The Colorado River has dangerous currents. Moab, March 2022, photo by John Fleck

The most interesting news at this week’s University of Utah Stegner Symposium on the Colorado River Compact, past and future may be the news that we didn’t hear.

It was an amazing gathering, bringing together pointy headed academics like me with most of the basin management leadership team from tribes, state and local agencies, and the federal government. The crisis situation on the river made for some pointed conversations.

The news we did hear was stark:

- Colorado River Basin water users are currently consuming 14-15 million acre feet of water from a river that for the 21st century has averaged 12.3 million acre feet. Several water users suggested a need to be ready for that to continue to drop – 11maf? 9?

- Reclamation is scrambling to figure out how to safely move water through Glen Canyon Dam as Lake Powell dips below the safety threshold elevation of 3,525 feet above sea level, creeping toward “minimum power pool” – lowest since filling in the 1960s.

- Summer drying is making it harder for snowpack the following winter to make it to headwaters rivers.

- Declining river flows have us staring down a fundamental conflict, rooted in the century-old Colorado River Compact, about how much water upstream users are required to pass downstream past Glen Canyon Dam each year.

- Unresolved Native American water rights – some rights that exist on paper but aren’t being used, some not yet even quantified – have us on a collision course with fundamental legal and moral questions about equity as non-Indian users risk crashing the system while Native Communities have not yet had the chance to use water to which they have long been entitleld.

The news we didn’t hear – Las Vegas is not at risk of losing its water supply

Here’s what we didn’t hear: Las Vegas, Nevada, is not at risk of losing its water supply as Lake Mead’s levels drop toward Vegas’s intake pipes.

Was a time when the Las Vegas intake system was vulnerable as Lake Mead’s elevation dropped toward elevation 1,050. But years of planning and an expenditure of some $1.5b have the Southern Nevada community equipped with new intakes deeper in the reservoir, and a new pumping plant that is now scheduled to be flipped on for the first time later this spring as Lake Mead’s elevations drop toward elevation 1,060.

Turning on those pumps, designed to keep the water flowing to Las Vegas at the sort of elevations we’re now seeing, is a huge milestone, reflecting a community that took low probability/high consequence risk seriously and invested heavily in mitigation.

The low probability event is happening, the high consequences are not.

With Reclamation’s current “most probable” forecast showing Mead headed toward 1,035 in 2023, with a clear possibility of dropping into the 1,020s over the next 18 months, it’s fascinating to think about what the basin conversation would be like right now if the Southern Nevada Water Authority hadn’t built its “third straw”.

A few notes below on discussions that attracted my attention over the two-plus days of symposium sessions and the critical conversations in hallways, at dinners, and in hotel bars.

The integrity of Glen Canyon Dam

Assistant Secretary Tanya Trujillo was blunt about the risks as Lake Powell continues to drop. Under normal operating conditions, water is released through penstocks that drive turbines to generate electricity. But somewhere around elevation 3,490 (or maybe higher?), that becomes infeasible, first because of the risk to the turbines if air gets entrained in the inflows and second because at some point it’s physically impossible to get water out throught that door.

At that point, Reclamation is left with Glen Canyon Dam’s low elevation bypass tubes. Their use poses, in Tanya’s words, many operational uncertainties. Aside from testing and early filling days when the dam was built in the 1960s, they’ve only been used briefly during flooding in the 1980s, and during the relatively short-term high-flow experiments as part of the Glen Canyon Dam LTEMP.

Tanya continued to emphasize Reclamation’s statutory obligation to protect the integrity of the dam, something she also did in her public remarks at the December CRWUA meeting – the Colorado River Water Users Association. She said Reclamation may need to reduce annual flows from Glen Canyon Dam to protect the infrastructure.

That’s a big deal. In hallway conversations and side meetings, there was apparently significant conversation among state and federal officials about how all that might happen.

How small a Colorado River should we prepare for? 11maf? 9maf?

Southern Nevada Water Authority’s John Entsminger described how his agency’s long run planning includes a worst-case “what if” of an 11 million acre foot river. Recall that it’s been a 12.3maf river in the 21st century, which has been enough to drain the reservoirs. This would be worse. At 11 maf, Entsminger said, his agency’s modeling shows Mead bumping round 900 feet in elevation, while Powell is basically empty.

“The future of the Colorado River is pain,” Entsminger said. “Anyone who tells you anything different is selling something.”

