Steve Hannon tells the dramatic story of what nearly happened to Glen Canyon Dam during the great El Niño year of 1983, when heavy winter snows, then rain on that snow, caused Lake Powell to rise rapidly and exposed problems in Glen Canyon Dam’s spillways:

The spillways had only operated for a few days when a slight rumbling and vibration began to be felt in the abutments and the dam itself. Close inspection of the jets emerging from the tunnel portals revealed some debris being ejected in the flow: chunks of concrete, sections of rebar, and, most disturbingly, what looked like pieces of sandstone, arced high above the river.

Yikes.

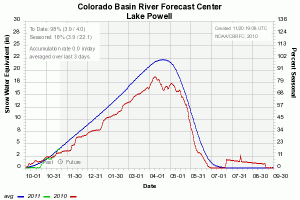

We appear to be in no danger of problems like that this year. Powell’s surface is currently about 80 feet below its 1983 peak. Eyeballing the record, I can’t see a year with anything close to an 80-foot rise in a single year. Still early in the season (about a quarter of the way between Oct. 1 and the average April snow pack peak), the numbers above Lake Powell are about exactly average.

As we speak, my friends in the mountains of Colorado, especially on the water-making west slope, are hunkered down under winter storm notices, waxing their skis. So expect bigger numbers by tomorrow.

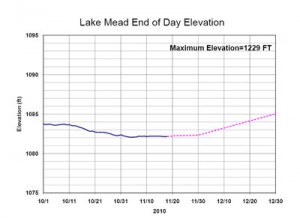

Downstream, Lake Mead is finally starting to rise again. Releases from Glen Canyon Dam upstream picked up Nov. 1, and Mead appears to have bottomed out for the year (and for a new post-filling record) at slightly above 1082 feet above sea level. The forecasts now call for a steady rise in Mead’s level through the winter, to perhaps 1091 before we begin draining it again next year to meet water needs in the lower basin.