Plannning a long ride tomorrow with Jaime and some of his tri friends, and it just occurred to me that the subject of missing the Super Bowl never even came up. (Sorry, jrb, I'll be rooting for the New England Whatevers on your behalf while we're out doin' the thing.)

Today's Global Climate Update comes from the icy city of St. Petersburg (you may remember it fondly as Leningrad), where folks are apparently worrying now that they might be swimming in the cold waters of the Gulf of Finland:

St. Petersburg may have the same fate as the fairy-tale city of Kitezh that was completely covered with water.St. Petersburg as many other coastal European cities may be faced with the threat of complete or partial inundation in the next 20-30 years, oceanologist and geologists Alexander Gorodnitsky, who was born in the city and lived there for 40 years, said in an interview with Itar-Tass.

The global warming may begin melting ice in the Arctic, and it will considerably raise the ocean level.

This of course runs counter to the conventional geopolitical opinion that the Russians are not all that enthusiastic about curbing their greenhouse gas emissions, because they rather think they would benefit if things got a bit warmer. Does anyone know if that conventional wisdom is true?

Dan Gillmor says he's considering turning off comments on his blog because of comment spam. Further evidence of the damage a small group of the amoral can do to the commons.

More stuff I wrote elsewhere:

Houck's disquisition does beg an important question, which is what policymakers should do in the face of genuine uncertainty. Greenhouse-induced climate change is a case in point. While there seems little scientific doubt that we're changing our climate, the details of how that climate change will play out are hugely uncertain, as are the effects on the climate system of various greenhouse-gas mitigation strategies.So what's a policymaker to do? It's a legitimately hard problem.

From PEZCycling's interview with George Hincapie:

PEZ: Can you palm a basketball?George: Aah, yeah…?

A genuine emacs vs. vi flame war erupted today on the New Mexico Linux Users Group mailing list. That's such a standing joke that I never could have imagined it actually happening.

So far no references to Hitler.

I haven't been fixing many GNOME bugs lately, but when jrb files a bug, I feel honor bound to jump to it. (Well, if it's something I can fix in five minutes, anyway. If it'd taken any longer I would have just shifted responsibility by cc'ing someone else on the big and absolving myself of any guilt.)

Rummaging through Henri Grissino-Mayer’s dendrochronology web site this evening I ran across the remarkable story of Antonio Stradivari and the Maunder Minimum.

I know Grissino-Mayer through his climate research. While at the University of Arizona in the 1990s, he did the first millennial-scale tree ring climate record for New Mexico, and he's been a wonderfully helpful source for me for years on dendro and climate issues. I was looking for a new paper of his on drought in the Pacific Northwest when I found his little piece of scientific candy about Stradivari and the Maunder Minimum.

Named after solar astronomer E.W. Maunder, the Maunder Minimum is a period from the mid-1600s to the early 1700s when sunspot activity dropped dramatically. Records are spotty from back then, but researchers who have put together analyses based on observers who were keeping records at the time suggest something odd happening on the sun.

I've been reading about it because it's one of the first things that proto-paleoclimate people looked for when they began assembling the first tree ring records in the early 20th century. (They found it.)

Grissino-Mayer and colleague Lloyd Burckle took that tree ring record and applied it to the unlikely field of the history of music. People have long puzzled over the apparent mastery of the late 17th-early-18th century violin makers. Why do they sound so sweet? Grissino-Mayer and Burckle think it may be the wood. Reduced solar activity, we know, led to longer winters and cooler summers. That meant trees with slow, even growth:

During Stradivari's latter decades, he used spruce wood that had grown mostly during the Maunder Minimum. These lowered temperatures, combined with the environmental setting (i. e., topography, elevation, and soil conditions) of the forest stands from where the spruce wood was obtained, produced unique wood properties and superior sound quality. This combination of climate and environmental properties has not occurred since Stradivari's "Golden Period."

There's a great line in one of John McPhee's geology books about what it's like riding in a car with a geologist distracted by road cuts. The idea is that road cuts lay bare the rocks, the geologist is always looking at the side of the road rather than paying attention to driving, etc.

Opportunity seems to have landed in a road cut.

Pretty much every cyclist I passed today on my ride along the riverside trail had the same silly grin on their face, a cross between "Jeez this is fun" and "You're as much of a fucking idiot as I am." Something about the shared adventure....

The weather was snarky, spitting a mix of snow and rain that got progressively thicker the longer I was out. The weather had what the meteorolgists call "energy", showers popping up here and there all morning all over the valley, spitting in my face at least half the time, until the trail was wet and my tires were hissing, sending up rooster tails. Usually I stay in on a day like today, but I've been cooped up with a stiff neck for, like, a week or more, and I'm finally feeling good, and I've spent all this money on high-tech clothes, damnit, I'm gonna ride!

Note to self: try the plastic bags around the socks trick next time. My feet about fell off, they got so cold after the water got through my shoes. But the rest of the high-tech clothing performed admirably. Must give bike a bath, though.

With further assistance from Hallski, my RSS feed now should have a "read more" liink for those really long posts.

This isn't one of those really long posts, but I need to test it to be sure it works.

I see on Footnotes that a new free software package, LiarLiar, has been released that claims to use "Voiice Stress Analysis" to detect lying. The blurb is carefully written to suggest that it's something short of a lie detector - "Stress can be one indicator of whether or not a person is being truthful in the statements and communcations that he or she is making." But the screenshots and the app's name are clear - this is a lie detector. And it's pretty clear that lie detectors in general just plain don't work. It's pseudoscience.

In particular, according to a review by the National Academy, there's no good evidence that voice stress analysis works to detect deception. As with polygraphs, that means that the problem of false positives (people wrongully accused) and false negatives (people getting away with lying) will swamp any actual usefulness the tool can offer. To the extent that people actually believe what the software is telling them (and why else would you use it?) this clearly could do more harm than good.

There was a joke I read somewhere about the dorky appearance of a cyclist in tights varying with the square of the distance from the bike. Yeah, that seems about right. And the baseball bat doesn't help.