Andy Mueller, from western Colorado’s Colorado River Water Conservation District saw Entsminger’s 11maf bet and raised (lowered?) him another 2 million acre feet, saying we need a plan in place to deal with the possibility of a 9 million acre foot Colorado River.

You shouldn’t see this as a disagreement between Andy and John. You should see this as a disagreement between the two of them and a bunch of other people in the basin. Last year’s Getches-Wilkinson Center conference in Boulder, for example, included a noteworthy exchange between Entsminger and New Mexico’s then-State Engineer John D’Antonio in which Entsmber suggested the need to prepare for an 11 million acre foot river and D’Antonio’s suggest that 13-14 maf is a more realistic planning baseline.

Consider what we might do with an 11 million acre foot river (never mind 9!). This is a world, under current operating rules, with likely cutbacks in the Upper Basin, a frequently dry Central Arizona Project canal, and difficult contestation over what the river’s operating rules really mean in a world far different from the one the Compact’s drafters thought they were in a century ago.

A quip from Arizona Tom Buschatzke suggests how hard these conversastions will be. “I won’t say I agree to 11,” Tom said in one of the many moments of remarkable frankness we saw over the two days of the symposium, “or I might get arrested when I get off the plane in Phoenix.”

Equities – tribal water

It is noteworthy that the symposium, one of the most important events during this year’s Colorado River Compact centennial, was co-sponsored by the Water and Tribes Intiative, an effort to expand the basin’s water management discourse.

The impact on our First People of our nation’s colonial history is profound. How to come to terms, in the area of water management, with that impact becomes an increasingly urgent question as the river shrinks. We have tribes with:

- legal rights to water now being put to use

- legal rights to water on paper that are not yet being put to wet water use

- unquantified rights

(see here from the Water and Tribes Initiative for more details)

We heard lots of positive discussion at the symposium about the recognition of this question, with tribal leaders (most notably Daryl Vigil from Jicarilla in New Mexico) and their representatives (especially Margaret Vick and Jay Weiner, two of the most prominent tribal attorneys, who play crucial briding roles between tribes and the water management law and policy plumbing). The question is how that talk translates into substantive roles for the basin’s 30 tribal sovereigns.

One key thing to watch: We’ve seen tribes playing an increasingly important role in the use of their currently used apportionments in helping solve basin problems. Will the discussions expand to compensation to tribes for the forebearance of the use of water not currently being put to use?

The tribal equity questions are far broader, but this question of whether compensation for forebearance is on or off the table is a test worth watching.

Equities – Upper Basin

My pal and coauthor Eric Kuhn gave an entirely too short presentation (I know because he shared the draft white paper version of the background with a bunch of us before the meeting) on the Upper Basin-Lower Basin equity issues embedded in a Compact that seems to set fixed deliver obligations at Lee Ferry regardless of what the climate is doing.

That fixed obligation would seem to place most of the climate change burden on the Upper Basin – no matter how much the river shrinks, we have to send 7.5 million acre feet per year (or, depending on one’s interpretation of unresolved legal questions, 8.25 maf) downstream.

Conversations about relaxing that Lee Ferry delivery obligation will be among the most difficult in coming years, but Eric argues it’s the only way to resolve this fundamental equity problem embedded in the 1922 Colorado River Compact.

“We need to manage the river we have today,” he said, “not the one we thought we had a hundred years ago.”

What are we thinking about when we think about Colorado River water management?

In light of today’s dire situation on the Colorado River, it’s interesting to return to the basic conceptual structure of the “2007 Interim Guidelines” – the rulebook for today’s river management.

The heart of the “interim Guidelines”

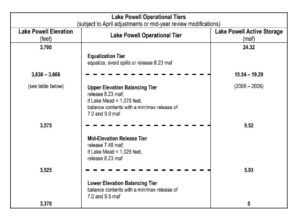

They include this crazy table. (There exist more graphically neato versions, but I think it’s worth going to the source.)

It defines a complex nested set of “if this then that” rules for determining how much water is released from Lake Powell each year. All the “ifs” refer to the elevation of Lake Powell and Lake Mead, the two giant reservoirs at the heart of the system. We are currently operating in the “Lower Elevation Balancing Tier”, which creates all kinds of crazy incentives. If the Upper Basin puts more water into Powell, some of that will end up being released to Mead under the rules. If the Lower Basin foregoes some water use to prop up Mead, under the rules that could trigger smaller releases from Powell.

This reflects a basic paradigm in Colorado River management – decisions made on the basis not of flow in the river but rather on the basis of water in the reservoirs.

