratio. Several hours of calculating were required to get the data into comparable form. When they were in comparable form, it took only a few seconds to determine what I needed to know.

Licklider's "thinking time", he realized, was largely devoted to the mechanical rather than the insightful. "Moreover, my choices of what to attempt and what not to attempt were determined to an embarrassingly great extent by considerations of clerical feasibility, not intellectual capability." What if computers could be made to handle those mechanical details, freeing him for the intuitive and insightful bits that are uniquely human?

There is here a point where the glass through which Licklider was looking was entirely too dark. He was imagining a computational world in which we learned how to give our machines the flexibility to deal with the myriad varieties of those clerical tasks:

Severe problems are posed by the fact that these operations have to be performed upon diverse variables and in unforeseen and continually changing sequences. If those problems can be solved in such a way as to create a symbiotic relation between a man and a fast information-retrieval and data-processing machine, however, it seems evident that the cooperative interaction would greatly improve the thinking process.

That, we have come to realize, was an impossible goal, so we have instead learned to bend the clerical tasks around the rigid constraints of the software we are able to write. But we have nevertheless been able to write software and build computers that have become useful assistants.

Chris Mooney was at yesterday's Congressional hearing on what is now euphemistically being called in Washington "sound science":

The House Committee on Resources' "sound science" hearing I attended yesterday represented, in my view, a fairly stunning attempt by Republican legislators to cast themselves as the party of "science," while pushing proposals that would actually deemphasize science conducted by federal agencies while privileging scientific claims coming from the private sector.

I'm looking for suggestions on a good statistics book.

For my book project, it's becoming clear that I need a deeper understanding of the statistical issues associated with climate research. Many of the data sets used are easily publicly available, so it makes sense to deepen my understanding by actual playing with the number myself. But to do that, I need a better understanding of the statistical tools.

I'm getting some help already from a volunteer "statistics coach", a friend who's a physician with a highly developed interest in the statistical problems of the practice of medicine. He's loaned me his copy of Stanton Glantz's Primer of Biostatistics, which seems promising. Its focus is on medicine, but much of it seems completely generalizable.

I'm looking at something that is pitched at undergraduates, ideally with a lot of practical examples/problems on which I can practice. As a bonus, a book with an on-line component would be great - downloadable data to play with.

Suggestions?

I love it when the pundits are wrong:

Several reports these last few days have noted that Howard Dean had bagged about 8,000 absentee votes in New Mexico prior to his post-Iowa tailspin. This in itself should have made him competitive in New Mexico, since, as most of these reports went on to suggest, only about 50,000 people were expected to vote in today's state-wide caucuses. In fact, combine the 15 percent of the likely vote Dean's cache of absentee ballots gives him with the 15 percent support he garnered in the final New Mexico poll, and he's basically in the same place, 30 percent, John Kerry is (at least according to the same poll).But now come reports that there's a major snow storm headed toward New Mexico (and the Albuquerque/Santa Fe population hub in particular) this evening. If the storm pushes turnout significantly lower than the expected 50,000, it doesn't seem like a stretch to think Dean could actually carry the state by a relatively comfortable margin.

(Never mind that his arithmetic is flat wrong, that Dean's alleged 8,000 absentee votes plus 15 percent of the number Scheiber uses above gives him must 23.5 percent of the vote. That really doesn't matter. He could have just waited a couple of hours to see what actually happened, rather than predicting the future, badly. What's the rush?)

My book review of 100 Suns.

That's the "Mike" shot, the first hydrogen bomb - arguably a very important moment in history.

The L.A. Times' David Shaw has one word for journalists tempted to predict the future - don't:

When a political reporter is trying to analyze what happened and why and what it means in a caucus or a primary election, it can be difficult to resist the inclination to apply those lessons to the next primary and predict its outcome — and to persuade oneself that this is what readers and viewers want. After all, astrology columns wouldn't be so popular if readers weren't interested in what some presumed expert thinks will happen next.But journalists aren't — shouldn't be — astrologists. When political journalists predict the future, their predictions often seem to eclipse — and at times substitute for — the reporting they're supposed to be based on. Worse, those predictions can become self-fulfilling prophesies.

His case in point: the ad nauseum analysis of the Dean Scream. I'm with David on this one:

I didn't find that speech, or the accompanying scream, all that alarming. In fact, I thought the coverage of the speech was far more hysterical than the speech itself. To me, Dean was trying to comfort and encourage his tired, disappointed troops. It was like a pep rally after the home team had been crushed in a game it had once been heavily favored to win. Dean knew there was another big game the next week, and he was trying to rekindle his supporters' enthusiasm and commitment.But his comments, and his yelp, were played hundreds of times on television, mixed and remixed into virtual wallpaper in the political and cultural blogosphere. Dean's candidacy, everyone said, was now doomed.

As the Washington Post put it, "Dean may have blown up his presidential aspirations Monday night with that address ….:

It was the media echo chamber's explanation of what The Scream should mean to us, rather than The Scream itself, that became the reality.

QED.

From this morning's Albuquerque Journal:

The Bush administration asked Congress on Monday for the largest nuclear weapons budget in U.S. history.The Bush administration's request of $6.9 billion for nuclear weapons work is larger, in inflation-adjusted terms, than the budget reached in 1985 during the peak of the Reagan administration Cold War. That was the previous largest U.S. nuclear weapons budget, according to a Brookings Institution study of U.S. nuclear weapons spending.

My friend and competitor Ian Hoffman did a much better job of sorting out the details:

The Bush administration wants more money for nuclear weapons in 2005, including studies of new or modified hydrogen bombs and, if called upon, the means to conduct nuclear tests faster.In a year of cutbacks or meager growth for most domestic agencies, the White House is seeking a 5.4 percent increase for the weap-ons arm of the U.S. Energy Department, to $6.6 billion.