I missed this paper (Nature, subscription required) when it came out last month. It's pretty interesting. Ruth Curry, from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and her colleagues measured changes in salt and fresh water in the Atlantic:

The oceans are a global reservoir and redistribution agent for several important constituents of the Earth's climate system, among them heat, fresh water and carbon dioxide. Whereas these constituents are actively exchanged with the atmosphere, salt is a component that is approximately conserved in the ocean. The distribution of salinity in the ocean is widely measured, and can therefore be used to diagnose rates of surface freshwater fluxes, freshwater transport and local ocean mixing - important components of climate dynamics. Here we present a comparison of salinities on a long transect (50 S to 60 N) through the western basins of the Atlantic Ocean between the 1950s and the 1990s. We find systematic freshening at both poleward ends contrasted with large increases of salinity pervading the upper water column at low latitudes. Our results extend a growing body of evidence indicating that shifts in the oceanic distribution of fresh and saline waters are occurring worldwide in ways that suggest links to global warming and possible changes in the hydrologic cycle of the Earth.

That's a bit dense, but there's a "holy shit" buried in there for those of you in Britain and elsewhere in Europe. Y'all are being warmed by a big-ass current flowing up the Atlantic, bringing warm water from the tropics. The "Wally Broecker hypothesis" is that global climate change caused by greenhouse gases could cause the conveyor belt to shut down. Bingo. European ice.

Geoffrey Lean, in The Independent, gives an altogether too breathless take on Curry's work:

Britain is likely to be plunged into an ice age within our lifetime by global warming, new research suggests.

"Likely" seems all too strong a word, if my understanding of the science is correct, but "strong possibility", especially given Curry's apparent empirical support for Broecker's hypothesis, doesn't seem far from the mark.

Another library gem:

That's from the 1914 book "The Climatic Factor As Illustrated in Arid America". The analysis that goes with the graph seems, with our centuries' worth of hindsight, a bit naive. The argument is that when it rains too much in Europe, crops fail, so people move to America. The link between climate and human culture is more complicated than the graph's neat correlation would indicate. But what's so amazing is not that the author was simplistically wrong, but that he was posing these great, penetrating questions that rightly supposed that the climate-culture link would be huge and important and worth our time.

I found a little gem in the library this afternoon in Isis, a journal "devoted to the History of Science and its Cultural Influences". My old college mentor Joe Maier introduced me to Isis, so it felt a little nostalgic pawing through its pages.

What interested me was a little trifle published in the back pages of the December 1945 issue entitled "When was tree-ring analysis discovered."[1]

I've been following back footnotes from George Webb’s scientific biography of A.E. Douglass[2], and Webb mentions the marvelous factoid that it was Leonardo (What was it an old colleague used to say? "Great story. Better if true.") who first suggested the possibility that tree rings could be used for the study of climate.

(Click through to read the rest, it's really long.)

Webb’s source for the assertion is the little Isis trifle, a brief disquisition by George Sarton, dean of the historians of science, on the question of the “discovery” of the science of tree rings.

Sarton doesn’t question the primacy of my guy Douglass, who essentially invented the science of dendrochronology in the first few decades of the 20th century. A couple of 19th century researchers, Twining and Kuechler, had worked on the problem of crossdating between trees, but it was really Douglass who put it all together. But well before that, Sarton finds a number of antecedents. “It appears,” Sarton writes, “that in this case as in so many others the discoverer was Leonardo da Vinci.”

Leonardo observed the tree rings and recognized in them indications of weather and age; he noticed the differences obtaining between the northern and southern exposures of each tree (the rings are broader on the north side, and hence the center of the section is closer to the south side).

Sarton also quotes a delightful account by Michel de Montaigne, who traveled in Italy in 1580-1581 (this would be about a century after Leonardo). In his diary (translated by Sarton from the Italian in which Montaigne wrote it), the traveler describes a meeting with an Italian craftsman who seemed to have the tree ring thing all figured out:

The artist, a clever man, famous for his ability to make mathematical instruments, taught me that every tree has inside as many circles and turns (cerchi e giri) as it has years. He caused me to see it in many kinds of wood which he had in his shop, for he is a carpenter. The part of the wood turned to the North is the straightest, and the circles there are closer together than in the other parts. Therefore when a piece of timber is brought to him he is able, he claims, to tell the age of the tree and its situation (the orientation of the section).

Sarton also offers a tantalizing suggestion, though not well documented, that the ancient Greek Theophrastos had a go at the tree ring thing as well. “It is probable,” Sarton quotes another scientist, Waldo Glock, as writing, “that the use of tree rings for dating purposes has been rediscovered several times in the last 2,000 years or more.”

1. Sarton, G., When was tree-ring analysis discovered. Isis, 1954. 45(4): p. 383-384.

2. Webb, G.E., Tree rings and telescopes : the scientific career of A.E. Douglass. 1983, Tucson, Ariz.: University of Arizona Press. xiii, 242 p.

Prodded by Glynn and aided by the fact that Dave Camp was smart enough to write it down and publish it when he figured out how to do it, I changed my RSS feed so the whole entry now shows up, meaning the whole entry is now published on the planet. This is a good thing, except that lately I've been rather blathering on with some very lengthy posts (I'm using the blog to work out ideas), and I don't want to bore folks unnecessarily. So my idea is to figure out how to make stuff in the "read more" MT bit (additional entry text, I believe it's called) not show up in the RSS feed. Here's a test to see if this works.

Here's some more stuff that's in the "additional entry text" section of my blog entry. The test is to see whether this shows up on the RSS feed (and therefore on Planet GNOME).

I returned from a meeting out of the office today to find two bananas on my desk. One had a sticker on it suggesting that fresh fruit can reduce my risk of cancer. Seemed reasonable, so I ate the banana.

An interesting new group has emerged in Ohio: the Unintelligent Design Network: "Although life was designed by an all-powerful creator, he is in reality pretty dumb and not very good at it. "

(From Dave Thomas.)

I'm not a political journalist, so maybe it's a little bit easier for me to make fun of the whole process without feeling too much shame or accountability. But I sure am enjoying Joshua Micah Marshall giving voice to the vague discomfort he feels at the way the thing is done. This morning it was the bizarre way in which one covers the Democratic debate "in person" by watching it on a big-screen TV with a bunch of other journalists. Why not just stay in your hotel and watch it on TV there?