This is because those reservoirs – the water they store, really – have been for nearly a century central to the project of building a hydraulic empire that is the West we all know and love. As one of my other pals and coauthors, Anne Castle, noted, they’ve been enormously valuable in helping with that task.

But that was then. Now?

“They don’t do us much good,” Anne said, “when they’re empty.”

This is why Southern Nevada’s construction of the third straw looks so smart in 2022. Down to a nearly empty Lake Mead, Las Vegas will still be able to get water.

The solution is clear, pull less water from the Colorado. How do we make up the difference? California desals there entire Colorado allocation and all the states share in the cost since we all will benefit.

The water management practice of damming a river to store water for future use is not a pathway to refilling reservoirs on an annual basis under declining natural river flows magnified by hotter droughts. Which begs the question–will the integrity of penstocks in a hydropower dam whose reservoir is unlikely to refill even matter?

Well John:

The Stegner Conference and past deliberations and pontifications must have presented all of the forever issues that the participant prognosticators could ever dream up. The result in the face of climate change is just more blah blah blah. The usefulness of these conferences, like diplomacy, keep all talking about the problems rather than recognizing that water availability is a zero sum game. Mother Nature just ain’t making any more of it and is most certainly making less of it.

Perhaps you can point me to the section of the Compact that says when the LBS get less than 7.5 million af at Lees Ferry the UBS are obligated to provide some of their 7.5 million af annually. Usually, if the UBS take 7.5 million af/y LBS get what is left over. Why should the LBS be rewarded for their profligacy. Let them build desal plants for their failure to plan seriously. Chinatown all over again. Real estate is through the roof as the well runs dry?

Bill

Where is the leadership? Have a conference and everyone goes home? Why isn’t there a full time working group? Why is UBS still stuck for 7.5 when there isn’t enough water? The Compact has to change. This all looks pretty childish to me.

First time I have heard about the bypass pipes. They are not shown in any cross sections I have seen. I wonder what the inlet elevation is.

Thanks for this great recap, John. I live in Utah, part of the Upper Basin States. I hear at the Colorado River Authority of Utah (CRAU) meetings that the Upper Basin should not have to bear the brunt of climate change and diminishing flows in the Colorado River – that it should be shared equally between the basins. Well, folks, talk to the ghosts of the Upper Basin State leaders who rolled the dice in the early 1920s and decided that instead of taking a firm amount of water, as the ‘apparently’ smarter Lower Basin States’ leaders did, that they would take only a percentage of what would be left after giving the Lower Basin States their required 7.5MAFY. They bet that there would be a surplus and the Upper Basin would benefit. Now we are stuck with that deal but are whining about it. Utah uses a lot of water. Lower Basin States are already giving through conservation and such including smart decisions made in Nevada (as John noted), which Utahns certainly have not been doing. I get so tired of Utahns’ whining! Live with what you were dealt. Put your big-boy and big-girl pants on and get with a real plan!

Hats off to the Southern Nevada Water Authority. Any individual or entity with any practical experience with water in the west, and knowledge of earth processes, would plan for the worst case and then implement it. Its just common sense.

SNWS has a 50 year plan for the area with an eye towards continuous population growth. What nobody realizes is when Mead drops too low, it won’t be able to generate enough power to deliver on contracts given. There aren’t enough solar fields out there that can replace the power generated by Hoover Dam. They may have a straw to get water for a short period of time after dead pool, but power will be a massive concern.

The plan they have also targets surrounding shallow aquifers, the muddy river reservation and their water as well as all the trading of water credits with CA and AZ. That last part is all well and good if there is water available. On the flip side, what are the long term consequences of continuing to grow?

Roger, there’s plenty of solar and wind available to replace the power from both Hoover Dam and the Glen Canyon Dam. With the past few decades of lower water levels they’ve already been generating less energy than they would have otherwise done.

At Hoover Dam they’ve installed different turbines that can work more efficiently with the lower water levels but at some point soon if there isn’t enough snowpack and rains they’re not going to be generating energy at one or both of those dams.

I thought it made a lot of sense to empty one or the other to prefer power generation but it seems that both are being set to empty instead of keeping one full. Evaporation would be less with surface area of both kept minimal but nobody wants to run them that low. That nobody wanting is costing perhaps a few hundreds of thousands of acre feet of water.

We shall see what happens next. Looks like a chance of a break this year if we can pick up a few more storms – the season isn’t over yet. Like farmers we hope for rains, but cannot know for sure we’ll get them until they happen.