On a quick weekend dash to Ogden earlier this month, I squeezed an hour out of my return trip to the Salt Lake City airport to make the drive out the causeway across the Great Salt Lake to Antelope Island.

When G.K. Gilbert, under the direction of John Wesley Powell, was trying to sort out the climate history of the region during the mid-19th century, he turned to the early Mormon herders for help. The Great Salt Lake was then a great climate integrator, a closed basin that rose during wet times and fell during dry – sometimes allowing access to Antelope Island, sometimes not. There were other similar sites, most notably the access to Stansbury Island. The herders kept track, and Gilbert was able to use their stories to generate a crude but usable “paleoclimate” record over the previous 30 years.

G.K. Gilbert’s Great Salt Lake level reconstruction, from the Report on the Lands of the Arid Region

I’ve always loved the story (I included it in my book), because Gilbert was so clever and because, if you look that drop in the lake’s level he identified beginning around 1855, he seems to have pretty much nailed the story that 21st century scientists now understand about that time period.

As far as I know, we have no rain gauge data from that time period around the Salt Lake, but tree ring records have been used to reconstruct what Richard Seager calls “the Civil War drought,” extending from the mid-1850s to the mid-1860s.

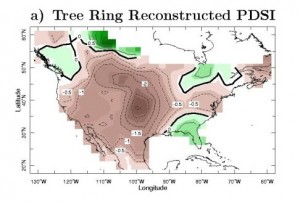

The drought was quite broad, as Seager’s map (based on tree ring data compiled by Ed Cook at LDEO) shows.

The culprit? La Niña. Seager’s group used the relatively sparse ocean temperature data reconstructions available, which are based on ship-board records, to drive climate models. They showed a persistent La Niña phase, and driven by that, the models did a nice job of reproducing the spatial nature of the drought as shown in the tree ring records.

And in Gilbert’s clever 19th century reconstruction as well. For a paleo nerd, worth a quick pilgrimage on the way to the airport.

(Seager’s group has a great web page summarizing their work on 19th century drought.)