Seeing it in person would certainly add something to one’s reportage. But you never see it in person. Generally how it works is this: You’re in a big complex and there’s one large hall set aside for the actual debate. In that room you have the candidates, a few of their handlers, the moderator/questioners and the audience. Oftentimes you’ll have a tiny handful of journalists there too --- but only ones from the highest echelon of the elect. Maybe a Koppel or a Mitchell --- folks like that.Everyone else is in a big room somewhere nearby with a bunch of long school room tables arranged as they might be for an SAT test in high school. And space after space at those tables is occupied by journalists with laptops open, a phone at each station, perhaps some other paraphernalia nearby or a parka, watching the debate on a series of big TVs.

In other words, they’re watching the debate on TV just like you are. Only they’re doing it in a big room with all the other journalists.

Now, this can be kind of fun, because you get to see a lot of other people you know, and a number you haven’t seen in a while. And you get a very good sense of how other reporters think everybody did. But that can be a pretty skewed view, an echo chamber in the making in ways you can probably imagine, even if you don’t spend much time talking to the really egregious above-it-all conventional wisdom types.

Something I wrote elsewhere, in which I invoke the work of the incredibly interesting Roger Pielke Jr..

Seth Nickell on bad ATM user interfaces:

Despite the fact that most ATMs only handle money in multiples of $20, they still require you to enter the "cents". So asking for $40 entails the button sequence 4-0-0-0. I almost always withdraw $40, so I perform this series of presses without a lot of higher brain involvement. Unfortunately, this ATM fixed a "bug" in the way 95% ATMs work: they only let you enter whole dollar values.

The ATM's I've been using say on screen, at the end of the transaction - "Be sure to take all bills."

Is this a problem? I can understand Seth's rather comical tale of losing his card, but do people regularly forget to take their money?

Developer's wisdom:

It felt quite therapeutic to write docs. I should do this more often.

The Journal sent me to the Albuquerque City Council meeting last night. This is representative democracy at the very retail level. It was a hoot.

There was a time in my career where I spent many a night covering the pageant, from the Walla Walla city council meetings and the school board, to Pasadena. In many ways it was what first drew me to the business. Reporters love to whine about having to cover government meetings (and I whined too, of course), but deep down I have always loved them.

Here's why.

At last night's meeting there were a bunch of people from the arts community, pitching for a new sliver of sales tax. The conductor of the symphony spoke, and a buddy of mine who tries to make movies for a living.

There was a group of guards from the jail, with their wives and husbands and little baby boys and girls, there to ask the council for some sort of improvement in their health care benefits.

There were anti-nuclear activists concerned about radioactive waste (that's why I was there). And to counter them, some technical types who think the waste in question is safe.

And there was this, uh, interesting woman who spoke on pretty much every issue before the council, tieing them all to the illegitimacy of the federal government and the true righteousness of the Free Republic (I'm a little unclear on the details here, the Freemasons are also somehow involved, she was a bit hard to follow).

Everyone got to say their piece, and the council gave some what they wanted and disagreed with others, but it was all passionate and genuine and so very face-to-face.

Today being the day of St. Agnes, we are apparently supposed to put pee in our shoes. Or something. I'm a little unclear on this one.

Agnes was just 13 years old back in the day when (as the Book of Days puts it) "she sang hymns while the executioner was hacking at her neck". Sweet girl, with some fortitude that apparently did not sit well with the Romans. As a result, she's the patron saint of girls, and here's where the pee comes in:

On St Agnes Day. Take a Sprigg of Rosemary, and another of Time, sprinkle them with Urine thrice; and in the Evening of this Day, put one into one Shooe, and the other into the other; place your Shooes on each side of your Beads-head, and going to Bed, say softly to your self: St. Agnes, that's to Lover's kind, Come ease the Troubles of my Mind. Then take your Rest, having said your Prayers; when you are asleep, you will dream of your Lover, and fancy you hear him talk to you of Love.

- Aristotle's Last Legacy

You go first. Really, I'll do it too, but you go first, OK?

A friend the other day was trying to tell me the story of Victor Frisbee, and sent me this. Reading down, I realized - to my amazement - that I was in it.

For those not on the GNOME foundation list, some mischief courtesy George. (I quote in its entirety for maximum effect.)

On Wed, Jan 21, 2004 at 12:27:36AM +0000, Alan Cox wrote:

> On Maw, 2004-01-20 at 15:31, Richard Stallman wrote:

> > In connection with GNOME, please remember to speak of it as

> > "free software", and to call the system "GNU/Linux". Many people

>

> With respect to the use of the term GNU/Linux please use Linux with the

> (TM) or the trademark symbol in situations where it might otherwise

> imply things like ownership (eg GNU/), otherwise it may lead to

> misleading assumptions about the Linux nameBut that could lead to an ambiguity as in GNU/Linux(TM), which can mean two

things, GNU / Linux(TM) or GNU/Linux (TM). Perhaps we need to add a set of

parenthesis as in: GNU/[Linux(TM)]. The notation is also confusing as the

system is really the natural homomorphism from GNU to GNU/[Linux(TM)] (then

[Linux(TM)] is of course the kernel of this homomorphism). And so

GNU/[Linux(TM)] is rather what you get after you apply the whole operating

system to GNU. To avoid this further ambiguity I think the entire system

should be called (using LaTeX as ascii is now deficient)\phi : GNU \rightarrow GNU/[Linux(TM)]

When one wants to purely refer to Linux(TM) as the kernel, we can shorten

this by just \ker(\phi), which is 1 letter longer, but only in ascii. When

printed it actually comes out as 6 characters as opposed to 9 in Linux(TM).

George continues, but you get the point....

Joshua Micah Marshal has a too-true account in his blog last night about the strange rituals of journalism - the asking of questions unanswered, the spouting of answers that are not, the iteration of that which must be said. He's in the Clark campaign headquarters and a bunch of A-list journalists (Joshua, must you be such a name-dropper?) are quizzing Eli Segal, the general's campaign manager:

These little chat sessions are classic moments of campaign kabuki theater. We’re asking Segal questions. But we’re not really asking questions --- as in asking questions in the sense that we think we’re going to hear what he thinks.What we’re doing is tossing out questions so that Segal can tell us what the campaign’s spin is. Everybody has a wink in their eye because everyone knows what the deal is.