Despite bipartisan criticism among House lawmakers last year, the National Nuclear Security Administration signaled Monday that it is asking for more money across-the-board in the modestly expensive, but controversial programs aimed at new and modified H-bomb designs.

An unusual coalition of GOP budget hawks and Democrats gutted several of those programs last year, cutting in half requests for speeding nuclear testing, if ordered by the president, and for a massive nuclear "bunker buster" known as the Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator.

In the case of the bunker buster, the administration was forced to shut down work on one of two competing nuclear-weapons designs and devote all of its bunker-buster research to a single bomb, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory's B-83.

Now the Bush administration is reviving both ideas, seeking a 25 percent increase in test readiness, to $30 million, and a more than 200 percent increase for the penetrator, to $27 million.

"They're coming back in and trying to recover their losses," said David Culp, legislative liaison for the Friends' Committee on National Legislation, a Quaker group that monitors nuclear arms issues. "I think that's going to get pretty tough scrutiny from Congress."

I received a piece of spam today from Carson Marks. At first I thought, "Wow, a veteran of the Manhattan Project, one of the designers of the first atomic bomb, is trying to sell me prescription medicine on line." Then I realized the eminent theoretical physicist is J. Carson Mark, not Marks. Plus, the eminent theoretical physicist is dead, so how could he be hawking on-line drugs?

David over at Quark Soup yesterday linked to a fascinating excerpt from Lauren Slater's new book Opening Skinner's Box. Slater is the woman who wrote Prozac Diary. She's a psychologist who has suffered mental illness herself. She's also a terrific writer, her stuff so raw that at times it's uncomfortable to read. In the piece excerpted in the Guardian, she talks about a famous 1972 experiment in which eight sane people feign mental illness to get themselves admitted to psychiatric hospitals. Slater repeats the experiment. It's riveting to see how the system handles her trickery today.

Fortune magazine (no bastion of liberal thinking, mind you) weighs in on the question of abrupt climate change with a tidy little explanation of the potential for the thermohaline circulation to abruptly change:

Scientists still don't know whether a climate disaster is on the way. But taken together, these changes appear strikingly similar to ones that preceded abrupt climate shifts in the past. Many researchers now believe the salient question about such change is not "Could it happen?" but "When?"

It's important to note the language here. We're really tallking about "global climate change", not "warming". Big and important difference.

I found the answer this morning to one of life's great mysteries.

In my Inkstain logs, I see a steady traffic to an old blog entry about Lowell George and Frank Zappa, and I've never understood why. I only found one person linking to it, an entry from back in December on a rarely updated blog. Could that be it?

But I had underestimated my own Googlejuice. This is my own doing. Enter don't bogart that joint into Google, and my old blog entry ranks number one. I own "don't Bogart that joint". Nine or ten times a day, it seems as though someone somewhere on the planet is typing "don't Bogart that joint" into Google and reading my blog. Truly remarkable.

A package arrived recently from my sister.

It included a copy of "I Ripped My Pants". While at the beach, Spongebob sees weightlifters looking buff and tries to show off, with hilarious results. I don't want to give away the ending, but let's just say the title offers something of a clue.

It includes "An Ocean of Tattoos" ("Kids: Ask an Adult to Help You." - always good advice).

I knew I was in trouble when we hit the bottom of the hill out of Corrales.

It was hellaciously windy day, so we'd dropped down into the valley for some protection. But there reaches a point where you run out of valley. We were about 90 minutes into the ride, and I'd been hanging on for dear life most of the way, trying to hold onto someone's back wheel. Once I lost it and got out into the wind, it was hell to get back on, and the guys I was riding with are pretty fast.

They'd always stop and wait, mind you, but you don't want that - distinctly not macho.

Corrales is a little rural village on the edge of Albuquerque, cottonwoods along the river valley bottom. There's a back road through town that's big and wide, with a bike lane most of the way, but at the end you end up out on Corrales road, which is narrow and busy, so we were in a single line. I, of course, as had been the case for most of the day, was last.

Corrales Road at the north end of town winds left and kicks up into a little hill out of town. It's not a long hill, but it's become something of a badge of honor to bust out a good, quick climb before we stop in the gas station parking lot at the top to regroup. This is the hill that Jaime once raced a front-end loader going up. Jaime won.

I was sitting on the back (note the above reference to "hanging on for dear life"), and I could see Jaime getting itchy, slipping out to the left a little, looking for a chance to jump. When he he hit it, I made a vague attempt to get on his back wheel, but who was I kidding? I looked down at my heart monitor, saw it hit the red line, and shut it down.

That's the way it went from then on. We'd be climbing these hills into the wind – not big hills, but the wind made them big – and I'd try to go with them, and they'd end up waiting for me at the top.

It was a pretty humbling ride, one of the hardest I've ever done. But when we finally hit the top ("top" defined here both in terms of altitude and wind gradient) and made the turn for home, we were flying! For one stretch, a favorite road that rolls across the open desert west of town with the panorama of the Sandia Mountains to the east and our city laid out at their foot, I led the train. I enjoyed that very much.

Science writers like to make hay when scientists see something that's, ya know, never been seen before by humans and stuff. But this (NYT, reg. req.) is about as genuinely "never been seen before" as it gets: two new elements, 115 and 113 (nominally "Ununtrium and Ununpentium" for now) created in a lab in Russia. 113 is especially what the physicists would describe as "long-lived", and by that they mean a second. Blip. We'll not be building furniture out of that one. But they do seem to exist on what Kenton J. Moody, one of the scientists involved in the experiment described as "the shoals of the island of stability," an area where physicists theorize that stuff will live a bit longer.