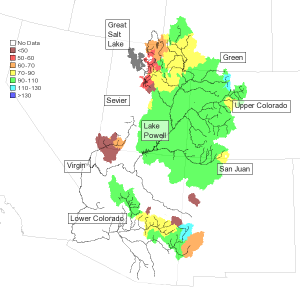

I suppose it’s a sign of the times on the Colorado River that a January forecast of 95 percent of average flow into Lake Powell counts as good news. Since green on the Colorado Basin River Forecast Center map runs from 90 to 110 percent, we get green. It’s only a little bit below average!

Last year, per the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s final numbers (pdf) was dismal:

The Colorado River total system storage experienced a net decline of 4.09 maf (5,040 mcm) in water year 2013. Reservoir storage in Lake Powell decreased during water year 2013 by 3.00 maf (3,700 mcm). Reservoir storage in Lake Mead decreased during water year 2013 by 0.773 maf (953 mcm). At the beginning of water year 2013 (October 1, 2012), Colorado River total system storage was 57 percent of capacity. As of September 30, 2013, total system storage was 50 percent of capacity.

The grim state of affairs on the Colorado River brought front page attention earlier this week from the New York Times which, as Jennifer Pitt pointed out yesterday, can’t hurt:

The article helped to elevate the reach and understanding of Western water issues, but for those of us in Colorado and other basin states, this reality is one we must face every day.

I mostly liked Michael Wines’ NYT piece. He went beyond the usual “there’s not enough water” teeth-gnashing to talk about some of the solution space, including examples of municipal and agricultural water conservation. That’s a step beyond what even some of the in-basin journalism (including some of my own, mea culpa) gives us. Given the way I’m currently lost in Colorado River minutia, it was instructive to see a pro come in from afar and nicely sum up the basics for an outside audience, and Wines was smart to pick up on some of solution space. Even some water nerds don’t fully grasp the importance of the whole “return flow” concept:

There may be ways to live with a permanently drier Colorado, but none of them are easy. Finding more water is possible — San Diego is already building a desalination plant on the Pacific shore — but there are too few sources to make a serious dent in a shortage.

That leaves conservation, a tack the lower-basin states already are pursuing. Arizona farmers reduce runoff, for example, by using laser technology to ensure that their fields are table flat. The state consumes essentially as much water today as in 1955, even as its population has grown nearly twelvefold.

Working to reduce water consumption by 20 percent per person from 2010 to 2020, Southern California’s Metropolitan Water District is recycling sewage effluent, giving away high-efficiency water nozzles and subsidizing items like artificial turf and zero-water urinals.

Southern Nevada’s water-saving measures are in some ways most impressive of all: Virtually all water used indoors, from home dishwashers to the toilets and bathtubs used by the 40 million tourists who visit Las Vegas each year, is treated and returned to Lake Mead.

But I agree with Pitt’s critique that Wines missed the river itself, which is an increasingly important part of the regional conversation about the basin’s future:

It is the lifeline of the American West. It is a river of legends, with awe-inspiring canyons that have for centuries seduced people to explore their depths. Citizens of the West and the rest of the globe alike love the Colorado River for the thrill of its rapids, the shade of its riverside forests that make for epic fishing, and the serene calm of a morning view from a houseboat on one of its large reservoirs.

Getting this piece right will have to be part of the grand bargain and cultural shift needed to cope with our water future.

With all the runoff in Colorado, aren’t there relatively inexpensive ways to get more water INTO Lake Mead?