It's not a bad thing, not a good thing, it just is what it is.

The Boston Globe has an interesting story this morning on some of the wackier ideas for combating global warming:

Technical fixes like filling the stratosphere with billions of silver balloons to reflect the sun's rays, or spraying the oceans with iron to make them suck up the gases causing global warming, should be developed as a safety net, they said. Some even felt the technology should be adopted regardless of need, because it would create a better world in which we could twiddle with the planet's temperature like a domestic thermostat.

The fear, cited by several of the scientists quoted in the story, is that providing such solutions might give politicians the excuse to not grapple with the underlying issue of greenhouse gas emissions.

The article also quotes a great line from David King, the UK's "chief scientific advisor to H.M. Government" (I love that title). In the Jan. 9 issue of Science (here, really expensive subscription required), King uses a trick I've used a bunch of times - comparing the problem at hand (in this case global climate change) to the terrorist threat:

Last year, Europe experienced an unprecedented heat wave, France alone bearing around 15,000 excess or premature fatalities as a consequence. Although this was clearly an extreme event, when average temperatures are rising, extreme temperature events become more frequent and more serious. In my view, climate change is the most severe problem that we are facing today--more serious even than the threat of terrorism.

King goes on at length about the threat to coastal humanity, and quotes a statistic that is apparently of great interest to Londoners:

In Britain, usage of the Thames Barrier, which protects London from flooding down the Thames Estuary, has increased from less than once a year in the 1980s to an average of more than six times a year.... This is a clear measure of increased frequency of high storm surges around North Sea coasts, combined with high flood levels in the River Thames.

If the flood barrier is breached, King wrote, the damage would be equivalent to some 2 percent of the current U.K. gross domestic product. He uses this by way of arguing that the economic costs of greenhouse gas reduction measures are reasonable relative to the cost of damage caused by global climate change.

In the Boston Globe story, King sounds the caution about those wacky alternative mitigation measures:

"I am in favor of having every weapon at our disposal to fight climate change. My only reservation is that you might provide a fig leaf for those who say we don't have to bother to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases. That still has to be the first priority."

For my friends and family in the deep freeze back east (Looks like you're in a warming trend! Above freezing today at Groton, down the river from my sister's house!) I'll point out that the thermometer on my back porch reads 56.8 and I'm wearing shorts this afternoon.

update, early evening OK, that was a bit of a cheat, and I knew it. My backyard thermometer reads high, the official high was just 51. But I really was wearing shorts.

I've added Chris Mooney's blog to my blogroll. He does some great stuff on the intersection of science and the public policy process, a subject of great interest to me, and does a regular column for CSICOP (an organization near and dear to me). Check out this, on OMB's new peer review proposal.

The issue of climate change sure looks different depending on which side of the ocean one is on. While we're busy over on this side of the pond making fun of Al Gore for even talking about global warming on a chilly day, over in Scotland they're taking it as a given and trying to do something about it:

With increased risk of flood, drought, storms and polar ice melt, trading emissions between individual companies in EU countries is expected to play a major role in helping to slow down the crisis.

The whole "humans on Mars thing" seems to preclude continued maintenance for the Hubble. What did I say about the one thing the shuttle was good for? Servicing the HST? Whatever.

Consider this shocking statistic, courtesy of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies:

Lack of health insurance causes roughly 18,000 unnecessary deaths every year in the United States.

Let's think closely about that number. In their best year, terrorists killed 3,000 of us. It caused a national paroxysm that continues today. Surely the death of 18,000 people per year is a tragedy of greater proportion?

But perhaps 18,000 is too large a number to be meaningful. Perhaps one is better, so consider the story of Virginia Heineman.

Chronically ill, and as a result chronically underemployed, Ginnie was one of those people who lived on society's margins. The medical details of Ginnie's death remain somewhat murky, but she was found in a rocking chair in her California desert home surrounded by used-up asthma inhalers. For much of the time that I knew her, she struggled to breathe, and it seems almost certain that that struggle is what finally killed her. She also struggled to find health care, drifting in and out of the system of hospital emergency rooms and unpaid bills that is the fate of the uninsured ill.

Although America leads the world in spending on health care, it is the only wealthy, industrialized nation that does not ensure that all citizens have coverage.

It is reasonable to think that if Ginnie - my wife Lissa's beloved sister - had access to consistent health care, she would be alive today, and would be a productive member of society. We miss her very much.

Spencer Weart at the American Institute of Physics has written a new book on the history of the science of climate change and has, along with it, produced an encyclopedic web compendium on the subject. Waaaay hypertext.

My rather imprecise discussion earlier of space science left some people with the impression that I was speaking in support of President Bush's Moon-Mars initiative. Nothing could be further from my feelings on this issue.

First, there is, in fact, no Bush initiative. This is words, not deeds, and the deeds will be interesting and worthy of debate at some future point, but the words are just hot nothings. Doing something of this sort takes money and a plan, and the Bush Adminstration has offered neither. So perhaps this is best ignored. But the idea, as vaporous as it is, is at least in play, and therefore is worth addressing.

For a number of decades we have been flying astronauts round and round in low earth orbit. There has been a scientific fig leaf of microgravity experiments and the like, but the only real justifiable research one could argue that we have been conducting was self-referential - sending humans into space to learn about sending humans into space. And what is it that we have learned? That it is expensive, dangerous, and not terribly useful. In short, if we have learned anything, we have learned that sending humans into space is, at least as we understand today how we might do it, a bad idea.

During that same time, we have launched unmanned probes to Venus, Mars and the gas giants that have returned a trove of amazing and useful scientific data. Compare and contrast.

The program's defenders point to the unique skills a human in space offers that a robotic probe lacks. Look, they say, at the remarkable Hubble servicing missions, which could not have been done by a robotic satellite. I grant that this is true, but ask at what cost? For the money we've spent on shuttle flights, we could have lobbed up a new Hubble once a year. So what if one of them, or two or five breaks. We'd have a whole bunch more!

