A guest post by historian Sara Porterfield:

“May 24, 1869—The good people of Green River City turn out to see us start. We raise our little flag, push the boats from shore, and the swift current carries us down.”

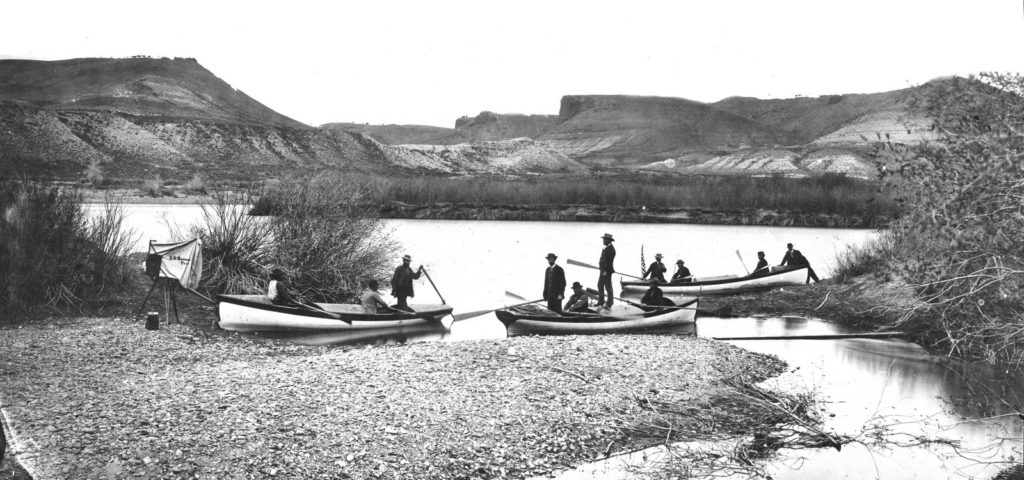

This photograph is of Powell’s 2nd expedition in 1871-2, but he squished both expeditions together in his published journals, so this is somewhat fitting.

Today marks the 150th anniversary of John Wesley Powell’s 1869 expedition down the Green and Colorado rivers from the town of Green River, Wyoming to the confluence of the Colorado and the Virgin on the downstream end of the Grand Canyon. The sesquicentennial of this journey of more than 900 miles into what Powell called “the Great Unknown” has, in the year leading up to today, garnered attention from water wonks, whitewater boaters, scholars, and casual observers, and it will undoubtedly continue to do so over the course of this year—and rightly so. Already, Powell’s journey has spawned op-eds, books, and replica journeys (albeit, undertaken with modern rubber boats rather than the ill-suited wooden boats Powell commissioned), all of which is unsurprising and even fitting given the larger-than-life status Powell has come to inhabit in the minds of conservationists, Western water stakeholders, and those of us who occasionally like to run the rapids of the Colorado River Basin.

Anniversaries—particularly one as significant as 150 years—provide a ready-made opportunity to celebrate and remember individuals, their actions, and their legacies. But in commemorating Powell, his expedition, and his contrarian vision of Western settlement that grew out of his firsthand experience in the Colorado Basin, we’ve missed an opportunity to reflect critically on the American response to and memory of Powell over the past century and a half. Rather than unquestioningly celebrating Powell and his legacy, this year gives us the chance to think about a couple of points:

- First, how are we telling Powell’s story now, and how have we told it in the past? Is it, and has it been, accurate and useful?

- Second, whose stories have we excluded, ignored, and forgotten about in the focus on Powell?

When we start to answer these questions, the sesquicentennial of Powell’s journey becomes an opportunity to explore new and different ways of thinking about the Colorado River and Western water.

