While the historic June 15 low for Lake Mead has drawn headlines – “its lowest level on record since the reservoir was filled in the 1930” – we’re about to hit a similar milestone upstream at Lake Powell that has received less attention, but may in fact be more important.

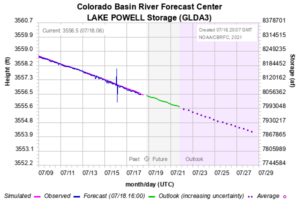

It was co-author Eric Kuhn who drew this to my attention – I hadn’t noticed. He notes that sometime around July 24 give or take our eyeballing of the Colorado Basin River Forecasting Center graph, Powell will cross elevation 3,555 feet above sea level. That was the previous post-filling low, on April 8, 2005. From there, you have to go all the way back to the summer of 1969, when Powell was first being filled, for the “last time Powell’s been this low” references.

I say “may be more important” because relative to Mead, Powell is where the Colorado River Basin’s chaos and uncertainty are most clear.

Users who get their water from Mead have a huge reservoir with a predictable inflow above it – the Upper Basin’s releases from Lake Powell. That means if you’re a water manager in Los Angeles or Phoenix or Las Vegas or Imperial, you have a clear picture of what to expect over the next several years. The expectations may be for a reduced supply, but you can operate with pretty clear expectations about what the reductions will look like, and least for the next few years.

Powell is where the real trouble shows up first. 3,555 is a loud and discomforting noise.

Yes, this is generally how the system operates, as I recall. When in operations at Boulder Canyon, I recall that Powell would see the larger fluctuation of inflow from either rainfall events or snowmelt, or both a rain-on-snow event. Releases downstream served to attenuate wild fluctuations at Mead, which occurred before Powell was built. Some of the pre-Powell fluctuation of inflow and in reservoir elevations would trigger small seismic events around Mead, as a result of loading from water weight.