There's a great story often retold here in the high desert country of the U.S. southwest about Garcia Lopez de Cardenas, the first European to see the Grand Canyon. It was 1540, and he and his party were hunting for the fabled lost cities of gold. We see the great canyon for its majesty and intrinsic beauty. For Cardenas, it was in the way. His reaction, in essence, was, "Crap, guess we can't go that way." The retelling of the Cardenas story is usually accompanied by a sort of mockery. "What a fool, could he not see?" But I think that misses the point. There was a time three centuries later when technology and the need of this continent's European immigrants had reached the point where the canyon made a different sort of sense. And today, with tough rubber-skinned inflatable boats, radios and the prospect of helicopter rescue, and our post-20th century aesthetic, it makes perfect sense. But I await the making of that case with respect to Mars.

Drawn like a moth to flame, I could not resist this morning reading the Associated Press account of the truly bizarre appearance yesterday of celebrity musical entertainer Michael Jackson in a California courtroom. As is my rule, my penance has been to search out two important stories about far away places and issues about which I would normally not be likely to read.

One: The Cost of AIDS Tests (reg. req.)

Five big drug companies yesterday announced a deal to cut the costs charged in the developing world for a key test used to calibrate AIDS treatment. The AIDS death toll worldwide makes pretty much any problem we could imagine - drunk driving? terrorist attacks here? Saddam's chambers of torture and death? famine? - look like chlid's play.

Two: polio (reg. req.)

When's the last time you heard talk about polio? Me too. Turns out that the disease, while largely eliminted from the industrialized west and on the wane everywhere, has undergone a bit of a resurgence in recent years, and there's a concerted effort in a number of places - Afghanistan, Egypt, India, Niger, Nigeria and Pakistan in particular - to whack it back down.

Hunger

My perhaps overly glib defense of NASA’s Mars rover missions drew a couple of good challenges worth addressing. Adrian Custer challenged my assertion that the $820 million NASA’s spending on Mars is “chump change.”

On the world hunger question, jfleck is wrong that $820 million is chump change. If you look at the whole budget for applied research in agricultural sciences it's not very big. Take the next rover mission, move it to agricultural research and you might very well find ways to increase agricultural productivity in africa by a few percentage points. Doesn't even really need research, more of a question of paying for outreach. And a million bucks pays for a whole lot of salaries, cars, gas and meetings.

Yeah, Adrian, that’s a really good point. Not that there’s necessarily a one-for-one correspondence here – “Let’s take $X million from NASA and spend it on anti-hunger agricultural stuff” – but Adrian is right that some dent could be made with perhaps less money than I was willing to admit. This is from Dec. 12 Science, a review article about the global food situation suggesting policy approaches to deal with it:

Crop yield growth has slowed in much of the world because of declining investments in agricultural research, irrigation, and rural infrastructure and increasing water scarcity. New challenges to food security are posed by climate change and the morbidity and mortality of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS). Many studies predict that world food supply will not be adversely affected by moderate climate change, by assuming farmers will take adequate steps to adjust to climate change and that additional CO2 will increase yields. However, many developing countries are likely to fare badly. In warmer or tropical environments, climate change may result in more intense rainfall events between prolonged dry periods, as well as reduced or more variable water resources for irrigation. Such conditions may promote pests and disease on crops and livestock, as well as soil erosion and desertification.[1]

My premise about the benefit of research money for global food issues looks wrong from this perspective:

In addition to being a primary source of crop and livestock improvement, investment in agricultural research has high economic rates of return . Three major yield-enhancing strategies include research to increase the harvest index, plant biomass, and stress tolerance (particularly drought resistance). For example, the hybrid "New Rice for Africa," which was bred to grow in the uplands of West Africa, produces more than 50% more grain than current varieties when cultivated in traditional rainfed systems without fertilizer. Moreover, this variety matures 30 to 50 days earlier than current varieties and has enhanced disease and drought tolerance. In addition to conventional breeding, recent developments in nonconventional breeding, such as marker-assisted selection and cell and tissue culture techniques, could be employed for crops in developing countries, even if these countries stop short of transgenic breeding. To date, however, application of molecular biotechnology has been mostly limited to a small number of traits of interest to commercial farmers, mainly developed by a few global life science companies.

Although much of the science and many of the tools and intermediate products of biotechnology are transferable to solve high-priority problems in the tropics and subtropics, it is generally agreed that the private sector will not invest sufficiently to make the needed adaptations in these regions with limited market potential. Consequently, the public sector will have to play a key role, much of it by accessing proprietary tools and products from the private sector.

One big thing that seems to work is the simple-sounding solution of helping folk build good roads:

Government expenditure on roads is the most important factor in poverty alleviation in rural areas of India and China, because it leads to new employment opportunities, higher wages, and increased productivity.

But there’s good reason to think that having us waltz in with our cool new food-growin’ technology may not be the most effective approach:

Smallholder farmers in the tropics have skills and social networks that give us cause for optimism for future soil quality and food security. Many are managing their soils sustainably and productively. Although they tend to be limited in labor resources (i.e., have low "human capital"), they compensate in forms of collective action and networking (i.e., "social capital"). This means that they adapt technologies to their local needs (using indigenous knowledge and innovation) and avoid labor-demanding and expensive practices. Interventions that use community-based approaches that empower farmers to manage their own situation therefore hold the greatest promise for maintaining soil quality and ensuring food security.[2]

So there’s something to be said, apparently, for listening to the folks we’re trying to help.

1. Rosegrant, M.W. and S.A. Cline, Global Food Security: Challenges and Policies. Science, 2003. 302(5652): p. 1917-1919.

2. Stocking, M.A., Tropical Soils and Food Security: The Next 50 Years. Science, 2003. 302(5649): p. 1356-1359.

An astute reader, who I very much respect, called me out on the "why Mars" question.

His question: "why this, over feeding the hungry, curing cancer, or stopping AIDS?"

First, if his argument is to have any merit, it has to apply to all basic science. Astronomy, geology, archaeology, paleontology, etc., all have the same lack of immediate practical import that makes them vulnerable to this argument. Mars is only the most visible precisely because it is so noticeable, which is to say, because it is so cool. But we do them all for the same reason, to use our treasure to satisfy our curiosity. (For that matter, his argument is easily extended to funding of the arts, which puts him on a slippery slope that he might not want to start down.)