I will be the last person to say that Powell wasn’t a deeply impressive person who provides us twenty-first-century dwellers ample fodder for celebration of his legacy. He planned, funded, staffed, and executed (on a shoestring budget) a months-long expedition into a region unknown to Euro-Americans. In perhaps his most oft-quoted passage, Powell captured this sense of looking past the edge of the known world: “We have an unknown distance yet to run, an unknown river to explore. What falls there are, we know not; what rocks beset the channel, we know not; what walls rise over the river, we know not. Ah, well! We may conjecture many things.” To make this feat even more impressive, Powell had only one arm. He was a disabled military veteran, having lost his right arm at the elbow after a Confederate minié ball shattered his wrist at the Battle of Shiloh.

Powell’s legacy may have been fairly well assured had he returned to teaching college courses on natural history upon his return from the Colorado, but he did not rest on his laurels. Instead, he became a bureaucrat in the nation’s capital, where he pushed back against the boosterism of his day that promoted the West as a limitless and idyllic Eden where “rain follows the plow” and settlers would find easy success. Based on his experience in the “Arid Region,” Powell advocated caution instead of a headlong rush to populate the West, arguing that the region couldn’t sustain the population boosters advertised because of its climate. This debate produced what is probably the single most recognizable image in Western water history—Powell’s map of Western states drawn by watershed—and cemented his legacy as a progressive thinker who understood the concept of environmental limits.

Yes, these are reasons to celebrate Powell. But remembering him in this way has created its own set of problems.

First is the celebration of Powell’s journey into the “unknown.” Unknown, one might ask, to whom? Certainly the Indigenous people of the region knew the river and its environs intimately—it was unknown only from a Euro-American perspective.

Second, focusing on Powell also creates an image of the nineteenth century Colorado River from the viewpoint of a white, male, colonial character, a perspective that has persisted throughout the twentieth century and is only beginning to change (haltingly) in the twenty-first.

Third, the mythic proportions Powell’s battle against the boosters has taken on makes it the origin story for a history of Western water defined by conflict—the un-usefulness of which I don’t have to explain if you’re reading John Fleck’s blog. Finally, because Powell provides such an epic and charismatic figure, his viewpoints and actions are too often misremembered, distorted, and molded to fit the present day. See my review of a recent book about Powell for further discussion of the problems of presentism and inaccuracy.

So what have we missed in focusing on Powell? He is, it must be said, yet another dead white guy who’s been lionized in the intervening 150 years. Whose stories have we ignored in retelling his over and over? At the top of my list are the stories of the Indigenous peoples of the Basin. Yes, Powell was also an ethnographer and worked to record tribal customs and language—but only because he thought it inevitable that they would die out in the face of Anglo advancement into the West. What would an Indigenous history of the Basin look like? In this vein, what about a women’s history of the Basin, or a history of race and water? Westerners, those of us involved in water, in particular, are storytellers. Let’s tell better, more accurate, and more helpful stories that can help welcome a more diverse range of stakeholders to the table (while acknowledging they’ve been present the whole time), and that can encourage a larger portion of the population to see themselves in the history of how the Colorado came to be what it is today.

To this end, my colleague Dr. Adrianne Kroepsch, at the Colorado School of Mines, and I have started a Google Doc to build a better, more diverse repository of sources for Colorado River Basin history. Please feel free to browse, add to, and share the document, available publicly at this link: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1P2Bcg-xzNi8GgmDuSdIZfPGM9CACJSyLGTEE7N7WKIs/edit?usp=sharing

The story of Powell being rescued by a pair of long underwear comes to mind. Field work has its shortcomings at times and we all have to improvise for the situation.

Great post Sara (and John!). This is important work you’re doing. It’s healthy for all of us to take a fresh look at history and ask questions about why we tell the stories we do. It doesn’t diminish the stories we have, but enlarges and enriches them.

What would John Wesley Powell say now???

This post is amazing. Thank you.

White western water people in power ignore the natives and the massive amount of knowledge and tradition they have. Many tribes have a culture that makes water a treasure to be protected. They are ignored as are their lessons. The general public never know. Looking around at our recent past and our near future … It’s enough to leave me depressed.