High temperatures mean less water on the Colorado River

A warming climate is already reducing the flow in the Colorado River, and the future risk is large, with a worst case of the river’s flow being cut in half by the end of the century, according to a new study from a pair of the region’s leading researchers. While precipitation declines since the turn of the century have been modest, Brad Udall and Jonathan Overpeck found, a little less rain and snow have translated to a lot less water in the river:

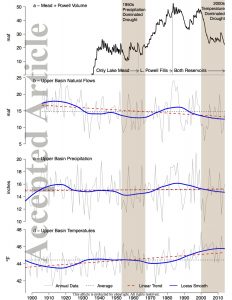

Between 2000 and 2014, annual Colorado River flows averaged 19% below the 1906-1999 average, the worst 15-year drought on record. At least one-sixth to one-half (average at one- third) of this loss is due to unprecedented temperatures (0.9°C above the 1906-99 average), confirming model-based analysis that continued warming will likely further reduce flows.

Their analysis suggests substantial risk going forward:

Recently published estimates of Colorado River flow sensitivity to temperature combined with a large number of recent climate model-based temperature projections indicate that continued business-as-usual warming will drive temperature-induced declines in river flow, conservatively -20% by mid-century and -35% by end–century, with support for losses exceeding -30% at mid-century and -55% at end-century.

While we have seen projections of the future impact of climate change on the Colorado for more than two decades, this study is important because it is one of the first to argue empirically that the change is already underway. (See also Woodhouse and colleagues last year, which I wrote about here.)

Key to the new paper’s argument is a comparison between the previous worst 15-year drought on the Colorado River, from 1953-1967, and the current one. As measured by precipitation, the ’50s were a lot drier than now. But the current drought, which began in 2000, is a lot drier in terms of river flow. The difference? It’s a lot warmer now than it was back then.

Such temperature-driven droughts have been termed ‘global-change type droughts’ and ‘hot drought’, with higher temperatures turning what would have been modest droughts into severe ones, and also increasing the odds of drought in any given year or period of years [Breshears et al., 2005; Overpeck, 2013]. Higher temperatures increase atmospheric moisture demand, evaporation from water bodies and soil, sublimation from snow, evapotranspiration (ET) from plants, and also increase the length of the growing season during which ET occurs.

The results are not a surprise. It seems like at every Colorado River conference I’ve attended over the last few years, either Overpeck or Udall have been on the agenda presenting preliminary “work in progress” results on this. Beyond the stark data, they’ve been making two points. The first is the need for much more serious adaptation measures to cope with the reality of having less water.

This means using less water.

The second, and more important point for the two researchers, has been the imperative to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to protect the future of the southwest’s Colorado River-using communities:

The only way to curb substantial risk of long term mean declines in Colorado River flow is thus to work towards aggressive reductions in the emissions of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

Pingback: Deadline Looms for New Water-Sharing Deal Between US and Mexico - WhoWhatWhy