I'll split feeding the hungry from the other two, because it's not clear that rearranging federal research spending has anything to do with solving the problem of hunger. The entire cost of the Mars missions, $820 million, is chump change aganst the hunger problem. As for research into cancer and AIDS, the effective doubling of the NIH budget over the last five years has left us with research funding that is essentially maxed out. Pumping more money into those endeavors has reached the saturation point. AIDS and cancer need time and smarts right now. Those research communities are pretty well funded. (There's what I think is a dangerous diversion going on right now in infectious disease research as we demand "homeland security", but that's a separate question.)

To say we're wasting the money because we're giving it, as Verbal says, to "a dysfunctional, wasteful organization" ignores the complexity of NASA. I would agree if he were to describe the human spaceflight program that way, but the robotic satellites have been hugely successful at a tiny fraction of the cost. The entire Mars missions, the both of them, full life cycle costs, are of order about the same price as a single shuttle flight these days. Well, come to think of it, the shuttle isn't flying these days, which makes the per-flight cost infinite, but before last year's deadly boo-boo, that's about what they were running. While the humans in space thing is a continuing disaster, bureaucratically as well as in terms of the body count, I think the NASA folks sending up satellites and robots to do science are doing things pretty damn well.

There's an argument to be made, on which Verbal and I might agree, that within the basic research budget of the federal government, maybe Mars probes are not the most cost-effective of basic science tools. That's tougher, but in judging the benefits we get, looking at the grinding load on JPL's web servers suggests some important public desire is being satisfied here.

There's also a separate argument Verbal hints at but doesn't go to, which is the amount of federal research money spent on military technology. Defense R&D is larger than the non-defense stuff we're talking about here, and is probably worth pulling into this discussion.

So Verbal, if you're arguing that we should not fund basic research, and spend money on health research instead, I'd say we already we've reached a level of significantly diminishing returns. If you say we should not fund basic research, and fund hunger instead, I'd say we'd blow our wad in a week, end up with no basic science and make nary a dent in the hunger problem.

But if you wanna just shift stuff around within the basic research portfolio, I know some archaeologists who would be ecstatic. They pretty much just need gas money and the cost of a new trowel, and $820 million buys a lot of those.

(The AAAS has a helpful compendium of federal research spending data that illuminates these issues.)

I don't have a lot of patience, frankly, with the "Why Mars" question. If someone doesn't get it when you say, "because it's cool", then there's little hope for a deeper conversation.

"Because it's cool" isn't really the complete answer, of course, just a shorthand for the richness of of the human experience of gathering new knowledge, but if people don't get the "cool" part, they're probably not going to get the deeper issue of the centrality of acquisition of knowledge to the human experience.

I'm reminded of this by friend Jim, who passed along a link to Oliver Morton's crack at this. I didn't know Morton's work before, but now I'm a fan. It's a long version of something Morton did for Newsweek on the question, and it nicely encapsulates the curiosity that drives the Mars people:

This piece doesn't talk about life: it just talks about some of the reasons why Mars fascinated people more than most other things in the sky. So it's an indirect answer to so-whatters: it explains why others find the subject interesting, but doesn't try to justify that interest.

The piece is great, and Morton gets huge bonus points for a wonderfully turned Garbo/Lucille Ball metaphor. Go read it.

"The first time I got drunk was on Southern Comfort."

Pause.

"My date lost her wig."

With winter set in, I've been riding some of my miles in the gym on a stationary bike, and I'm still trying to settle in on the best way to do it. Outdoors, riding is play. Indoors is a little uncertain, but must not become work.

They've got TV's in the gym - usually one on CNN and the other on one of the network morning shows - and a tuner thingie that let's you listen to the TV's sound on an FM radio. So I've tried CNN. And I've tried NPR, though the reception inside the building is pretty poor. But there's something about the distraction of words in my ear that isn't quite working.

So today I took my CD player and listened to Hector Berlioz's "Harold in Italy". It's a piece he wrote after a trip wandering the mountainous Abruzzi, and I settled in and closed my eyes and let Hector be my guide as my friends and I rode sometimes hard and fast, sometimes at leisure, through these long winding valleys, past old villages to the base of these spectacular alpine climbs, then up.

The joke in cycling is that we all hear Phil Liggett in our head, doing the blow-by-bow commentary on our town line sprints or as we switchback up a difficult hill. But the wordless play-by-play of Belioz worked a charm.

The final movement - the Orgy of the Brigands - is a frenzy, and I was hammering up through steep woods, alone by this time on the steep climb, breaking out of the trees above timberline onto a false flat near the finish line, then steep again, and I looked down at my heart monitor. I was pegged.

In my mind's eye I won the stage, zipping up the jersey for the finish line. It was a memorable ride. I'll have to try that again.

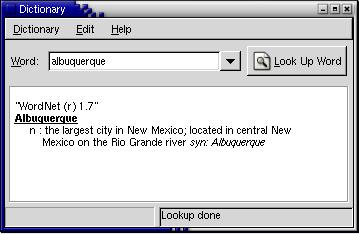

I just noticed an accidental joke I left in the GNOME dictionary docs.

To personalize the screenshot, I took an image of the dictionary looking up the definition of Albuquerque. It's been this way through several generations of GNOME releases:

This evening when I was checking docs for the 2.6 release I noticed what the search engine had returned:

Albuquerque

n : the largest city in New Mexico; located in central New Mexico on the Rio Grande river

Rio Grande river would be, uh, redundant. Like Sierra Nevada mountains or La Bajada hill.

Garnome built while I was at a lovely party last night. Included is the new Yelp (2.5.2) magic done by Shaun, magic that makes help display with great speed and alacrity, even the big ol' Gnumeric docs.

A team of Russian archaeologists has found a site in far northern Siberia that’s all kinds of interesting.

For starters, there’s the age. Radiocarbon dating puts the age at about 30,000 years old. That’s Pleistocene, ice age times. That’s the oldest human occupations north of the Arctic Circle yet found. This is key, because for the first Americans to get here, they had to go up and across the Bering Strait, which is up hard against the Arctic Circle. Before this, the first solid evidence of folks making up there was half that age.

