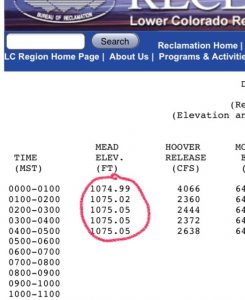

Apparently in celebration of this week’s official release date for my book Water is for Fighting Over: and Other Myths about Water in the West, Lake Mead overnight crept above the magic elevation level of 1,075 feet above sea level. That’s number attached in policy and, more importantly, the public mind to the notion of shortage on the Colorado River. At this point the elevation milestone is merely symbolic. The shortage policy, with mandatory cutbacks, only kicks in if the reservoir is below 1,075 on Jan. 1 of any given year. Mead typically rises between August and the end of the year, so there will be no shortage declaration at the end of the year.

Don’t get too excited about rising above 1,075. We’re still on track to set another one of those “lowest elevation since Lake Mead was filled” records yet again this month. The end-of-August record low is 1,078.31 which we set last year. And as Brett Walton noted this morning in Circle of Blue’s Federal Water Tap, there’s a greater than 50 percent chance of a below-1,075 shortage declaration in 2018.

As a science-policy communicator, I’m fascinated with the way “1,075” has become such a useful shorthand for a complex set of issues. The origin of its importance lies in the 2007 “Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and Coordinated Operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead”. The rules are complicated: every year in August, the Bureau of Reclamation runs its Colorado River Simulation System (CRSS) model, a dynamic simulation that takes current reservoir levels, projected demands and forecasts for the coming months, and estimates the elevation of Lake Mead the following Jan. 1. That estimate (and an accompanying one for Lake Powell, the big reservoir upstream) triggers a number of policy responses. If there’s a bunch of extra water in Lake Powell, we enter one of a couple of operating regimes under which what I’ve come to call “bonus water” can be released from Powell to prop up Lake Mead, a process intended to “equalize” the levels between the two reservoirs.

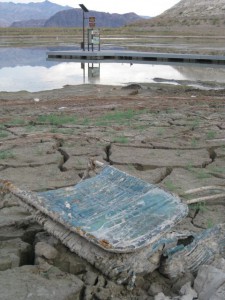

Boulder Harbor, Lake Mead, Oct. 18, 2010

If Mead is low, separate rules kick in which reduce the allocation of water to downstream users, mostly the states of Arizona and Nevada. The first threshold for “low” is 1,075, which would trigger a shortage declaration.

The intellectual exercise of trying to understand these rules (they’re quite complex) and more importantly the process of conflict and negotiation through which they came about laid a lot of the groundwork for my book. My argument, which grew as much as anything out of a long conservation in the spring of 2010 with John Entsminger, then chief counsel and now general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, is that the success or failure of water management in the Colorado River Basin hangs on the ability of a network of people, both formal and informal, who must simultaneous fight for their own states’ allocation of water from the river while at the same time realizing that we have to have negotiated deals in which everyone takes less water. From Chapter 10:

Somehow, the network’s members now had to come up with a new set of rules that could both balance reservoir levels in Mead and Powell, as well as provide some certainty for how shortages would be handled among the Lower Basin states if Lake Mead kept dropping.

It meant understanding one another’s positions, but it also meant honoring a shared goal—keeping their dispute out of court. “We knew where the disagreements were,” said Entsminger, “and the choice was litigate those disagreements or find a working solution.”

What’s fascinating now is the way “1,075” has rippled out from the core group of negotiators and a complex set of federal documents to become a symbolic stand-in for the deep issues confronting the Colorado River Basin. As I wrote six years ago when I first started working on the book, drought in the Colorado River Basin is such an abstraction. 1,075 has helped make it a bit more real.

With a new set of negotiations underway that are likely to lead to deeper water usage cuts, and sooner, it’s entirely possible that in the coming year 1,075 will become less relevant. Maybe 1,090 as a new threshold? But wherever we end up 1,075 has done great work in helping us grapple with the Colorado River Basin’s problems.

Letting 9 million acre-feet out of Lake Mead every year is based on flawed data. The 30 year agreement allows most of the water to flow to Califonia and out the Sea of Cortez in Mexico.A better solution would be to only allow 75% to 80% of the given year’s Colorado snow pack to be released from Lake Mead. California needs to fix its leaking water pipes, toilets, and faucets and what crops are grown. The state should also builds water de-salination plants along the coast line.