But since this is a story about how folks first got from Asia to the Americas, the second bit is even more interesting. The archaeologists found a worked horn of a wooly rhinoceros that they say “bears a striking resemblance to Clovis foreshafts from North America”. Clovis culture is one of the first in North America, soon after the ice age slipped off. There’s a lot of arm-waving in archaeology, but this is arm-waving of a pretty interesting variety. This is an inference that those poor frozen sods in northern Siberia can be linked to Clovis culture.

New Scientist has a story, and the original paper is in Science (subscription required I think).

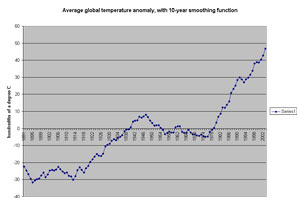

The Goddard Institute for Space Study has its December 2003 global climate data posted, and it shows 2003 as the third warmest in the century-plus of data they've got:

That's a 10-year rolling average to smooth out the noise in the data. You can see what Karoly et. al. suggest is a natural warming trend for the first half of the 20th century, and our greenhouse handiwork for the more recent half century.

The full GISS data set is here if you want to pull it down and play with it yourself.

The Missouri legislature will consider a bill this session requiring "equal treatment of science instruction regarding evolution and intelligent design".

Talk about muddy thinking. Try this

"Hypothesis", a scientific theory reflecting a minority of scientific opinion which may lack acceptance because it is a new idea, contains faulty logic, lacks supporting data, has significant amounts of conflicting data, or is philosophically unpopular.

The bill's list of definitions for some reason singles out "Extrapolated radiometric data" for special treatment, suggesting a young-Earth creationist hand on or near the tiller, which is almost surely the kiss of death for these guys.

I've been reading a lot of climate science lately, partly for the newspaper (see especially this piece on the warm 2003, which I've mentioned before) and partly for the book.

But even though I delved into the controversies a bit in my ABQJournal piece, I've largely stayed away from the hurly burly of the debate between climate scientists and the skeptics on the question of human-induced global climate change. The whole argument seems so talk radio that I just don't have much stomach for it.

But I poked my story at David Appell, and he blogged it. And the talk radio stuff began. It's been kinda fun, actually, mixing it up. I hope I haven't soiled myself too much in the process. After all, one owns ones posts.

The new stove arrived yesterday. The old stove was one of those hideous cheap white things that's always the cheapest thing on the showroom floor. We inherited it with the house when we bought it.

The new one is a thing of beauty.

That's my first omelette cooking on the new stove. It has spinach and broccoli in it.

Is there some sort of postmodern irony associated with the fact that I blogged the omelette before I finished eating it?

Edd Dumbill picking through proposal presentations for XML Europe 2004 has an interestingly empirical look at the XML Zeitgeist. Most interesting to me is his observation that government is going XML in a big way.

We aren't so smart and innovative as we think. From the Economist:

Where do you go when you want to know the latest business news, follow commodity prices, keep up with political gossip, find out what others think of a new book, or stay abreast of the latest scientific and technological developments? Today, the answer is obvious: you log on to the internet. Three centuries ago, the answer was just as easy: you went to a coffee-house. There, for the price of a cup of coffee, you could read the latest pamphlets, catch up on news and gossip, attend scientific lectures, strike business deals, or chat with like-minded people about literature or politics.The coffee-houses that sprang up across Europe, starting around 1650, functioned as information exchanges for writers, politicians, businessmen and scientists. Like today's websites, weblogs and discussion boards, coffee-houses were lively and often unreliable sources of information that typically specialised in a particular topic or political viewpoint. They were outlets for a stream of newsletters, pamphlets, advertising free-sheets and broadsides. Depending on the interests of their customers, some coffee-houses displayed commodity prices, share prices and shipping lists, whereas others provided foreign newsletters filled with coffee-house gossip from abroad.

(From Smart Mobs.)

For Dave: (Yeah, right, like he hasn't already seen this....)

New USA Today poll has Dean and Clark in a statistical dead heat.

Interesting reading the last couple of days on the British colonists at Roanoke and Jamestown, two groups who arrived on our shores in the late 1500 and early 1600s and were generally thought to have rather bungled things.[1]

The Roanoke settlers landed in 1587. When the resupply ship arrived four years later, the settlers had vanished. The called them “the lost colony”, and wrote off their deadly misadventure “to poor planning and inadequate supplies,” as deMenocal put it.

Perhaps paleoclimate ought to be added to the historians’ tool kit. When David Stahle and his colleagues several years ago put together a detailed tree ring chronology of the region’s historic climate, they found that the poor bastards had landed at the start of the driest three-year stretch in something like 700 years.

A second group landed in Jamestown in 1607. The Stahle data shows 1606 to 1612 was the other driest stretch in that 700–year period. “The settlers also suffered greatly,” as deMenocal says.

This doesn’t fit into my usual drought Cassandra theme, in which human societies overdo it during wet times, expanding beyond their means, and then get screwed when it dries out. But it’s an important example of the drought story.

1. deMenocal, P.B., Cultural Responses to Climate Change During the Late Holocene. Science, 2001. 292(5517): p. 667-673.

David Mason had an interesting observation about the New York Times' observation regarding the Clark campaign's "getting legs":

It reminds me of the feed they get from Wall Street every day about why investors bought or sold... its all best guesses at some sort of collective feeling.

I think about that as I watch the BBC news' business brief every evening on telly. The market is up X percent on news that blahpositive. Had the market been down that day, they would have looked around for blahnegative, which one can certainly find on any given day, to explain the downness. Some days the nexus is real, but often it's classic post hoc reasoning, carried out nearly every day, in full public view, by otherwise intelligent people, in an attempt to explain that which may very well be random.

Not to imply that all your hard work is resulting in some random swing, Dave. My interpretation is that the Clark campaign's great legs are a result of Dave's hard work.

I had occasion to use Bob Stayton's fine docbook xsl guide again this evening (had to reinstall fop processing tool chain to make pdf's) and was reminded anew of the amazing wealth of great resources freely shared out there.

At this time of the making of resolutions, let us remember the words of Samuel Pepys, who was smart enough on this day in 1664 to realize he was over-promising:

At my office til 12 at night, making my solemn vowes for the next year, which I trust in the Lord I shall keep. But I fear I have a little too severely bound myself in some things and in too many, for I fear I may forget some.

Methinks Pepys could have benefitted from a Palm. So home and to bed....

It was a little thing, but I finally some color coding to make the libxml API docs a bit more readable. DV's new docs build system has proven more robust and easier to work with than the old way it was done, but we lost color coding that helped break up the page and improve readability.

I haven't been doing much free software work lately, but what time I've had I've been spending on the libxml/libxslt docs. With Shaun at the helm, the GNOME docs system seems totally under control, and doesn't need any of my attention. I'll have to spend a bit of time there as the 2.6 release gets closer, but I feel so free not having to spend a lot of time on CVS build chores just to see where things stand. They stand fine.

Let us not forget that a hummer is, first and foremost, a bird.

In trying to understand the solution to the problem of the commons, the fisheries off the coast of Maine offer a tale both cautionary and instructive.

The “tragedy of the commons” is exemplified by the community pasture. The community as a whole benefits if grazing is restricted, so there is enough fodder for all of our cows. But if any one person defects and grazes an extra cow, he or she enjoys a singular disproportionate benefit, while the suffering is spread among all. This is the tragedy of the commons.

In the village this is most often dealt with by the fact that we all live in the same neighborhood, and we glare darkly at and ostracize the people who cheat. That is a time-tested and well developed strategy. We all understand the collective value of our pasture, and if we all have history in a place, and knowledge of its workings, this tends to work well.

Imagine the globe as the commons, however, where the benefit occurs in one place among one group of people, while the tragedy is spread wide. Think greenhouse climate change, where the benefit is disproportionately enjoyed by the industrialized world, while the people who live on low-lying islands stand to be screwed. Their glaring at us has not seemed to change our behavior.

Which is where the Maine fisheries example comes in. In their piece “The Struggle to Govern the Commons”[1], Thomas Dietz and his colleagues wander through a litany of examples, in which both top-down, governmentally imposed solutions for the management of the commons have been suggested, as well as those applied from the bottom up. The fish catch, managed by a governmental top-down approach, has largely collapse. The lobster catch, in comparison, has flourished, as the lobstermen themselves worked together to impose the necessary institutions to ensure that the commons can be sustained.

Inshore fisheries are similarly degraded where they are open access or governed by top-down national regimes, leaving local and regional officials and users with insufficient autonomy and understanding to design effective institutions. For example, the degraded inshore ground fishery in Maine is governed by top-down rules based on models that were not credible among users. As a result, compliance has been relatively low and there has been strong resistance to strengthening existing restrictions. This is in marked contrast to the Maine lobster fishery, which has been governed by formal and informal user institutions that have strongly influenced state-level rules that restrict fishing. The result has been credible rules with very high levels of compliance. A comparison of the landings of ground fish and lobster since 1980 is shown in. The rules and high levels of compliance related to lobster appear to have prevented the destruction of this fishery.

Hard to imagine how this insight might be applied to greenhouse gas emissions, but it does suggest that part of the framework required is an empowerment of the local. We know best how our own pastures work.

1. Dietz, T., E. Ostrom, and P.C. Stern, The Struggle to Govern the Commons. Science, 2003. 302(5652): p. 1907-1912.

Caves are other-wordly in terms both aesthetic and scientific. The aesthetics are obvious, but the science is becoming increasingly important, as biologists study the weird single-celled critters that live beneath the Earth's surface. Stephen Jay Gould once famously observed that the total biomass of single-celled organisms living in the Earth beneath a cow pasture is likely larger than that living in and above it. That makes all underground organisms important, but cave critters and other deep-rock organisms are especially so, because they have evolved entirely different metabolisms, gobbling up their dinner in completely different ways than the bits of life up here with which we are more familiar.

For that reason this cave is exceptional, undisturbed by human visitors until now:

While the snowy river of calcite may be the cave's marquee attraction— "the eye candy," Boston called it— much of the scientific interest is focused on an unassuming black dusty crud stuck to the ceiling.The crud, which Boston described as a sort of black mud crust, seemed at first to be an annoyance as the cavers struggled to keep from disturbing it and contaminating the pristine calcite.

But Boston, a biologist who specializes in the unusual organisms that grow in caves, found that the black crud was really a byproduct of single-celled organisms living on the walls and ceiling of Snowy River.

The microbiology of caves may be invisible, but it is vitally important to the science to be done there, Corcoran said.

And while we're bombing away at Google, it's a travesty that Phil Plait's moon landing page isn't ranked higher on Google. I think we should all link to it as well, though that's a tougher sell.

And as an aside, isn't it sad than nine out of the first ten hits for "moon landing" on Google are about the question of wether or not it was a hoax? Wouldn't it be great if when you typed "moon landing" you actually got something about the moon landing?

I think more people should like to Phil Plait's Planet X site, so that when you type "Planet X" into Google you get his vastly entertaining take listed above all the pseudo-scientific dreck.

My in-box doth overflow with the mail of Luis, as he wades through the thickets of bugzilla with Excalibur raised on high.

It's a wild and improvised thing, back to the roots, like John on rooftop:

"On behalf of the group I hope we passed the audition."

You go, guy!

On local public radio this morning (I was listening on headphones at the gym), literature professor Hugh Witemeyer talking about why D.H. Lawrence, a Brit, kept returning to northern New Mexico during his itiinerant life. Lawrence, Witemeyer said, was drawn to the "wild and improvised life of the American West". Even when you scrape away years of encrustations of Western mythos, there's something to that.

Witemeyer also said Lawrence loved to make his own furniture.

Imagine for a moment having a factory in your neighborhood that spews untreated effluent out its boilers' smokestacks, that some evenings you couldn't go outside for ten minutes without an asthma attack and clothes that stink.

Took the dog for a run Tuesday evening and didn't last but 10 minutes. My sweatshirt smelled of fireplace smoke, and I needed a slug on my asthma inhaler.

Another interesting commentary on risk perception, and the way our attitudes color that which we accept and that which we do not.